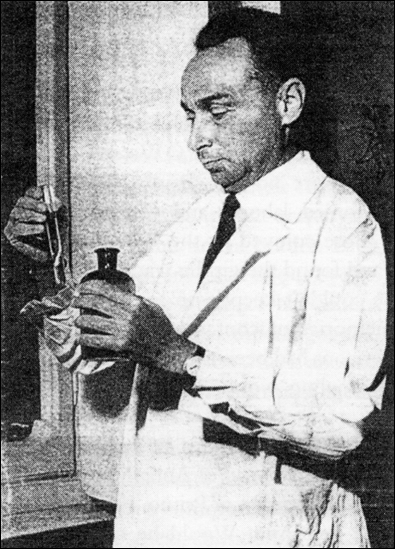

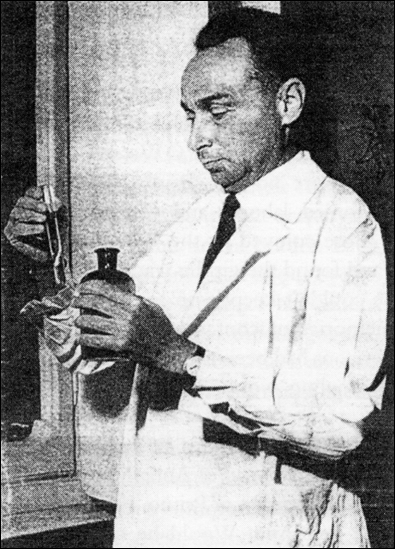

PRIMO LEVI

Primo Levi

The Matter of a Life

BEREL LANG

Copyright 2013 by Berel Lang.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations,

in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S.

Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written

permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational,

business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu

(U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by Integrated Publishing Solutions,

Grand Rapids, Michigan. Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lang, Berel.

Primo Levi : the matter of a life / Berel Lang.

pages cm. (Jewish Lives)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-13723-1 (alk. paper)

1. Levi, Primo. 2. JewsItalyBiography. 3. Holocaust

survivorsItalyBiography. I. Title.

PQ4872.E8Z724 2013

853.914dc23

[B]

2013018411

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I tried to explain... that the nobility of Man lay in

making himself the conqueror of matter, and [that] I wanted

to remain faithful to this nobility. That conquering matter is

to understand it, and understanding matter is necessary

to understanding the universe and ourselves.

_____________________

Chemistry led to the heart of Matter, and Matter

was our ally precisely because the Spirit,

dear to Fascism, was

our enemy.

Primo Levi

Books by Berel Lang

Art and Inquiry

The Human Bestiary

Philosophy and the Art of Writing

Act and Idea in the Nazi Genocide

The Anatomy of Philosophical Style

Writing and the Moral Self

Minds Bodies: Thought in the Act

Heideggers Silence

The Future of the Holocaust

Holocaust Representation: Art Within the Limits of History and Ethics

Post-Holocaust: Interpretation, Misinterpretation, and the Claims of History

Philosophical Witnessing: The Holocaust as Presence

Edited/Co-edited Volumes

Marxism and Art

The Concept of Style

Philosophical Style

The Philosopher in the Community

The Death of Art

Writing and the Holocaust

Race and Racism in Theory and Practice

Method and Truth

The Holocaust: A Reader

For Barbara Estrin

Interlocutor: But surely, M. Godard, you would agree that every film should have a beginning, a middle and an end.

M. Godard: Yes, of coursebut not necessarily in that order.

CONTENTS

PRIMO LEVI

1

The End

It is particularly difficult to understand why a

person kills himself, since generally speaking the

suicide himself is not fully aware.

Primo Levi, Jean Amry, Philosopher and

Suicide, La Stampa, December 7, 1978

ON JULY 31, 1987, Primo Levi would have turned sixty-eight, but he had died three and a half months earlier, on April 11, in the same apartment building on Turins Corso Re Umberto where he was born and where, except for two intervals, he had lived continuously since. One of those intervals was related to jobs he took after completing his university studies in chemistry in 1941, work that took him to Milan. After that came the two-year period that included his time with the partisans and capture by the Italian Fascists, eleven months as a Hftling (prisoner) in Auschwitz, and his lengthy post-liberation return to Turin. The physician called by police to the scene of his death termed it a suicide, and that verdict was later affirmed by a Turin court. The cause of death was judged to be a fall from the landing of Levis apartment on the third floor (the fourth, in American count) to the ground floor about fifty feet below. There was no evidence of criminal responsibility, and there were no eyewitnesses. The verdict of suicide was thus an inference, opening space for speculation that quickly filled with dissentopposition to the verdict on one side and, on the other, disagreement among those who accepted the verdict but disputed the acts causes. Both responses led to pronouncements on Levis life as much as on his death.

In Levis closest circle of family and friends, reaction to his suicide mingled shock and grief with an awareness that approached resignation. A number of intimates had anticipated that end; the depression they saw engulfing him in the months previous was deep and sustained, even if not unbroken. Levi himself spoke and wrote about his depression, variously naming the factors that he saw contributing to it. Among these: Levis mother, Rina (Ester), aged ninety-one and owner of the family apartmenta gift to her upon her wedding to which Levi and his wife, Lucia, had temporarily moved soon after their marriagehad been paralyzed for nine months by a stroke. In uncertain health for years before this, she increasingly demanded his presence in addition to that of hired aides (she would outlive her son by four years). Levis mother-in-law, Beatrice Morpurgo, who lived in an apartment within walking distance, was ninety-five and had been virtually blind for fifteen years, requiring Lucias continued attention. Levi had recently begun to consider moving his mother to a nursing home, but his sense of obligation resisted the change, with Lucia adding her objections to it. (Agnese Incisa, an editor at Einaudi and a friend of Levis, had reproved him, Either you die or your mother dies a locution he would himself later repeat.) The strain of these

To these external factors, Levis body in 1987 added its own weight. Foot ulcers, perhaps vestigial from Auschwitz where he first experienced them, reappeared; shingles that surfaced first in 1978 now recurred. In mid-February, he underwent surgery for an enlarged prostate, and on March 18, the complication of a bladder blockage required further surgery (again under general anesthesia) and ten additional days in the hospital. There is some question of whether there were two operations or one, but none about the problem itself. No evidence of cancer was found in these procedures, but Levi remained apprehensive; in the aftermath he mentioned a problem with incontinence a common effect of prostate surgery, but distressing nonetheless. Beyond such specific challenges, Levi had begun to fear that his memory and powers of concentration were failing, the remarkable faculties on which his work and expressive presence had drawn so readily. And then, too, there was a history of depression itself which extended to pre-Auschwitz days and only underscored the severity of this newest appearance. The regular pattern found in depressions of building on their own impetus added its increments here in his last days as well; the variety of anti-depressant drugs to which Levi turned seemed increasingly ineffective and all the more frustrating because of that.

Such factors would have had different weights, but their collective impact cannot be doubted: individual issues among them might have sufficed as causes or reasons for suicideif there is indeed any way of generalizing about that. Levis younger sister, Anna Maria, would insist after his death that the assembly of possibilities could be reduced entirely to one, namely, the prostate operation and its consequence. In any event, to recognize the cumulative effect of the factors noted does not diminish the challenge each posed individually.

Next page