Contents

For my mother, Rachel

The grand object of traveling is to see the shores of the Mediterranean. All our religion, almost all our law, almost all ourarts, almost all that sets us above savages, has come to us from the shores of the Mediterranean.

Samuel Johnson

Everyone gets everything he wants. I wanted a mission. And for my sins they gave me one.

Captain Willard, Apocalypse Now

Introduction

A Long Story

Of that versatile man, O Muse, tell me the story, how he wandered both long and far after sacking the city of holy Troy. Many were the towns he saw and many the men whose minds he knew, and many were the woes his stout heart suffered at sea as he fought to return alive with living comrades. Them he could not save, though much he longed to, for through their own thoughtless greed they diedblind fools who slaughtered the Suns own cattle, Hyperions herd, for food, and so by him were kept from returning. Of all these things, O goddess, daughter of Zeus, beginning wherever you wish, tell even us.

The Odyssey, Book I

THINGS GO WRONG, plans fail, fate makes sport of our best intentions. We say one thing and do another; nothing turns out as we expect. Its an unpredictable life, and we comfort ourselves by blaming greater powers: If you want to make God laugh, we say, tell him your plans, and most modern Westerners can be grateful to at least have only the one God whose laughter concerns us. Think, though, of the ancient Greeks. The Greeks had an entire pantheon of gods; the Greeks had gods like we have siblings, cousins, in-lawsand just as busy, just as nosy, too. So the ancient Greeks knew their plans could elicit laughterand expect troublefrom not just one source but a dozen. That was the gods favorite thing, interfering with peoples plans. Or more accurately, helping people interfere with their own.

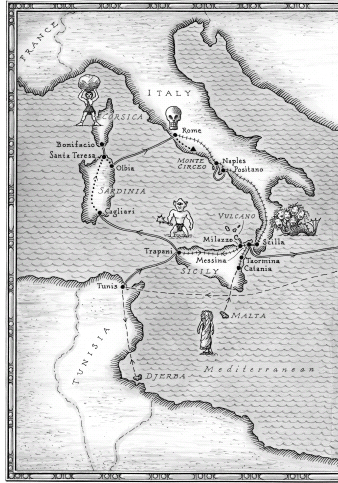

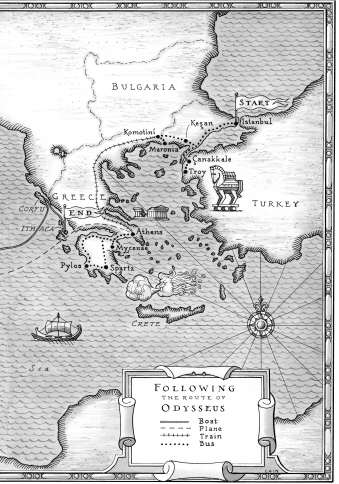

It still is, I think. So not long ago, when I briefly took to making plans, I should have been listening for that laughter. You could say I went looking for it. It began, after all, with a public promisewhich the gods made sure I broke, almost instantly. Afterward came a headlong journey, filled with discovery, wonder, and adventure, which seems like their kind of joke, tooat least, theyve been using it for a while. In the end, of course, its a long story. You can start almost anywhere.

So start with James Joyce.

ON JUNE 15, 2001, I swore, out loud and on the radio, that I would never, ever read Ulysses.

Joyces Ulysses is regularly crowned the most important novel of the twentieth century. Nearly eight hundred pages long, filled with thousand-word stream-of-consciousness run-on sentences, classical references, and asides in various languages, Ulysses (the Romanized name, of course, of the Greek hero Odysseus) is considered the birth of modern literature. A modern retelling of the ten years of adventure described in The Odyssey of Homer, Ulysses takes place all on one dayJune 16, 1904, in Dublin. Advertising salesman Leopold Bloom stands in for Odysseus, and the books episodes have their origins in Homer: Theres a Cyclops episode and a Sirens episode and much more, all complex and modern and hard to follow. Friends and experts had been pressing Ulysses on me for decades, but despite countless frustrating attempts I had never been able to get very far in it.

Then came the early summer of 2001, which seemed to bring an Odyssey onslaught. The movie O Brother, Where Art Thou? the Coen Brothers free retelling of the Odyssey story, came out on DVD. Cold Mountain, the Charles Frazier novel of a reluctant soldier making his adventurous way home from a horrific war, sat on every night table and was in development as a film. When my oldest friend asked me to read something at his wedding, I was almost unsurprised when another friend recommended Ithaca, a lovely reconsideration of the wanderings of Odysseus by poet Constantine Cavafy.

And, most especially, Bloomsday approached. Among its devotees Ulysses has become less a book than something of a cult, and the feast day for that cult is June 16, Bloomsday. All over the world on that day people read Ulysses aloud, celebrate it in drama and song, and, above all, get drunk. In Dublin, Mecca for Ulysses cultists, thousands of people gather to enact scenes from the book, engage in panel discussions about the books opacities, and actually retrace the steps of the books characters. This outpouring of obsession toward a book I found unreadable drove me mad. After all, Im a writerIm a literary guy. And I believe this obsession makes literary guys look like pseudointel-lectual nitwits. I wanted to distance myself from those nitwits. So in June 2001 I read a brief essay on the radio announcing that after decades of attempts I was officially declaring Joyces book not worth the trouble: I was using that years Bloomsday celebration to forever renounce Ulysses. The book ends with Molly Blooms forever-quoted benedictory, yes I said yes I will Yes. So on the day its adherents worshipfully followed the footsteps of its fictional characters, I pledged to finally consign the book to my shelf unread, echoing its conclusion: no I said no I wont No.

I CANT SWEAR it was the work of the gods, but I was a liar inside a month.

Someone who heard my essay convinced Matthew, a bookstore manager well read in Joyciana, to lead a Ulysses reading group. And because I had written the scornful essay that got the group started, they invited me to join. I had just publicly sworn never to read Ulysses as long as I lived; doing exactly the opposite made for a pleasing irony. I joined up. Matthew led us through complex schema and thickets of commentary, and over four months alternated between coaxing and dragging us through Ulysses. Occasionally, with Matthews help, I was thrilled by a pun in two languages, a sly classical reference; more often I complained. Challenged and interested, I still rarely doubted the good sense of my original inclination to give the book up.

And for me, most important was that the farther we moved along, the less Joyce commanded my attention. Instead, I thought more and more about the Homeric tales behind it all. I grew interested in The Odyssey itself.

I couldnt help thinking: What gives? Everywhere you turn, The Odysseyand its not like its something new. For three thousand years, weve been telling each other the same story. Whether its Joyces book or Tennysons poems, a symphony by Max Bruch or heavy metal by Symphony X, pictures by Matisse or Chagall, were still finding new ways to tell each other the episodes from that old story. I wondered why.

Next page