Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Any piece of historical research, individual and solitary as it may be, is always a group project. And thus I would like to thank all those who assisted in making this book come to life, none of whom are of course in any way responsible for whatever may be arguable in the final product.

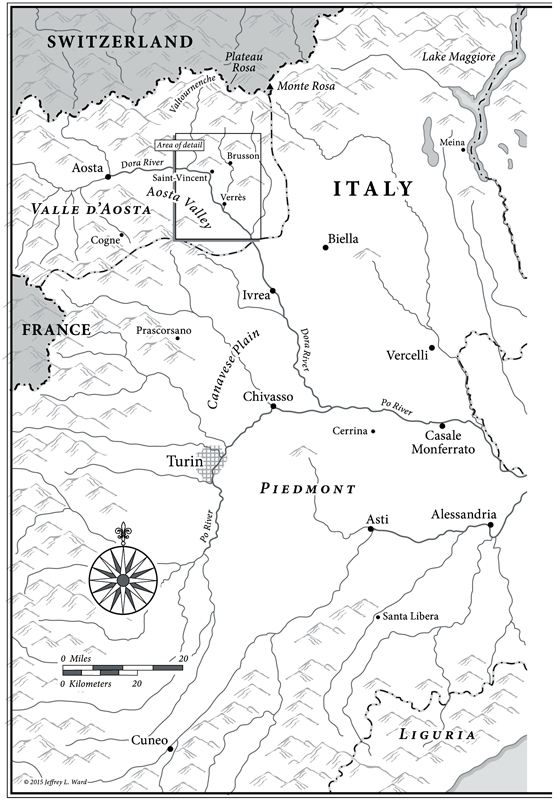

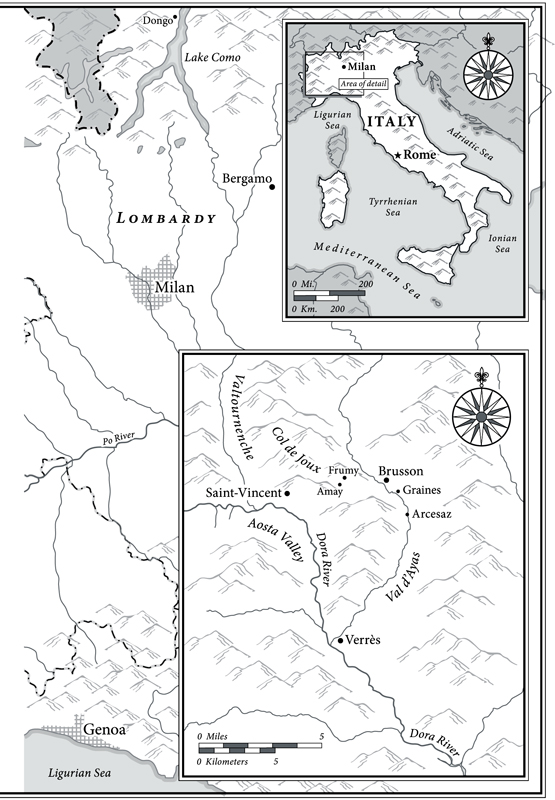

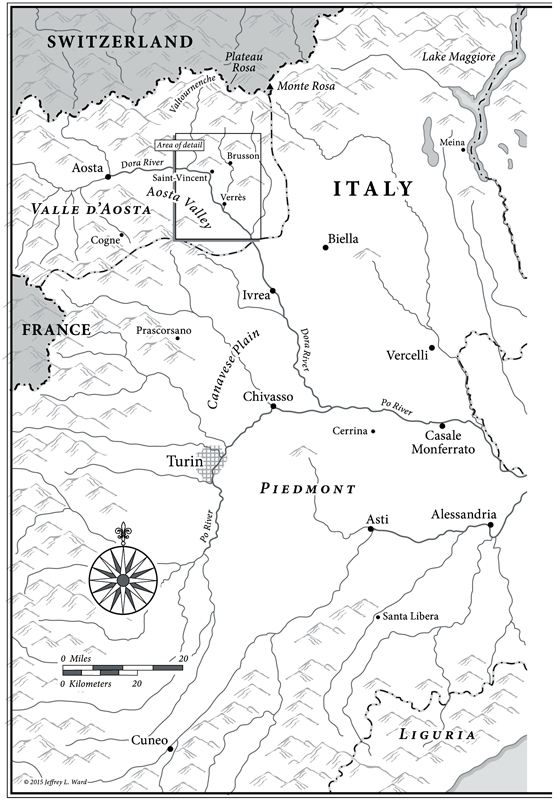

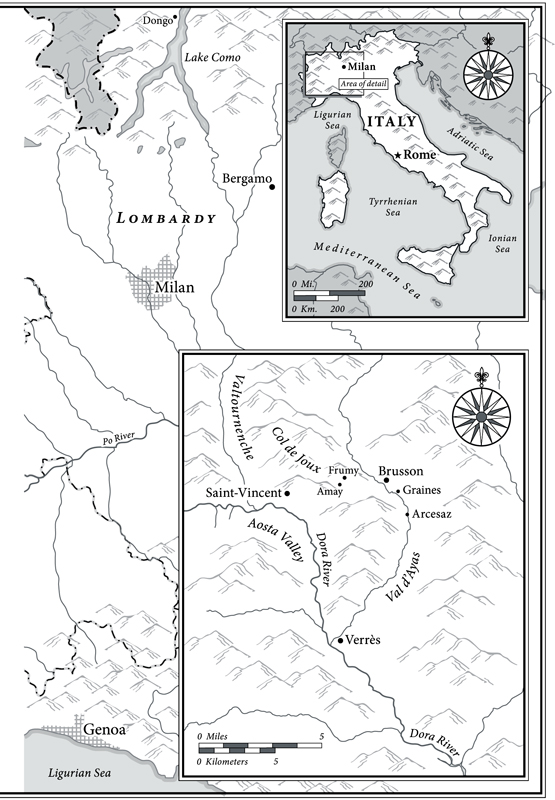

In Aosta, Silvana Presa guided me on my first steps into the Resistance in Valle dAosta. In Turin, I benefited from the help of the Istituto storico della Resistenza and of the Centro internazionale di studi Primo Levi. In Casale Monferrato, Sergio Favretto and Fabrizio Meni were both speedy and thoughtful in helping me find my way. At the Centro di documentazione ebraica contemporanea in Milan, Liliana Picciotto and her team were unusually solicitous. In London, Ian Thomson guided me in finding sources at the Weiner Library. Special thanks are due to Roberta Cairoli, whose scholarly generosity allowed me to consult papers from the National Archives in Washington. This book also owes much to the actors in this story and their descendants, who opened the doors of their homes, consulted their memories, and shared personal and family documents with me. My thanks to Yves Francisco, Simonetta Bachi, and Aldo Piacenza; to Corrado Calvi and Chiara Cane, who also made it possible for me to meet Angelo Brignoglio, Maria Cerruti, Teresa Mazzucco, and Renato Porta; and to Andrea and Davide Zabaldano, who after our first meeting agreed to accompany me a ways down the road.

Three colleaguesthree friendsread the first draft of this book and discussed it with me at length. They disagreed with certain passages, critiqued the text in detail and as a whole, and offered counsel on both form and substance. My thanks to Walter Barberis, Enrica Bricchetto, and Domenico Scarpa, who were tremendously helpful in making this book better.

Rosaria Carpinelli has been more than a literary agent. In the beginning, she helped me find a tone that I hope my readers will feel is the right one; later, she helped me find the right publisher. At Mondadori, Francesco Anzelmo was quick to recognize the books defects as well as its merits, and if in the end it is found worthy, much of the credit goes to him.

Finally, as was the case with my two previous books, The Body of Il Duce and Padre Pio , the American edition of this book has profited from exceptional assistance on the Metropolitan side. Frederika Randalls translation is infused not only with the historical knowledge she has gained as an adopted Italian but with all her literary sensibility. Grigory Tovbis rightly insisted, above all, on what the Anglophone reader needed to know in order to understand the story. And Sara Bershtel once more had faith in me and in what I believe is important to pass on from Italys twentieth-century history. My heartfelt thanks to all three.

On July 25, 1943, Mussolini was suddenly and bloodlessly ousted during a meeting of the Grand Council of Fascism, his own governing body. The war was generally unpopular in Italy by that point, and it was also going badly. After a bloody campaign in Russia and defeat at El Alamein in North Africa, Italys army was ill supplied, exhausted, and had suffered many losses. Two weeks before, the Allies had landed in Sicily, driving the Germans north.

Il Duce was spirited away, and after some peregrinations ended up on the remote heights of the Gran Sasso plateau in Abruzzo, at a place that could only be reached by air or cable car. King Victor Emmanuel III appointed Marshal Pietro Badoglio as head of government to replace Mussolini. On September 8, Badoglio surrendered to the Allies. Italy was no longer Hitlers ally.

Badoglio announced the armistice by saying that all acts of hostility against Anglo-American forces on the part of Italian forces everywhere must immediately cease. Given these stark counterorders from one day to the next, Italian soldierssome 350,000 were stationed in France, Greece, Yugoslavia, and Albaniasuddenly had to provide for their own defense, deployed as they often were alongside the Germans. The soldiers of the Wehrmacht had been their allies until the day before, but now the Italians were suddenly exposed to reprisals or deportation to Germany. Some would join the resistance in the Balkans. The rest had to find their way home by their own means. Meanwhile Allied prisoners of war in Italy were abruptly, if briefly, free to leave their prison camps.

The very day of the armistice, September 8, the Germans began invading northern Italy. Two days later, in central Italy, they had taken Rome. The king and Badoglio boarded a ship at Pescara, on the Adriatic, and sailed to Brindisi in the south, a safe area controlled by the Allies. There, in the Southern Kingdom under the Allied wing, Badoglio declared war on Germany and fought along with the Allies. He would remain prime minister of the armistice government until 1944.

Meanwhile, on September 12, the Germans made a daring air raid on Mussolinis place of confinement on the Gran Sasso plateau and carried him off. Il Duce became leader of the Italian Social Republic, an only nominally independent state based in the German-occupied portion of Italy. Mussolinis headquarters during 194345 were at Sal, a town on Lake Garda; thus the second Fascist regime is often called the Republic of Sal.

When the Italian Social Republic was proclaimed on September 23, 1943, Italians in the north and center of the country not only faced a foreign invaderthe Germansbut also had to choose whether to side with the Republic of Sal or fight for a free Italy against what was officially their own government. There was the patriotic war of liberation, a battle to oust the foreign invader and disarm its local pawn. But there was as well another aspect to the struggle. That second strain would become known as Italys civil war, an all-out conflict in which Italians of the Resistance fought to wrest the country not just from its immediate occupiers but from the Italians who for twenty years had embodied Fascist rule.

The war of liberation and the civil war often coincided in the same battles. But the partisans were fighting two enemies, not one. The conflict was all the more sharp and cruel because one side was made up of army regulars and the other of largely untrained guerrilla rebels, however well-organized militarily they would become by the end of the war.

The civil war demanded that Italians make a choice. And even today, many Italians have not forgotten who took which side. There was nothing automatic about any one persons allegiance; after all, Italy had been an Axis partner until September 8. The moment of decision for many young Italians at home came when the Republic of Sal issued conscription orders in November 1943, backed up by harsh punishments. To join the Sal army, or run away to the hills? That was the question in the autumn and winter of 1943. And these became the months of what Primo Levi would call inventing the Resistance.