In order of appearance, as they were then:

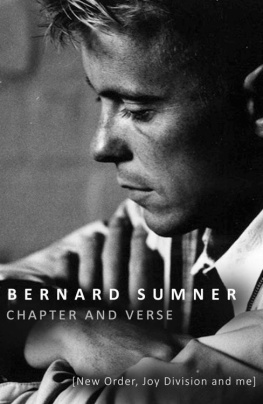

Bernard Sumner: Joy Division

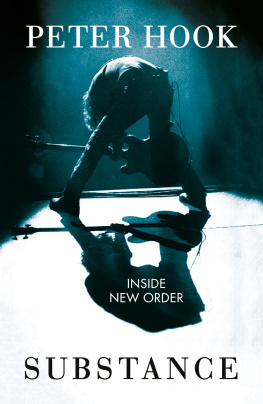

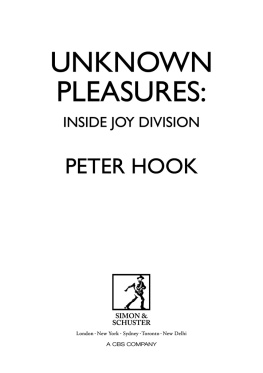

Peter Hook: Joy Division

Stephen Morris: Joy Division

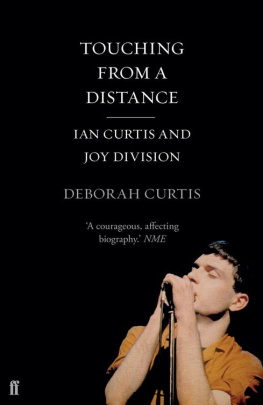

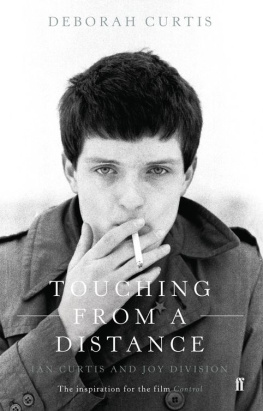

Deborah Curtis: wife of Ian Curtis; witness

Tony Wilson: presenter, Granada Television; Factory co-founder

C. P. Lee: Alberto y Lost Trios Paranoias

Peter Saville: Factory co-founder and art director

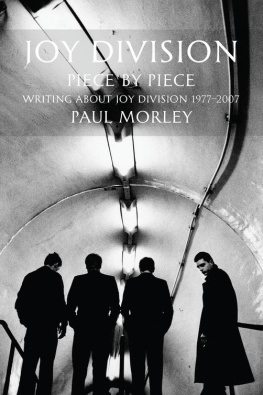

Paul Morley: writer, New Musical Express

Liz Naylor: writer, No City Fun

Terry Mason: Joy Division road manager

Iain Gray: witness

Ian Curtis: Joy Division

Mark Reeder: Factory Deutschland

Michael Butterworth: bookseller

Martin Hannett: producer and director, Factory Records

Pete Shelley: Buzzcocks

Alan Hempsall: Crispy Ambulance

Richard Boon: Buzzcocks manager

Kevin Cummins: photographer

Jeremy Kerr: A Certain Ratio

Bob Dickinson: writer, New Manchester Review

Richard Searling: Grapevine Records, Wigan Casino DJ

Rob Gretton: Joy Division manager; Factory co-founder

Lesley Gilbert: partner of Rob Gretton; witness

Richard Kirk: Cabaret Voltaire

Malcolm Whitehead: film-maker, Joy Division

Jon Wozencroft: witness

Lindsay Reade: wife of Tony Wilson; witness

Jill Furmanovsky: photographer

Dave Simpson: witness

Mary Harron: writer, Melody Maker

Annik Honor: witness

Gillian Gilbert: partner of Stephen Morris; witness

Anton Corbijn: photographer

Daniel Meadows: photographer

Dylan Jones: witness

Bernard Sumner: I felt that even though we were expecting this music to come out of thin air, we never, any of us, were interested in the money it might make us. We just wanted to make something that was beautiful to listen to and stirred our emotions. We werent interested in a career, or any of that. We never planned one single day.

Peter Hook: Ian was the instigator. We used to call him the Spotter. Ian would be sat there, and he d say, That sounds good, lets get some guitar to go with that. You couldnt tell what sounded good, but he could, because he was just listening. That made it much quicker, writing songs. Someone was always listening. I cant explain it, it was pure luck. Theres no rhyme or reason for it. We never honestly considered it, it just came out.

Stephen Morris: He was pretty private about what he wrote. I think he talked to Bernard a bit about some of the songs. He was totally different to how he appeared onstage. He was timid, until he d had two or three Breakers, malt liquor. Hed liven up a bit. The first time I saw Ian being Ian onstage, I couldnt believe it. The transformation to this frantic windmill.

Deborah Curtis: He was so ambitious. He wanted to write a novel, he wanted to write songs. It all seemed to come very easily to him. With Joy Division it all just came together for him.

Tony Wilson: I still dont know where Joy Division came from.

Factory landscape, Greater Manchester, October 1977 (Jon Savage)

Tony Wilson: I think that psychogeography and the concept of the city was at the centre of situationism in the fifties in France, and the degraded city was part of Joy Divisions life: Macclesfield boys, Salford boys, and there is the city Manchester. The idea of the city is a theme that runs through this whole thing, Manchester being the archetypal modern city.

C. P. Lee: They used to say that what Manchester thinks today, London does tomorrow, and in the nineteenth century this was an amazing place for innovation. Salford, which isnt part of Manchester but sits side by side, had the first street lighting, the first trams. All these things came out of Manchester: municipal housing, the first public lending library all of these great, fantastic innovations that we assume are twentieth century emerged in the nineteenth century.

But at the same time there is a tension inherent within all of this, and the tension evolves around the great unwashed, the working classes. Theyre there as a mob. Now some of the movers and shakers within Manchester want to work with them and want to make things better, want to move the city on, but there are other people who regard them as very, very dangerous, so you get these tensions.

So youve an area like Angel Meadows, so called because the dead were buried in such shallow ground that when it rained, it washed away the topsoil and the bones would stick out. Areas where policemen would only go round in twos. In the thirties my father was a policeman and went round there with another officer. It was three in the morning and people were sat outside, and my dad said, Why are they sat there? And he said they stay there and get as drunk as possible for as long as possible, so that when they go to bed they sleep, despite the bed bugs.

You have a city which exists in great innovation, with wealth which has been generated by Cottonopolis, generated by the future, visions of the future. Things like the Ship Canal, which is fantastic. The sea is thirty miles away at Liverpool, but Manchester doesnt sit there and take it. It says, Well bring tsea to the city, and they build the Ship Canal, and it comes here and its fantastic.

There are docks in Salford. It becomes known as the Barbary Coast and its full of dusky Lascars, its full of Italianates, its full of Mediterraneans and Spaniards who swan around with earrings and neck scarves, and its fantastic. There are men with monkeys on their shoulders. The docks bring in everything to Manchester, and it becomes a fantastically opulent melting pot of different influences and different styles, but at the same time, underneath it is an underbelly of the working classes, who havent exactly got a slice of the cake.

In the early years of the nineteenth century you have a massive political movement which starts developing in the north-west of England, and its the Chartists and its the free-traders, and what they basically want is what we have now, which is universal suffrage. They have a massive demonstration in 1819 at St Peters Field in Manchester, and what do you do when people want the vote? You send in the cavalry, and the cavalry and the yeomanry went in and massacred the crowds that were there. Hundreds were injured, fifteen dead, probably more.

This was celebrated by the erection through public subscription of the Manchester Free Trade Hall, which becomes a gigantic epicentre of psychogeographical energy. Every major artist and musician of the twentieth century appeared in the Free Trade Hall. It was the site of political debate. When trade unions went on strike they had their meetings there, Louis Armstrong played there, Bob Dylan was booed and heckled in the Free Trade Hall in 1966, the Sex Pistols played there in 1976, and in 1996 the Dalai Lama did his last blessing to the people of Manchester in there.