So we shall let the reader answer this question for himself: who is the happier man, he who has braved the storm of life and lived or he who has stayed securely on shore and merely existed?

Hunter S. Thompson, The Proud Highway: Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman, 19551967

I had one shot to make it in lifenot in baseballin life. I was fighting for my survival.... So if this didnt work out, I dont know.... My life would be over.

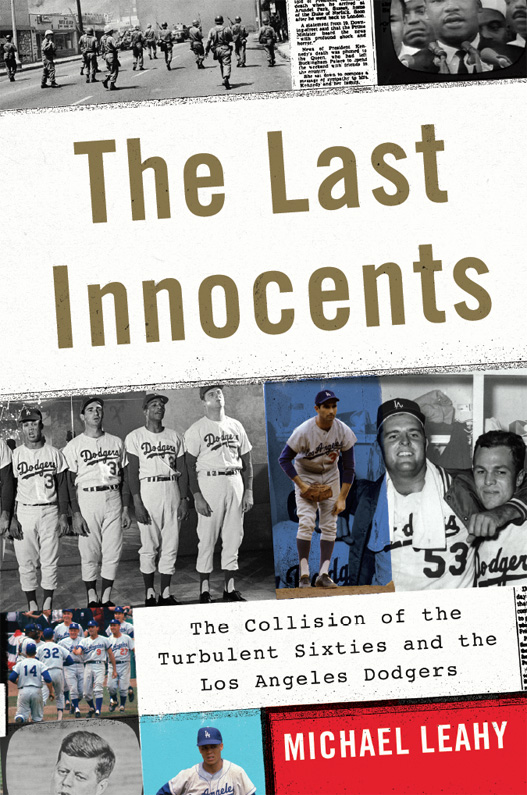

I t came to this one night in New York City, during the middle of the 1956 World Series between the Dodgers and Yankees. After arguing in a bar with a Yankees supporter about the merits of their two teams, a twenty-five-year-old Dodgers fan went home, returned with a rifle, and shot dead his antagonist, who happened to be a local police detective.

These things happened.

No other American sport at the midpoint of the twentieth century sparked such fervor, idolatry, rage, madness. No other game was as sectarian in the adoration and hatreds it instilled; in the way it divided cities and sometimes families; and in the speed with which its young, strapping idols, in some cases ambling into stardom straight out of cornfields and back alleys, became deities for one group of fans and demons for another. Ticker-tape parades lionized the games winners. Merciless ridicule rained down on vilified losers. The emotional well-being of ordinarily sensible men and women rose and fell with their teams. The agonizing faithful of entire street blocks sat on stoops listening to radio broadcasts during a pennant race.

There was nothing else on the planet quite like it.

And luck had much to do with the games good fortune.

The truth went unadmitted during its boom years, but baseball largely owed its supremacy over American professional team sports, and its hold on the American psyche, to having launched itself before its rivals. In the nineteenth century, the major leagues sprang from the starting gate alone. This propitious bit of timing counted for everything. The fledgling organization that in time would come to be known as the National Football League wouldnt be created until 1920; the enterprise eventually to be called the National Basketball Association wouldnt arrive until 1946. By then baseball had been Americas chief sporting passion for decades, boosted early by a bit of marketing genius. The sport had captivated romantics with a dream event whose transcendent namethe World Serieswould leave all competitors in its shadow for the first two-thirds of the twentieth century.

If anything, on the eve of the 1960s, that shadow seemed to be lengthening. The mania for the game presented the perfect breeding ground for new baseball gods to be born in the American West, the ideal moment for the arrival of the Los Angeles Dodgers. The 1950s had been baseballs most thrilling decade yet. The dynastic New York Yankees, as famous as any team in the world, stood as a symbol of American glamour and power. The National Leagues burgeoning racial diversity and new talent made its challenges to Yankee superiority more heart-stopping than ever. In 1955 Brooklyn finally bested the Yankees to win its first World Series. The following year the Series spawned magic, in the form of a no-hit perfect game, with Brooklyn as the victim. The feat came from an unlikely Everyman, the hard-throwing but erratic Don Larsen, who was king for a day while pitching for a Yankees squad that, in regularly making gods out of flawed mortals, reclaimed the Series championship and looked as though it might reign forever.

So hypnotic was the World Series that it had risen to be a somewhat illicit holiday. It took priority over many adults jobs and childrens schooling during the week or so that it lasted. Hordes of men and women sneaked away from workplaces all over the country to watch the nationally televised afternoon games. Taverns filled. Classrooms were suddenly missing a few children. Normally attentive students concealed transistor radios in notebooks, stealthily listening to the coast-to-coast broadcasts. Big-city pedestrians, away from their offices, paused for long stretches in front of appliance-store display cases, where brand-new televisions showed the games from start to finish.

The obsession led strategists of both major political parties during the presidential campaign of 1960 to realize the obvious: they wouldnt have the complete concentration of a significant bloc of voters until the great battle of early Octoberthe one pitting the imperious Yankees against the National League pennant-winning Pittsburgh Piratesfinally ended. There is a politicians rule of thumb, particularly hallowed by Democratic politicians, that no election campaign starts until the World Series is over, wrote Theodore H. White in 1961, in his renowned book on the 1960 campaign. Many Americans couldnt focus on the contest between John Kennedy and Richard Nixon until after Pirates second baseman Bill Mazeroski hit the winning home run in the bottom of the ninth inning of the decisive seventh game of the Series, giving Pittsburgh its first World Championship in thirty-five years.

By then, just to win a league pennant and reach the Series had become a cherished prize, nearly as big as winning the Series itself. Nine years earlier, with the sport at the zenith of its popularity, baseball presented fans with the most electrifying finish to any game in its history. With the Dodgers facing the Giants in the climactic contest of a three-game playoff for the 1951 National League pennant, Brooklyn led in the bottom of the ninth inning at the Polo Grounds, only to lose on a three-run homer off the bat of Giants third baseman Bobby Thomson against Dodger reliever Ralph Branca. The Giants euphoria was equaled in intensity only by Dodger despondency. Yet the game cloaked both the winner and loser with a glory and mystique that were portable when the two rivals bolted to the West together, seven years later. As always, baseball was the biggest victor.

This had implications for Los Angeles. The Dodgers, winners of the 1959 World Series in only their second year in the city, dominated the Southern California sports market, relegating the NFLs Los Angeles Rams to secondary status, along with the NBAs Los Angeles Lakers, a franchise that arrived in 1960 from Minneapolis. The two junior sports were still several years away from the gripping theater that would accompany the introduction of the Super Bowl, Monday Night Football, and national telecasts of the NBA Finals. Other than a riveting championship game won in sudden-death overtime by the Baltimore Colts over the New York Giants in 1958, the NFL could point to nothing, in the broad publics view, that matched the drama of an average World Series. Nor had the attention the press paid to the accomplishments of professional football and basketballs stars come close to rivaling the adoration heaped on the milestone achievements of baseballs legends. The most famous record in American sportsBabe Ruths sixty home runs in 1927had been showered that year with a reverence equaled in the country only by the awe for Charles Lindberghs Atlantic crossing.

Bereft of the glittering athletic stages necessary for supreme drama, neither professional football nor basketball had produced cultural divinities like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio and Ted Williams, Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella, Henry Aaron and Stan Musial, Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays, or, in 1961, Roger Maris, who would break Ruths single-season home run record that autumn, after surpassing Mantle during a summer duel that transfixed America.