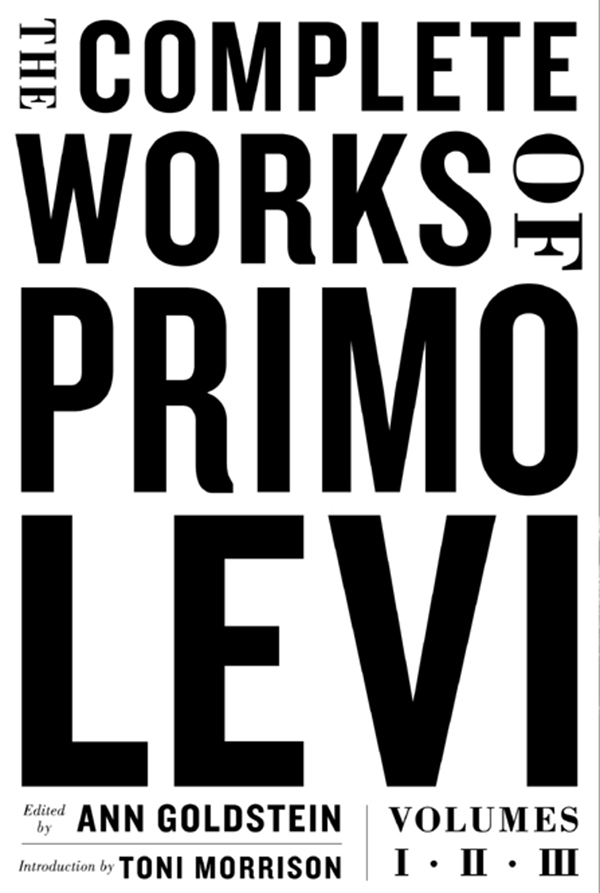

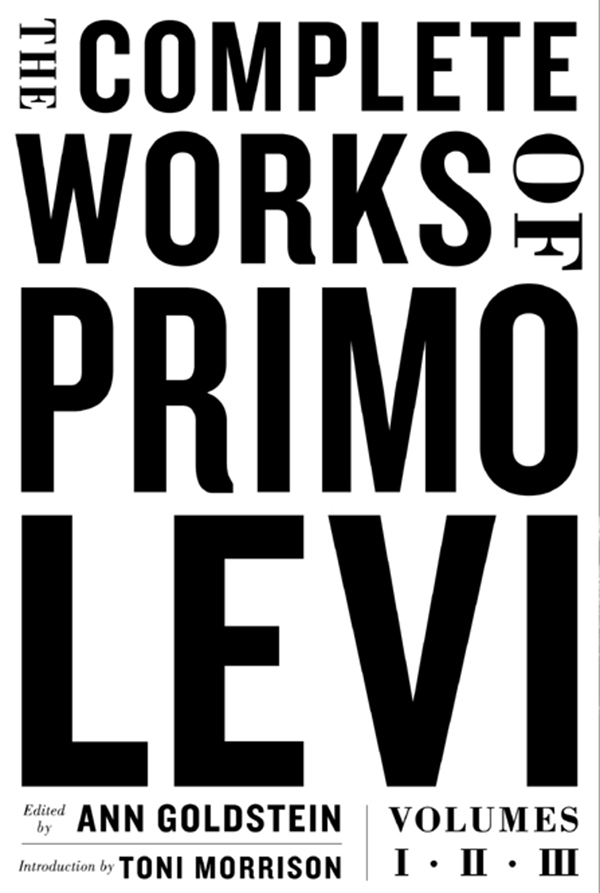

The Complete Works of

Primo Levi

This book has been published with a translation grant awarded by the

Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Published by arrangement with Giulio Einaudi Editore

Copyright 2015 by Liveright Publishing Corporation

Introduction copyright 2015 by Toni Morrison

Translators Afterword by Stuart Woolf copyright 2015 by Stuart Woolf

Primo Levi in America copyright 2015 by Robert Weil

Chronology, maps of places relevant to Primo Levi in Turin and Piedmont,

The Publication of Primo Levis Works in the World, Notes on the Texts,

and Select Bibliography copyright 2014 by Centro Internazionale

di Studi Primo Levi, Torino, Italy. All rights reserved.

All rights reserved

If This Is a Man by Primo Levi, translated by Stuart Woolf. Copyright 1958 by Giulio

Einaudi Editore s.p.a. Published by arrangement with Viking Penguin,

an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

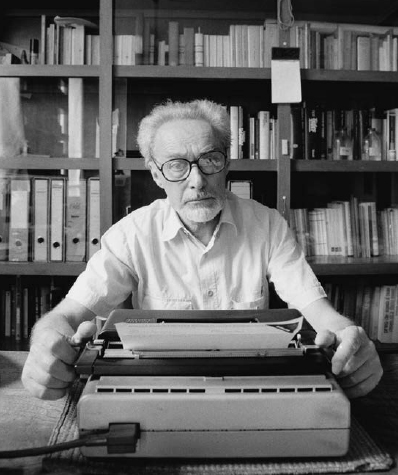

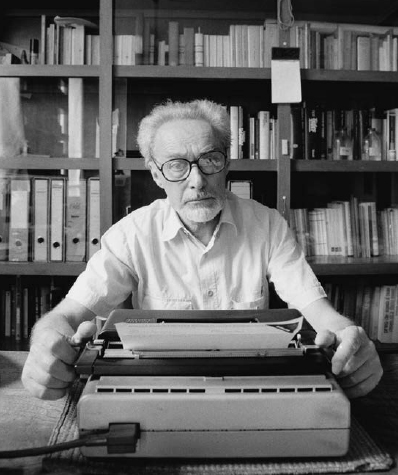

Frontispiece photograph copyright by Gianni Giansanti / Sygma/Corbis

Since this page cannot legibly accomodate all the copyright notices, pages 28992901

constitute an extension of the copyright page.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation,

a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Ellen Cipriano

Production manager: Anna Oler

ISBN 978-0-87140-456-5

ISBN 978-1-63149-206-8 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

CONTENTS

Introduction

Toni Morrison

Editors Introduction

Ann Goldstein

Chronology

Ernesto Ferrero

1.IF THIS IS A MAN

Translated by Stuart Woolf

2.THE TRUCE

Translated by Ann Goldstein

3.NATURAL HISTORIES

Translated by Jenny McPhee

4.FLAW OF FORM

Translated by Jenny McPhee

5.THE PERIODIC TABLE

Translated by Ann Goldstein

6.THE WRENCH

Translated by Nathaniel Rich

7.UNCOLLECTED STORIES AND ESSAYS: 19491980

Translated by Alessandra Bastagli and Francesco Bastagli

8.LILITH AND OTHER STORIES

Translated by Ann Goldstein

9.IF NOT NOW, WHEN?

Translated by Antony Shugaar

10.COLLECTED POEMS

Translated by Jonathan Galassi

11.OTHER PEOPLES TRADES

Translated by Antony Shugaar

12.STORIES AND ESSAYS

Translated by Anne Milano Appel

13.THE DROWNED AND THE SAVED

Translated by Michael F. Moore

14.UNCOLLECTED STORIES AND ESSAYS: 19811987

Translated by Alessandra Bastagli and Francesco Bastagli

Primo Levi in America

Robert Weil

The Publication of Primo Levis Works in the World

Monica Quirico

Notes on the Texts

Domenico Scarpa

Select Bibliography

Domenico Scarpa

T he Complete Works of Primo Levi is far more than a welcome opportunity to reevaluate and reexamine historical and contemporary plagues of systematic necrology; it becomes a brilliant deconstruction of malign forces. The triumph of human identity and worth over the pathology of human destruction glows virtually everywhere in Levis writing. For a number of reasons his works are singular amid the wealth of Holocaust literature.

First, for me, is his languageinfused as it is with references to and intimate knowledge of ancient and modern sources of philosophy, poetry, and the figurative uses of scientific knowledge. Virgil, Homer, Eliot, Dante, Rilke play useful roles in his efforts to understand the life he lived in the concentration camp, as does his deep knowledge of science. Everything Levi knows he puts to use. Ungraspable as the necrotic impulse is, the necessity to tell, to describe the monotonous horror of the mud, is vital as he speaks for and of the throngs who died in vain. Language is the gold he mines to counter the hopelessness of meaningful communication between prisoners and guards. A pointed example of that hopelessness is the exchange, recounted in If This Is a Man, between himself and a guard when he breaks off an icicle to soothe his thirst. The guard snatches it from his hand. When Levi asks Why? the guard answers, There is no why here. While the oppressors rely on sarcasm laced with cruelty, the prisoners employ looks, glances, facial expressions for clarity and meaning. Although photographs of troughs of corpses stun viewers with the scale of ruthlessness, it is language that seals and reclaims the singularity of human existence. Yet the response to visual images collapses before languageits stretch and depth can be more revelatory than the personal experience itself.

Everywhere in the language of this collection is the deliberate and sustained glorification of the human. Long after his eleven months in what he calls the Lager (Auschwitz III), as a survivor, Primo Levi understands evil as not only banal but unworthy of our insighteven of our intelligence, for it reveals nothing interesting or compelling about itself. It has merely size to solicit our attention and an alien stench to repel or impress us. For this articulate survivor, individual identity is supreme; efforts to drown identity inevitably become futile. He refuses to place cruel and witless slaughter on a pedestal of fascination or to locate in it any serious meaning. His primary focus is ethics.

His disdain for necrology is legend. Dwelling on memorieshis and othersof survival rather than on the monstrous detritus of suffering, he is compelled by how suffering is borne whatever its consequence. Time and time again we are moved by his narratives of how men refuse erasure.

Melancholy and sorrow often reside more in his poetry than in his prose. There we find insects, accusatory ghosts, and the sadness of place. In two of his poems, Song of the Crow I and Song of the Crow II, desolation is an inner reality monitored by a malevolent companion.

In the first, memory and sorrow are fixed and eternal.

Ive come from very far away

To bring bad news.

...............

To find your window,

To find your ear,

To bring you the sad news

To take the joy from your sleep,

To spoil your bread and wine,

To sit in your heart each evening.

The second Song of the Crow is even more resonant of despair.

What is the number of your days? Ive counted them:

Few and brief, and each one heavy with cares;

With anguish about the inevitable night,

When nothing saves you from yourself;

With fear of the dawn that follows,

With waiting for me, who wait for you,

With me who (hopeless, hopeless to escape!)

Will chase you to the ends of the earth,

Riding your horse,

Darkening the bridge of your ship

With my little black shadow,

Sitting at the table where you sit,

Certain guest at every haven,

Sure companion of your every rest.

Next page