Copyright page

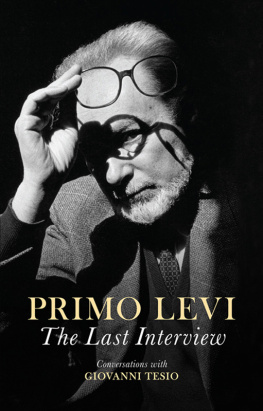

First published in Italian as Io che vi parlo. Conversazione con Giovanni Tesio Giulio Einaudi editore s.p.a, Turin, 2016

This English edition Polity Press, 2018

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1954-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1955-2 (pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Levi, Primo, author. | Tesio, Giovanni, 1946- interviewer.

Title: The last interview : conversation with Giovanni Tesio / Primo Levi.

Other titles: Lo che vi parlo. English

Description: Medford, MA : Polity, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017058561 (print) | LCCN 2017059366 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509519583 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509519545 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509519552 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Levi, PrimoInterviews. | Authors, Italian20th centuryInterviews. | Jewish authorsItalyInterviews. | Holocaust survivorsItalyInterviews.

Classification: LCC PQ4872.E8 (ebook) | LCC PQ4872.E8 Z4613 2018 (print) | DDC 858/.91409dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017058561

Typeset in 11 on 14 pt Sabon by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in the United Kingdom by Clays Ltd, St Ives PLC

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Introduction

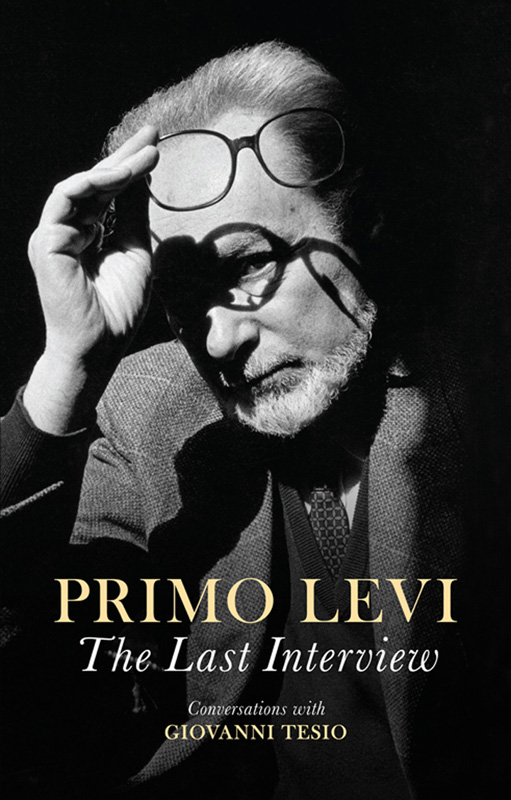

The conversations in this book were intended as material for an authorized biography, but they were also an act of kindness. The literary critic Giovanni Tesio had realized that his friend Primo Levi was suffering from severe depression which left him feeling unable to write, and thought that working together in this way might be consoling and even therapeutic. Consequently these transcriptions are in one sense an intimate record of life events shared with a friend, but in another and very important sense they enable us to overhear the words of a very reserved and private man who paradoxically used his own experiences as the basis for his greatest work.

There are good reasons for Levi's desire to keep his home life out of the public sphere. Turin, his native city, was proverbially reserved and respectful of the proprieties, and his upbringing there was a typically bourgeois one. For a young man from such a background, one of the most devastating aspects of the barbarities he suffered in Auschwitz was that, along with their clothes and their hair and even their names, prisoners were stripped of every last shred of privacy, a degrading and depersonalizing process which began in the cattle trucks, devoid of so much as a bucket, in which deportees were transported to brief slavery or immediate death. The impulse, as he shouldered the life-long task of bearing witness, to close the front door of 75 Corso Re Umberto on a protected space, must have been overwhelming. In addition, his growing international renown, which reached its peak with the English translation, in 1984, of The Periodic Table, meant that he came to be seen, much against his will, as some kind of guru or secular saint, whose Holocaust accounts were thought to represent not a grim and needed warning but a triumph of the human spirit. As he told Tesio, he felt gradually overwhelmed, first in Italy and then abroad, by this wave of success which has profoundly affected my equilibrium and put me in the shoes of someone I am not. From this, too, the private space with which he was able to surround himself at his writing desk, as he had earlier done at his laboratory bench in the Siva paint and varnish factory, offered a much-needed retreat.

While it was Auschwitz, from which he returned like Coleridge's Ancient Mariner, who waylays on the street the wedding guests going to the feast, inflicting on them the story of his misfortune, which first compelled him to write about what he had suffered, observed and, exceptionally, survived, Levi was also to become a witness of a very different kind, attempting with considerable success to bridge the needless gulf which separates the so-called two cultures with dispatches from the world of pure and applied chemistry. This book should be read alongside The Periodic Table, to which it adds valuable background material about his schooldays and his emotional life as a young man, but to understand why sharing the pleasures and pains of a chemist's trade was so important to Levi, it is necessary to go into a little detail about the educational system in Italy during the Fascist period.

It is well known that Levi narrowly escaped being excluded from a university education by the passing of the anti-Semitic racial laws, and was prevented by them from going on to the academic career which, as a student who had graduated with top marks and distinction, would otherwise have been open to him. However, the frustration he felt as a schoolboy, with the narrowly arts-based curriculum which forced him to discover science through his own reading and his experiments with household chemicals, was also due to Fascist policy. As Martin Clark explains, the Fascists inherited a three-stream system of secondary education: the ginnasio and liceo [lower and higher secondary schools] for the social lite, the technical schools and technical institutes for the commercial middle classes, and the scuole normali for girls wanting to become primary teachers The Fascists soon changed all that. In 1923, Giovanni Gentile, as minister of education, reorganized secondary education. Under these reforms, initiated as they were by an idealist philosopher, the old technical schools were abolished and access to, and the status of, the technical institutes was greatly reduced, as was admission to the university science faculties. One curious effect of this reorganization was that Latin, Italian, History and Philosophy were taught by men, whereas Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry continued to be taught by women. This was an apt comment on Fascist male chauvinism, and it is an apt comment too on how the subjects which mattered most to Levi were now regarded. Another effect was that Italy produced fewer engineers, scientists and doctors in the late 1930s than the early 1920s.

However, the most significant and moving revelation in The Last Interview does not concern either education or chemistry. Although Tesio suggests in his preface, I knew Primo Levi, that the real difference in our conversations, as compared with other interviews, was more in the tone than the content, in one painful respect Levi confided something to him which stitches together the repeated but oblique references throughout his writing to a woman who was dear to my heart who had been deported to Auschwitz with him. and was tormented by the irrational but inevitable feeling that if only he had acted differently perhaps he and she might have been elsewhere when their partisan band was rounded up. It was a really desperate situation for me, being in love with someone who was gone and, what's more, whose death one had caused, and I think that what one feels is Perhaps if I had been less inhibited with her, if we had run away together, if we had made love I was incapable of those things.

Next page