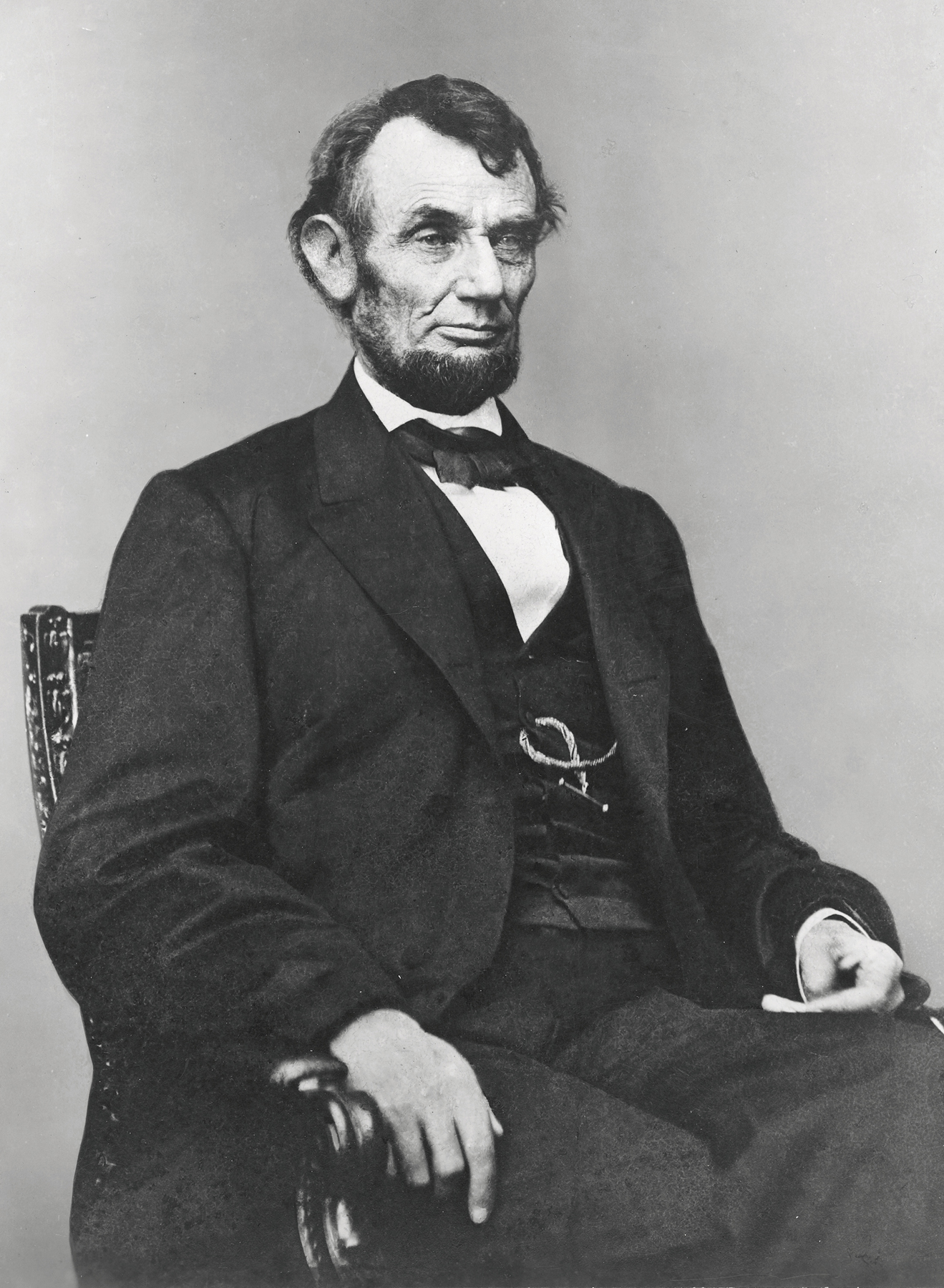

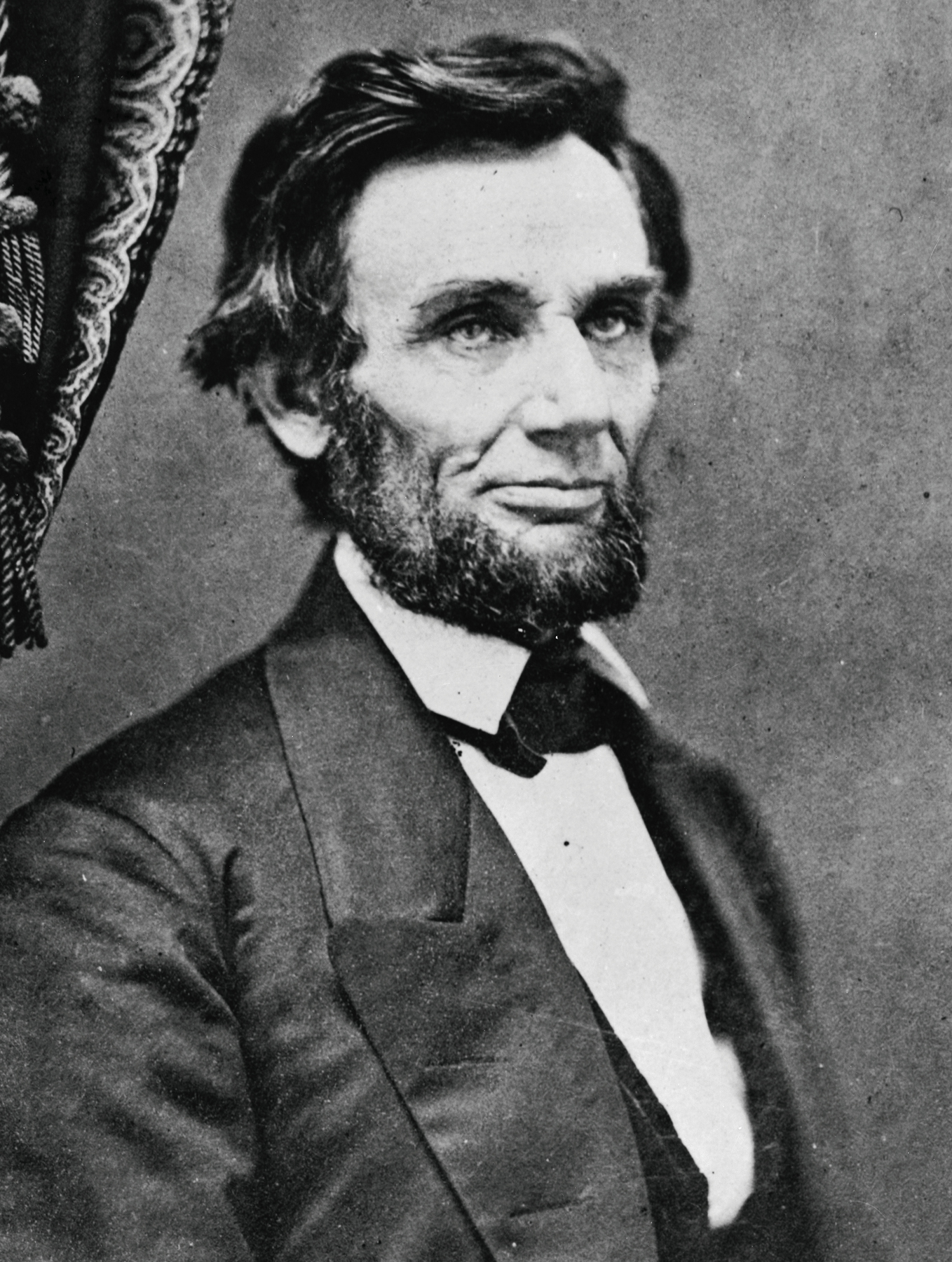

This portrait of Lincoln from February 1861 by Springfield photographer Christopher German is the last one made before Lincoln left Illinois for Washington to assume the presidency.

Writing of the thunderbolt 1862 announcement of Abraham Lincolns greatest act, the Emancipation Proclamation, in his History of the English-Speaking Peoples, Winston Churchill made a keen observation:

In Britain it was not understood why [Lincoln] had not declared Abolition outright. A political maneuver on his part was suspected. In America the Democratic Party in the North was wholly opposed. In the Federal armies it was unpopular. At the Congressional elections in the autumn of 1862 the Republicans lost ground. Many Northerners thought that the President had gone too far, others that he had not gone far enough. Great, judicious, and well-considered steps are thus sometimes at first received with public incomprehension.

Churchills points were well taken. At the time it was issued, Lincolns proclamation left both ardent antislavery and rigidly proslavery advocates dissatisfiedabolitionists because it failed to free slaves everywhere, slaveowners because it freed them anywhere. For good measure, its announcement also agitated Union loyalists in slave-holding border states, exempted from the order but sensitive now to the inevitability of freedom. The edict managed as well to outrage countless Federal soldiers who believed they had enlisted in the army solely to preserve the government, not to free slaves. And the proclamation vexed anti-Abolitionist, pro-Democratic Party Union generals, along with whites in the Confederacy, and for good measure the British press, which feared it would ignite a servile war that would cause blood and shrieks to come piercing through the darkness. Amidst such a calamity, the London Times hysterically predicted, Lincoln will rub his hands and think that revenge is sweet.

Lincolns response to all the criticism? Not a word. It is worth notingalthough Churchill, perhaps out of kindness, did notthat the failure of the American public to rally immediately round Lincolns greatest act may have been attributable at least in part to something very un-Churchillian, and for that matter un-Lincolnian as well: public silence. In fact, while most modern Americans justly regard his words as canonical, Lincoln remained similarly silent for most of his embattled presidency. His administration was more often characterized by the absence of words than by oratory. Understanding that largely forgotten historical reality makes this collection all the more precious, for it documents in a lively and accessible manner the ways Lincoln tested his creative gifts to communicate forcefully to the American public during the Civil War: through the power and publication of his writing, even if tradition required that his voice be stilled.

To be sure, Lincoln wrote to be heard by live audiences for most of his three-decade-long public career. Appropriately, this volume abounds with examples, though many originals do not survive in his own hand. (Lincoln did not bother to have his texts archived until he began employing private secretaries in 1860; until then, seeing his speeches in newspaper print was all that mattered to him.) Nonetheless, his surviving jottings and drafts, in increasingly neat penmanship over the years (quite the opposite of the indecipherable chicken-scratches over which researchers labor today) reveal a keen mind and a sure hand. On the following pages, we can almost imagine ourselves back in the nineteenth century, eavesdropping on Lincoln as his thoughts spilled over into words. He composed more than a million in all, though the highlights presented here will prove more than sufficient to testify to his creative genius and hard labor.

The influential stem-winders of the 1850s are of course still worth remembering: his long oration at Peoria, all but introducing the new anti-slavery Republican Party ()although, as they say, you had to be there. However lacerating his quick wit on the stump, Lincoln was never a great extemporaneous speaker, and the debates, famous as they have become in American political lore, brought out the best in neither the Republican nor Democratic candidates. Ingeniously, Lincoln made certain the flawed results would be remembered in spite of themselves, and would serve as a kind of personal platform two years later when he sought the presidencybecause by that time tradition forbade him from saying more. Ironically, the collection of debate transcriptsedited and engineered by Lincoln himselfbecame a bestseller just as their author went publicly mute. With rare exceptions, we sometimes forget, he remained so for the rest of his life, including his years in the White House. Thus the explanatory rhetoric he withheld from the Emancipation Proclamation was a rule, not an exception.

What makes Lincolns presidential communication particularly fascinatingand riveting examples abound in this collectionis that he wrote so much in the White House yet said so little. He had finally assumed a position of leadership from which to unleash his astonishing vocabulary and arresting style nationwide. But because the bully pulpit did not yet exist, the words he did issue remained largely unspoken. Chief executives of the day were expected to refrain from addressing their constituents publicly. Accordingly, Lincoln held no signing ceremony, gave no interviews, issued no additional statements, and made no speeches to explain, amplify, or herald the freedom document he knew would not only outrage some Americans and alter the rationale for the entire Civil War, but also make his name long endure in the annals of humankind. He merely ordered the Emancipation Proclamation published, and allowed its dry, legalistic prose to carry the weight of its history-altering message. To a voluble leader like Churchill, accustomed to leading with wordson the streets, at the House of Parliament, on the radioit must have been hard to understand, much less explain, how Lincolns most momentous decision had arrived on the American scene in almost stealthy silence. But sometimes the truth runs against the grain of myth.