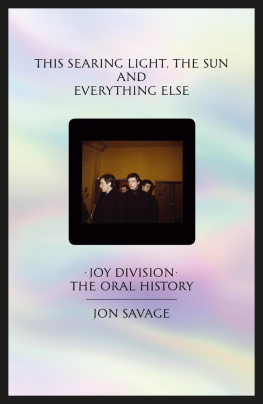

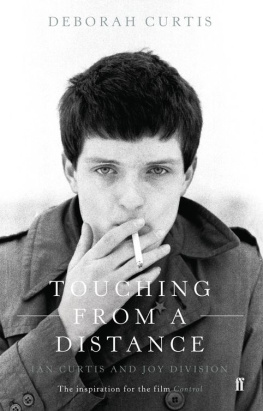

also by Deborah Curtis touching from a distance:

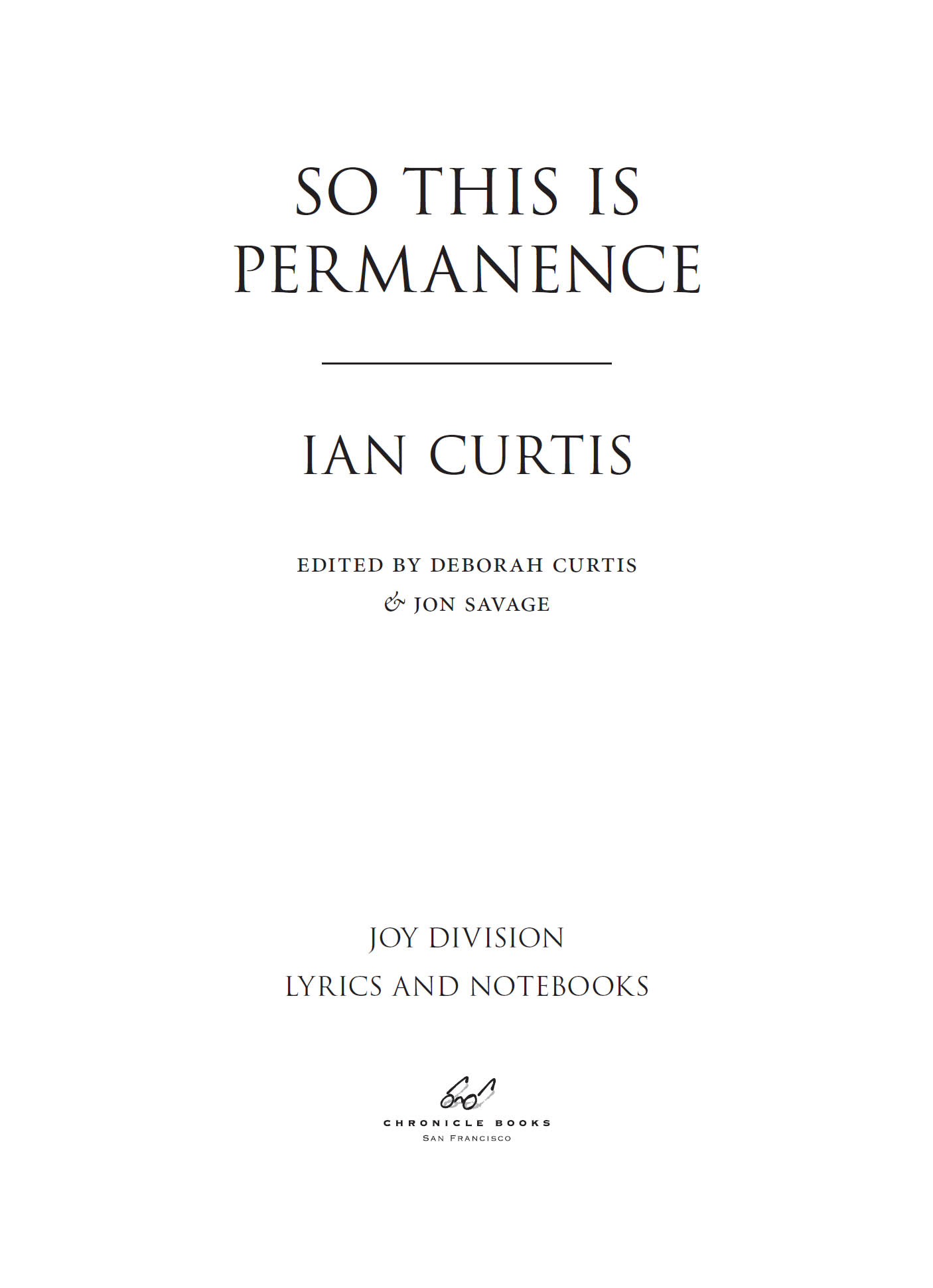

Ian Curtis and Joy Division also by Jon Savage englands dreaming:

The Sex Pistols and Punk Rock the faber book of pop:

edited with Hanif Kureishi teenage:

The Creation of Youth 18751945  First published in the United States of America in 2014

First published in the United States of America in 2014

by Chronicle Books LLC.

First published in Great Britain 2014

by Faber & Faber Ltd

Bloomsbury House, 7477 Great Russell Street,

London wc1b 3da Typeset by Faber & Faber Ltd All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form

without written permission from the publisher. Lyrics Fractured Music / Universal Music Publishing

Foreword Deborah Curtis, 2014

Introduction Jon Savage, 2014 The right of Ian Curtis to be identified as author of this work

has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988 The right of Deborah Curtis and Jon Savage to be identified as editors

of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 constitute a continuation of the copyright page.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available. isbn 9781452138459 ( hc )

isbn 978-1-4521-4650-8 ( epub, mobi ) Chronicle Books LLC 680 Second Street San Francisco, California 94107 www.chroniclebooks.com

FOREWORD BY DEBORAH CURTIS

I was introduced to Ian in Macclesfield in 1972 by a boy he called his brother. This singular teenager, who didnt go to the youth club with the other kids, stood posing on the balcony of his parents flat. He was wearing eye makeup, tight jeans and a fun fur jacket; some would have laughed but there was a reverence about that first encounter.

He appeared to be waiting for the introduction. It felt preordained. He was studious: winning a school History prize in 1971 and the Divinity prize in 1971 and 1972, enjoying Ted Hughes and Thom Gunn and later Chaucer. He had a black ring binder with subject dividers which he had marked Lyrics and Novel, and I felt privileged that he had trusted me enough to let me see the extent of his ambitions. I was hooked; the romance of him being both a poet and a writer was too much to resist; and it was easy to settle into the lifestyle of being around him. He took me to gigs, introduced me to the diverse people in his life and when I realised that our future was to be together nothing else seemed to matter.

Apart from his vinyl collection and reams of music papers his bedroom was impersonal, especially considering his complex theatrical personality. There were no piles of clothes or makeup or clutter of any kind. He was tidy and cared obsessively how things looked and sounded, always striving for perfection. He juggled his relationships easily, moving between different peer groups, collecting other people and their experiences. He approached difficult subjects so obliquely that I couldnt detect whether they were pertinent to him personally. I didnt understand why he wanted to talk about a local boy who was said to be suffering from manic depression; it seemed like gossip and was uncharacteristic of him.

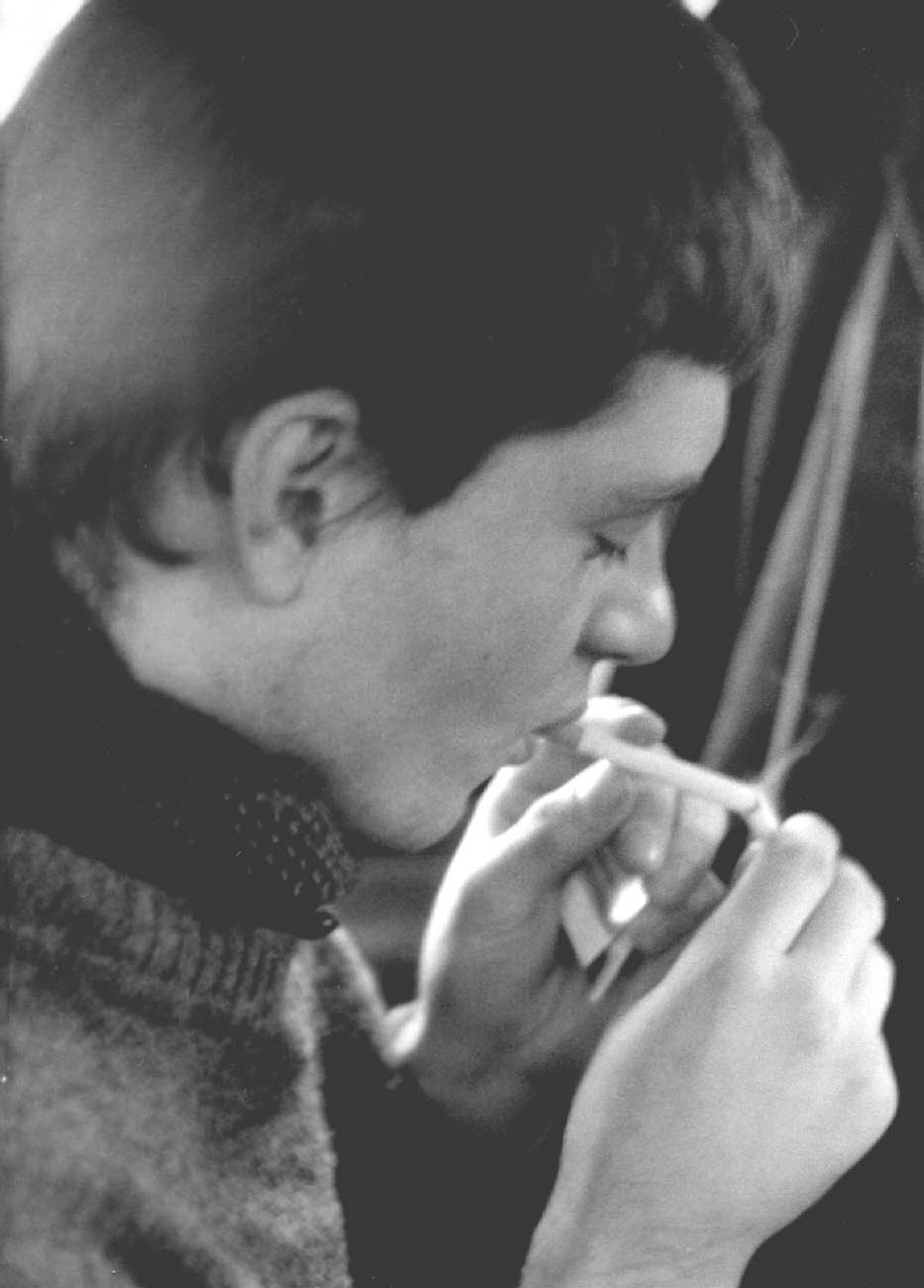

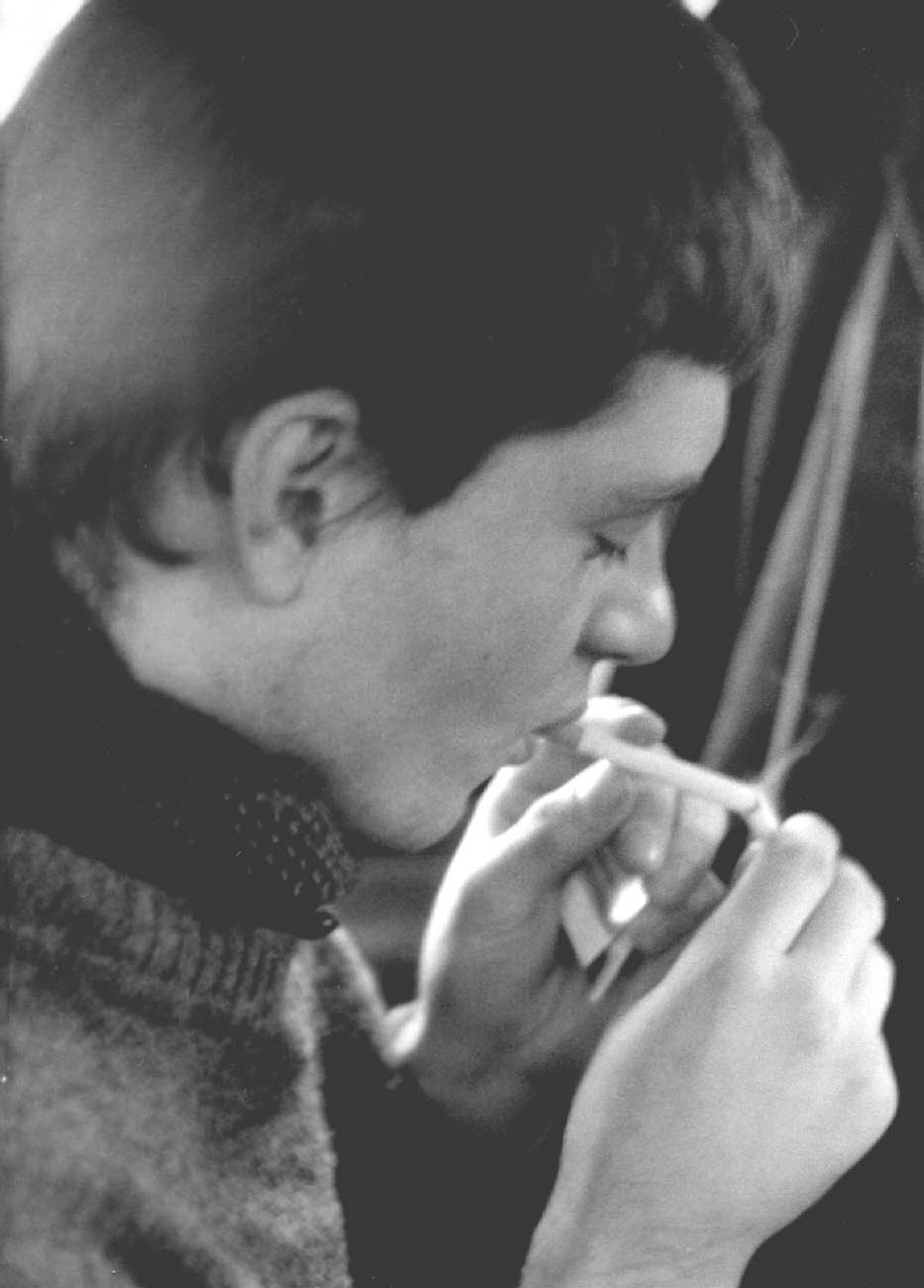

He explained any of his own unusual behaviour, absences or seizures as flashbacks and it was made clear that they were not up for discussion. There were rumours that Ian had been in trouble at school but his friends laughed, the Curtis family moved to Manchester and it was all brushed away. Their front lounge became his bedroom; again it was tidy and functional, all he seemed to need in life were his records, the music press and cigarettes. When I stayed at the weekend he would put on a record and we would sit on the floor. Each album had to be listened to from beginning to end uninterrupted and he loved explaining the story behind the lyrics to me. He liked to read Oscar Wilde or Edgar Allan Poe and he would make sure we were home on Saturday nights in time to watch the horror films.

We married and for a while we lived with his grandparents. Ian began buying reggae music; he would wait until we were alone before he carried his record player into the lounge, the thick net curtains and the heavy drapes blocking the daylight. Ian no longer had a room of his own but he didnt put a hold on his plans. Ian liked to call into the record shop in Moss Side shopping centre to listen to the latest releases and from there he found out where the best reggae clubs were. We went to The Mayflower and The Afrique and got out of the house as much as possible. He saw it as an opportunity to meet the people who lived in that area, to immerse himself in another culture.

We soaked up the atmosphere in the local shops and went out in the evenings to collect the money for the football coupons. No matter how late we were out the night before, Ian would insist that we were up and in work by 8 a.m. so we could finish early and go out again. Our first home was in Chadderton where it was quiet, inconvenient for nights out in Manchester and far away from our friends in Macclesfield. Our lounge was the only room that was heated and comfortable, but somehow, even without the necessary privacy, Ian began to write again, keeping his work in a plastic carrier bag. It was from that address that we set off for the Mont-de-Marsan Punk Rock Festival; after that trip our world opened up and everything felt possible.

We put the house on the market knowing only that we werent happy there. After a short stint back at his grandparents we moved to Macclesfield. The house on Barton Street was double-fronted, with a kitchen and lounge on one side of the staircase and another completely separate room on the other. I saw a beautiful, cosy cottage within walking distance of the town centre but Ian saw a room all of his own: a space to write, small enough for the electric fire to heat and long enough for him to pace up and down with his thoughts. We couldnt wait to move in and the first task was to make Ians room ready: he painted it sky blue, and we acquired a radiogram. Ians plastic carrier bag had its place on the blue carpet next to the long blue Habitat sofa, and his albums leaned stacked against the wall behind the door.

It didnt cross my mind that one of the shared rooms should be first on the agenda for refurbishment: Ians writing career was paramount for both of us. He would move the ashtray from the floor to the top of the wooden fire surround depending on whether he was pacing or sitting. He was a neat smoker, never allowing ash to accumulate; often the only sound would be the click of his long thumbnail on the filter tip of his Marlboro before he balanced it on the edge of his ashtray to pick up his pen. He would write a line, put the pen down and then knock more ash from his cigarette. He took the carrier bag with him to rehearsals, on tour, and to meetings. When he came home he would stand on the doorstep, pushing the door open as he turned the key; the bag rustling noisily as he fumbled was always the first sound I heard; then straight to the blue room to stow his writing away before he took off his coat and hung it in the cupboard.

There was never anything superfluous in his life as he chose his surroundings as carefully as he chose his words. Ians art was crucial to him and he did not consider songwriting a mere commercial endeavour. So it was unsurprising that he turned to darker, more serious subjects to inspire him. Not specifically the Holocaust but war itself: any war would have been the perfect vehicle for Ians interpretation of the world. In conversation he would touch vaguely on his Irish family history and on his fathers subsequent service in World War II. Its debatable whether he drew on those stories to fuel his creative process or whether he turned to writing because speaking out was frowned upon.

Next page

First published in the United States of America in 2014

First published in the United States of America in 2014