A big thank you to all the people I interviewed: Iris Bates, Ernest Beard, Derek Brandwood, Kelvin Briggs, Oliver Cleaver, Steve Doggart, Franck Essner, Peter Hook, Michael Kelly, Terry Mason, Paul Morley, Stephen Morris, Tony Nuttall, Patrick OConnor, Lindsay Reade, Peter Reid, Richard Searling, Bernard Sumner, Sue Sumner, John Talbot, Anthony Wilson and Helen Atkinson Wood.

Special thanks to Peter Bossley for his guidance and encouragement, without which I would still be grinding my teeth in my sleep!

Kisses to Wesley.

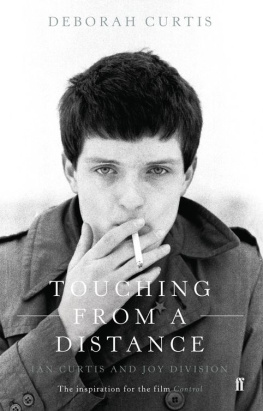

Ian Curtis was a singer and lyric writer of rare, mediumistic power: his songs and performances for Joy Division conveyed desperate, raging emotions behind a dour, Mancunian faade. There were four in Joy Division Curtis, Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook and Stephen Morris but Ian was their eyes and ears: it was he who propelled them into uncharted territory songs like Dead Souls which, cold as the grave, has the infinity of a Gustave Dor hell.

Its easy to forget, now that Manchester is an international music city, just how isolated Joy Division were. At a time when the main venue of communication was the weekly music press, Joy Division shunned interviews: they survived and prospered through concerts, badges, seven-inch singles and word of mouth. During their last six months, the modern youth media began: style magazines like TheFace and i-D, access programmes like SomethingElse, which Joy Division hi-jacked with a manic performance of Shes Lost Control.

Joy Division were not punk but they were directly inspired by its energy. Like punk, they used pop music as the means to dive into the collective unconscious, only this was not Dickensian London, but De Quinceys Manchester: an environment systematically degraded by industrial revolution, confined by lowering moors, with oblivion as the only escape. Manchester is a closed city, Cancerian like Ian Curtis: he remains the citys greatest song poet, capturing its space and its claustrophobia in a contemporary Gothick.

Manchester is also a big soul town: you breathe in black American dance music with the damp and pollution. Asked to write a song based on N. F. Porters Northern Soul classic, Keep On Keeping On, Joy Division took the orginals compulsive riff and blasted off into another dimension: Trying to find a way, trying to find a way to get out! Despite the dark lyric, traces of the originals hard-bitten joy and optimism come through, like a guide track erased in the finished master.

I was living in Manchester then, a Londoner transplanted to the North West; Joy Division helped me orient myself in the city. I saw this new environment through their eyes Down the dark street, the houses look the same and felt it through the powerful atmosphere they generated on records and in concert. Their first album, UnknownPleasures, released in June 1979, defined not only a city but a moment of social change: according to writer Chris Bohn, they recorded the corrosive effect on the individual of a time squeezed between the collapse into impotence of traditional Labour humanism and the impending cynical victory of Conservatism.

Live, Joy Division rocked, very hard, but that was not all. Ian Curtis could give performances so intense that youd have to leave the hall. Most performers hold something back when theyre in front of an audience: what is called stagecraft or mannerism is, in fact, necessary psychic self-protection. Flanked by his anxious, protective cohorts Bernard Sumner and Peter Hook Ian Curtis got up, looked around and surrendered himself to his visions. This was not done in the controlled environment of a concert hall or studio, but in tiny, ill-equipped clubs which could at any moment explode into violence.

When youre young, death often isnt part of your world. When Ian Curtis committed suicide in May 1980, it was the first time that many of us had had to encounter death: the result was a shock so profound that it has become an unresolved trauma, a rupture in Manchesters social history which has persisted through the citys worldwide promotion as Madchester, and through the continuing success of New Order, the group formed by Joy Divisions remaining trio. As Curtis himself sang on Komakino: Shadow at the side of the road/Always reminds me of you.

Deborah Curtis was the last person to see her husband alive: at the most basic level, her memoir is the exorcism of the loss, guilt and confusion that followed his act of violence in their Macclesfieldhome. It tells us also about what has been much rumoured but never known: the emotional life of this most private of men. Much of the information in this book is printed here for the first time an act of revelation that shows how deep the need is to break the bonds of Mancunian taciturnity.

It also tells us something that is ever present but rarely discussed: the role of women in the male, often macho, world of rock. Deborah Curtis is the wife who supported her husband, but who got left behind. Theres a chilling scene where, heavily pregnant, Deborah goes to a Joy Division concert, only to be frozen out by an associate because she is not glamorous enough, because, in her own words, how, can we have a rock star with a six-months-pregnant wife standing by the stage? And so, the cruelties begin.

There is another question which this book raises, as chilling as it is unanswerable. Deborah Curtis writes about the reality behind the persona, the fact that Ian Curtis had a condition epilepsy which was worsened by the exigencies of performance. Indeed, his mesmeric stage style the flailing arms, glossy stare and frantic, spasmodic dancing mirrored the epileptic fits that he had at home, that struck a chill into his intimates. Did people admire Ian Curtis for the very things that were destroying him?

I applaud Deborah Curtiss courage in writing this book, and believe that it will help to heal this fifteen-year-old wound. It may also help us to understand the nature of the obsession that continues to stalk rock culture: the romantic notion of the tortured artist, too fast to live, too young to die. This is the myth that begins with Thomas Chatterton and still carries on, through Rudolf Valentino, James Dean, Sid Vicious, Ian Curtis and Kurt Cobain. TouchingfromaDistance shows the human cost of that myth.

Jon Savage

1995

Once upon a time there were three bands. It was 26 May 1977 and Id gone to see Television and Blondie at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. In the bar during the changeover I bought a copy of Shytalk Not suitable for adults, a fanzine from Manchester it said on the front. Somewhere in the six or seven stapled-together A4 pages was a piece about new bands of the new wave who were having a bit of drummer difficulty. I have an eye for that sort of thing. One was a band called Warsaw, one called The Fall and the other V2. I could do that, I thought. Ill ring up tomorrow. But dithering, I did nothing instead.

A month or so later, in Macclesfield, I was avoiding going back to work. I found myself looking in Joness music-shop window with its shiny unaffordable guitars and musical whatnots. Stuck there in the corner was a handwritten postcard which seemed to shout, Drummer wanted for local New Wave Band, Warsaw. Phone Ian @@@@@@@@. There was that Warsaw again. This time the Macclesfield phone number made my mind up for me.