About the Authors

Glenn Adamson is the Nanette L. Laitman Director of the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City. He was, until Autumn 2013, Head of Research at the V&A, where he was active as a curator, historian, and theorist. His publications include Thinking Through Craft (2007), The Craft Reader (2010), Invention of Craft (2013), and Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970 to 1990 (2011). He is also the co-founder and editor of the triannual Journal of Modern Craft. Adamson holds a PhD from Yale University (2001), and he has taught and lectured widely at universities and art schools including the Royal College of Art, University of Wisconsin, RISD, California College of the Arts, and Cranbrook Academy of Art.

Julia Bryan-Wilson is Associate Professor of contemporary art at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the author of Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era (2009), and the editor of October files: Robert Morris (2013). A scholar and critic, Bryan-Wilson has written about Laylah Ali, Ida Applebroog, Simone Forti, Ana Mendieta, Yvonne Rainer, Yoko Ono, Harmony Hammond, and Sharon Hayes among other artists, for publications including Art Bulletin, Artforum, Grey Room, The Textiles Reader, October, and the Journal of Modern Craft, as well as many exhibition catalogs.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Make Your Mark: The New Urban Artists

Nature Morte: Contemporary artists reinvigorate the Still-Life tradition

Raw + Material = Art: Found, Scavenged and Upcycled

Big Art / Small Art

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

When future art historians look back at the present day, it is possible that it will be the sheer proliferation of our art that will strike them most, rather than its content. No era has created so much art, or art of such eclecticism. The profusion of artistic production in all its variety is bewildering, so much so that apart from its apparently unstoppable expansion, it seems impossible to summarize arts tendencies in the past half-century or so. There appear to be no obvious barriers of acceptability left to break through. Ideas such as avant-garde provocation, or newness, or originality have for contemporary artists become timeworn clichs.

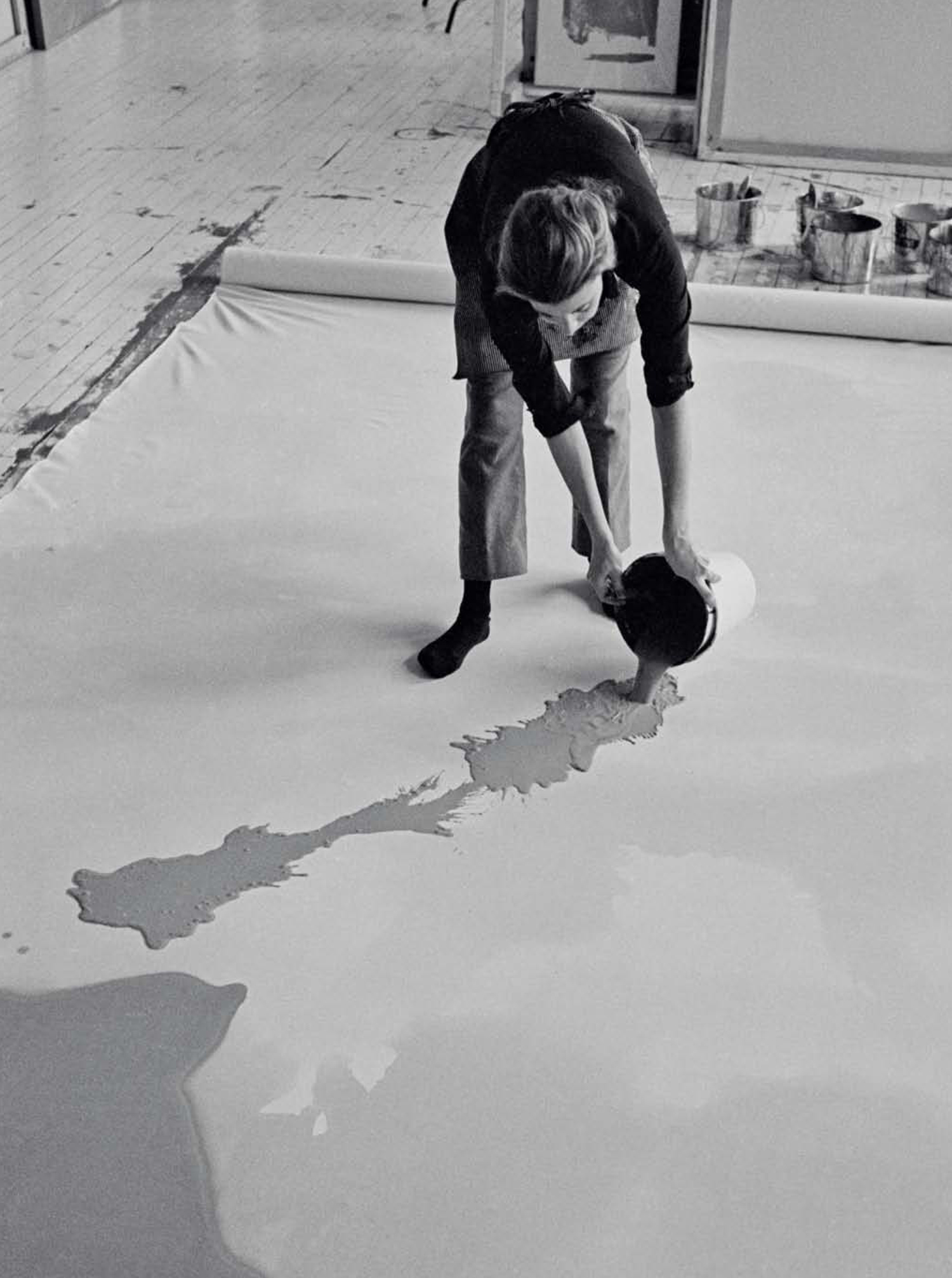

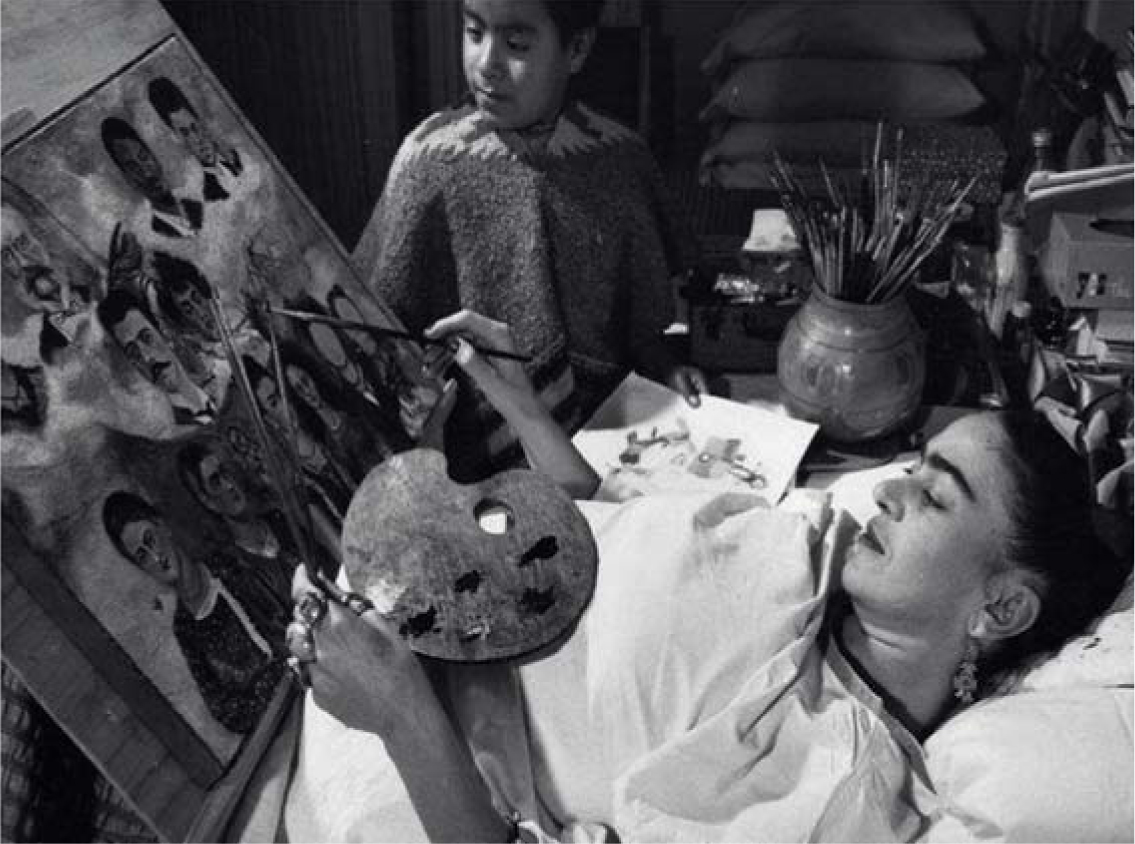

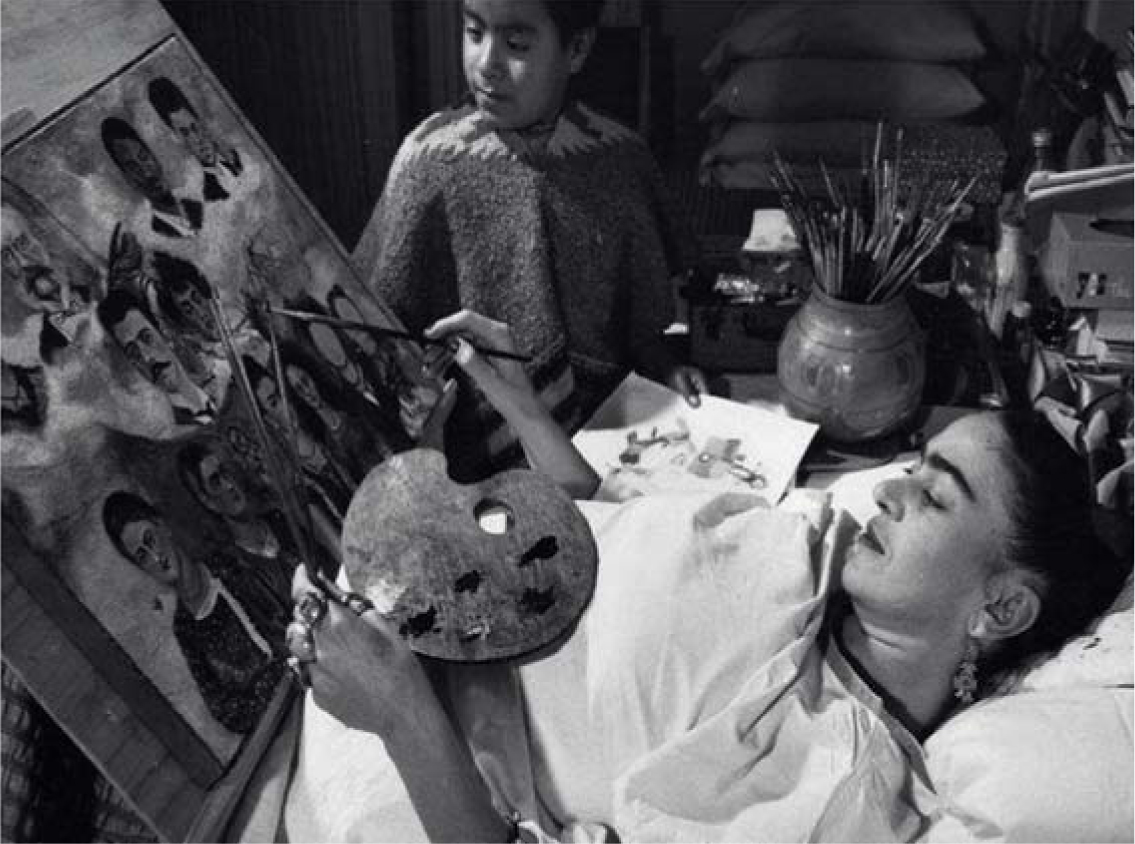

Frida Kahlo painting in bed, 1950. Photograph by Juan Guzman

Yet there is one arena in which art today is changing dramatically, and departing radically from precedent: the ways that it is made. Long gone are the days when art was typified by the atelier model of production, in which one artist makes unique objects in a studio or, in the case of Frida Kahlo, after an accident, from the confines of a bed. This image of an artist so committed to her practice that she paints even while convalescing from an incident of serious bodily injury marks one particular vision of an artist at work. Kahlo learned to paint while lying down, and this photograph presents not the typical upright, able-bodied maker in a workroom, but rather an alternative space of vibrant artistic activity. It is the full spectrum of sites of production, from artist loft to factory floor to database, that this book considers.

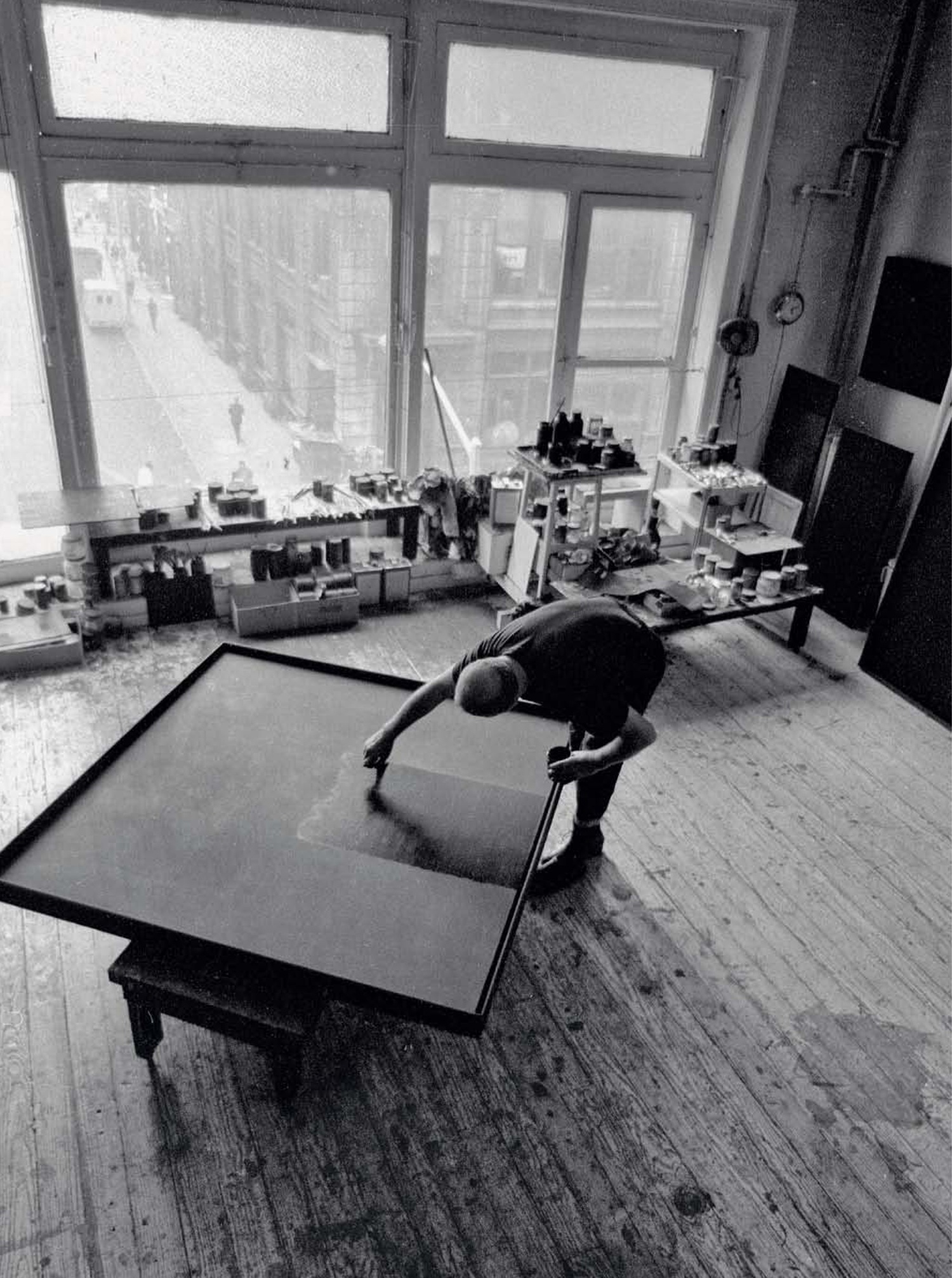

Bed-In for Peace, 1969. John Lennon and Yoko Ono receiving journalists in their bedroom at the Hilton hotel in Amsterdam, during their honeymoon, March 25, 1969

To illuminate how artistic processes have expanded and diversified since this photograph was taken of Kahlo, let us take a quick tour through a small sample of other instances of artists beds, beds that, like Kahlos, function as more than just places of heterosexual conception, rest, and imaginative escape. We take this tour of beds (it could also be thought of as a detour) in part because we want to make concrete from the very beginning our overarching point about how multiple artistic making has become. We are also modeling in these opening pages our practice for the entire book, which is to construct an argument insistently driven by and through a series of tangible examples.

Consider Robert Rauschenbergs Bed (1955), a combine or assemblage in which the artist incorporated a pillow and quilt, painting atop them with reckless abandon. In this work, Rauschenberg uses found objects: what Marcel Duchamp called readymades. This strategy, in which a pre-existing thing is appropriated into the situation of art, initially appears to deskill the act of making. Because Duchamp could simply purchase his readymades a urinal, a bottle rack, or a shovel he did not need any of the traditional skills of a sculptor.

This strategy has rightly been perceived as a major conceptual disruption in the pattern of art-making, and one that still resonates today. Thus his use of the quilt as a kind of canvas also raises issues about the incorporation of low materials within high art.

In the following decade, Yoko Ono and John Lennon camped out on their honeymoon in hotel suites (in Amsterdam and Montreal) with banners affixed around them in protest of the US war in Vietnam, in Bed-In for Peace (1969). Rauschenberg had exploited the intimacy of the bed, normally considered a private realm, but Ono and Lennons performance was a choreographed, political effort that sought to capitalize on their already very public lives as global superstars, turning mass media attention into a vehicle for awareness about the anti-war movement. The making here extends out from the couples bed to the journalists photographs as they made their way into newspapers and onto TV. Those documents and their circulation are as much a part of the production as the artists working, that is, sitting in their nuptial bed talking to visitors about peace.

Next, think of Tracey Emins My Bed (1998), an installation of the artists bed and its immediate surroundings in all their messy disarray, including stained underwear, bedroom slippers, empty vodka bottles, and condoms. Emin did not produce or manufacture any of the everyday objects on display, but acquired and arranged them, apparently to replicate how her bed looked after she lay in it for days due to depression. What was encoded in the case of Rauschenbergs Bed was in this case explicit: this is making as a form of selection and re-enactment, charged with the artists affective state. For some viewers, it invited a mode of encounter more interactive than mere visual contemplation: two artists, Cai Yuan and Jian Jun Xi (who work together under the moniker Mad for Real), leapt onto Emins work at Tate Britain, stripped to the waist, and had a pillow fight. They called the piece

Next page