Human Origins

7 million years and counting

NEW SCIENTIST

Contents

Series introduction

New Scientists Instant Expert books shine light on the subjects that we all wish we knew more about: topics that challenge, engage enquiring minds and open up a deeper understanding of the world around us. Instant Expert books are definitive and accessible entry points for curious readers who want to know how things work and why. Look out for the other titles in the series:

The End of Money

How Your Brain Works

The Quantum World

Where the Universe Came From

How Evolution Explains Everything about Life

Why the Universe Exists

Your Conscious Mind

Machines that Think

Scheduled for publication in 2018:

How Numbers Work

A Journey Through The Universe

This is Planet Earth

Contributors

Series Editor: Alison George, New Scientist

Editor: Michael Marshall, freelance science journalist based in Devon, UK

Instant Expert Series Editor Jeremy Webb, New Scientist

Guest contributors

Justin L. Barrett is a professor of psychology and chief project developer for Fuller Theological Seminarys Office for Science, Theology, and Religion Initiatives. He is the author of Born Believers: The Science of Childrens Religious Belief (2012). He writes about our natural receptivity to religious ideas in .

Michael Bawaya is a the editor of American Archaeology magazine. He lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico and writes in about human migration into the Americas.

David Begun is a professor of anthropology at the University of Toronto, Canada. He is author of The Real Planet of the Apes (2015) and writes here about the dawn of the apes in Europe in .

Ara Norenzayan is a professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. He is the author of Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict (2013). In he discusses religions critical role in helping societies grow.

Mark Pagel is a professor of evolutionary biology at Reading University, UK, a fellow of the Royal Society, and author of Wired for Culture: Origins of the Human Social Mind (2012). In he describes why teaching is critical to our cultural evolution, and asks why language evolved.

Pat Shipman is a palaeoanthropologist and retired Adjunct Professor of Biological Anthropology at Pennsylvania State University. Her latest book is The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction (2015). Her work on the relationship between humans and wolves appears in .

Thanks also to the following writers and editors:

Robert Adler, Claire Ainsworth, Shanta Barley, Colin Barras, Emily Benson, Alyssa A. Botelho, Catherine Brahic, Ewen Callaway, Andy Coghlan, Kate Douglas, Alison George, Jessica Hamzelou, Jeff Hecht, Bob Holmes, David Holzman, Jude Isabella, Ferris Jabr, Dan Jones, Alice Klein, Will Knight, Roger Lewin, Mairi Macleod, Phil McKenna, Rachel Nowak, Jan Piotrowski, James Randerson, Kate Ravilious, David Robson, Michael Slezak, Laura Spinney, Mio Tatalovi, Jeremy Webb, Clare Wilson, Sam Wong, Aylin Woodward, Ed Yong, Emma Young.

Introduction

There can be no more profound question than Where do we come from? Since our ancestors figured out how to think, we humans have wondered about our origins, but it is only within the last few centuries that we have tackled the question scientifically.

The story of the study of human evolution is an epic one, full of extraordinary discoveries, daring adventures and (often) spectacularly vehement arguments. It encompasses a swathe of technical disciplines, and forces us to ask deep questions about who we are as a species. This book is your introduction to the subject.

The first seven chapters tell the story of human evolution in chronological order, beginning with the earliest primates, moving through the earliest ape-like hominins, and concluding with the rise of modern civilization. The final three chapters then step back to ask the three biggest questions: what is so special about us, how did we get that way, and what do we still not know?

That last point is a crucial one. We should admit in advance, with apologies, that no reader will get to the end of this book and find that they understand how humanity evolved. Our understanding of human evolution has been upended, or at least seriously complicated, by a swathe of remarkable discoveries made since the year 2000. So you wont find the ultimate truth here, but you will find plenty of facts, our best explanations for them and, we hope, the right questions to ask.

Michael Marshall, Editor

Distant origins

The story of our origins begins tens of millions of years ago. In the wake of a mass extinction that wiped out all the dinosaurs except for birds and a host of other creatures, a new group of animals arose. They were small and probably seemed utterly insignificant at first. But they would spread to every continent and ultimately change the face of the planet. They were the primates.

The story of primate evolution spans 55 million years and hundreds of species. But from the point of view of our own evolution, there are four key steps:

1 The original primates

2 The higher primates or simians the group that includes monkeys

3 The apes, especially chimpanzees

4 The rise of hominins like us.

In this chapter we will focus on the first three steps. The following six chapters will cover the hominins.

Meet Archie

Our distant ancestors most likely evolved in Asia, in a hothouse world newly free of dinosaurs. More than 55 million years ago, in the lush rainforests of what is now east Asia, a new voice was heard in the animal chorus: the cry of the first primate.

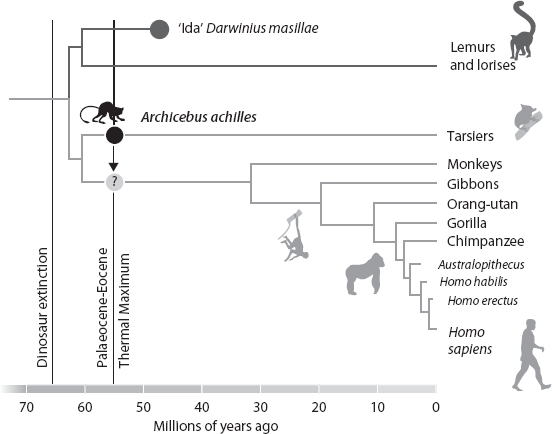

A fossil unveiled in 2013 might give us an idea of what this crucial ancestor looked like. Archicebus achilles is the earliest primate skeleton ever found (see ). It also strongly suggests that our lineage evolved in Asia, several million years earlier than we thought, and links the evolution of primates to the most extreme episode of climate change of the last 65 million years.

FIGURE 1.1 The evolution of the primates, apes and hominins: Archicebus achilles is the oldest primate found so far. Analysis of the fossil places it in the tarsier lineage but it may yet turn out to be a human ancestor.

The American palaeontologist Christopher Beard and his colleagues found Archicebus in eastern China, just south of the Yangtze River. It dates from 55 million years ago, has the relatively small eyes of an animal active during the day and the sharp molar teeth of an insect-eater. Significantly, it also has the hind limbs and flexible foot of a primate that had already taken to leaping between branches and gripping them with its feet characteristics that we lost only when our ancestors left the trees just a few million years ago. In fact, a 2013 study revealed that at least 1 in 13 of us still has a flexible foot a trait, it seems, that may be traceable all the way back to an animal very like Archicebus.

The first analysis of Archicebus placed it, not on our direct line, but with our next-door neighbours, the tarsiers of south-east Asia. However, it is hard to say for sure which group it belongs to.