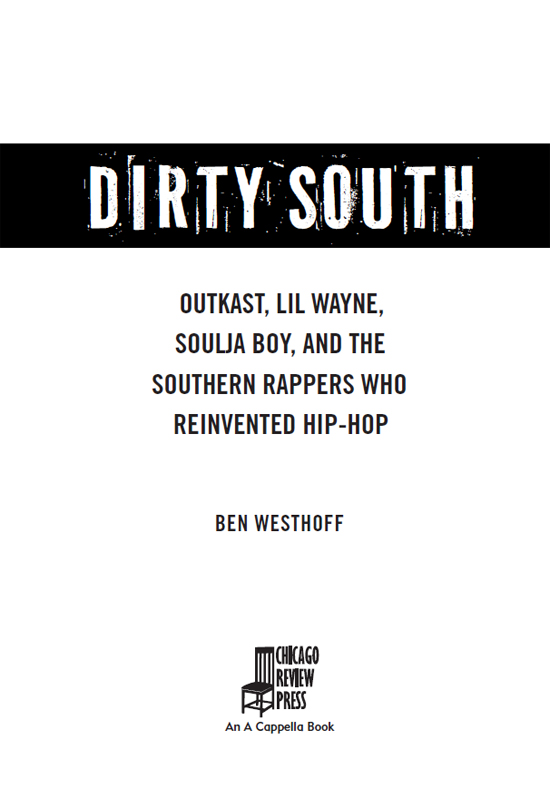

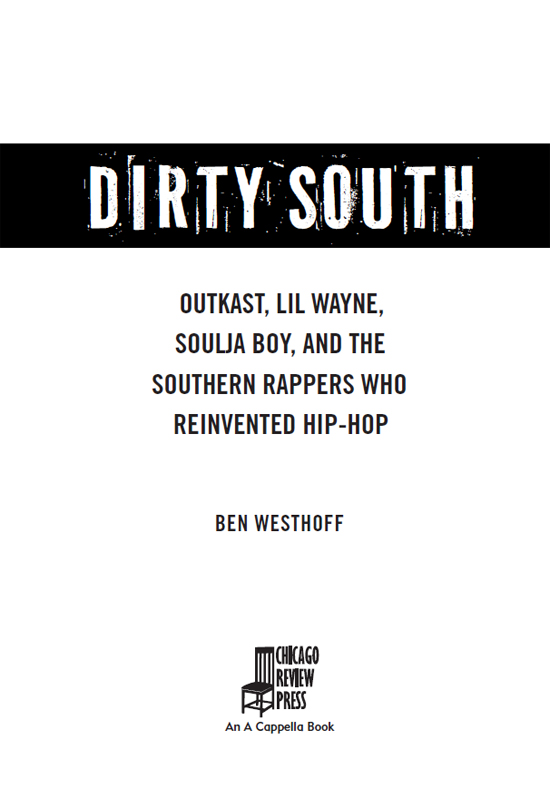

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Westhoff, Ben.

Dirty South : Outkast, Lil Wayne, Soulja Boy, and the Southern rappers who reinvented hip-hop / Ben Westhoff.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56976-606-4 (pbk.)

1. Rap (Music)Southern StatesHistory and criticism. 2. Rap musiciansSouthern States. I. Title.

ML3531.W47 2011

782.4216490975dc22

2010053907

Cover and interior design: Jonathan Hahn

Cover photograph: Howard Huang/Contour by Getty Images

Portions of this book originally appeared in the Village Voice, the Houston Press, the Dallas Observer, Miami New Times, and New Times Broward-Palm Beach, which are all part of the Village Voice Media Holdings family of companies. They appear here with the kind permission of VVMH. Other portions originally appeared in Creative Loafing publications.

2011 by Ben Westhoff

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-56976-606-4

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

To Anna B and her curls

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

MS. PEACHEZ favors bright clown wigs, press-on nails, and pastel blouses over her beefy, middle-aged frame. In the video for her 2006 song, Fry That Chicken, she raps in a voice deeper than my uncle Johns. The fact that she is a man is just one of many things that are odd about Fry That Chicken.

Like many immediately catchy songs, its so dumb its genius. Something of a nursery rhyme crossed with a Mardi Gras march, its springy bass propels the beat along while high-register synth notes chime like Pavlovs bell. I got a pan, and I got a plan/ Ima fry this chicken in my hand! she raps. Everybody want a piece of my chicken/ Southern fried chicken/ Finger lickin.

Its low-budget video takes place in the yard of a rural shack, surrounded by chicken coops. The scene is a good ol country barbeque, with Ms. Peachez holding raw chickens and taunting a group of hungry grade-school children. Peachezs blue hair, and her T-shirt bearing an oversized peach, are nearly consumed by smoke from the grill, which heats a giant pan of bubbling, waiting grease. She passes thighs and legs through a bowl of flour, massaging them with her hands in time to the beat. After dropping the segments into the pan, she shakes her hips and gets the hot sauce ready.

Fry that chicken! the kids demand, looking half-crazed as they pound on the picnic table and wave their arms. Peachez advises the kids to wash their hands, Cause youre gon be lickin em! When the food is ready the kids tear into it, eating with their fingers and then, yes, licking them.

Theres something innocent and funny about the video, and the song has a way of worming its way into your head. But theres also something creepy. It vaguely recalls a nineteenth-century blackface skit, although none of the participants are white, and the production appears to have been made in earnest, rather than as an ironic joke.

But a jive-talking, cartoonish drag queen hypnotizing a group of children with her southern-fried bird, seriously? Could the videos crafters possibly be unaware of its loaded stereotypes?

The oddness of the clip has been eclipsed only by its popularity. Its been seen 3.6 million times, and still gets thousands of views per day. But as Fry That Chicken went viral, it somehow became one of the most politicized hip-hop documents in years. To many, it epitomized the troubling turn rap music was taking. Despite the fact that bloggers and other Internet commentators knew nothing about Ms. Peachezshe didnt have a record deal and had never done an interviewthey called her a degrading minstrel act that would set the civil rights movement back thirty years.

Even the Washington Post weighed in. Op-ed columnist Jabari Asim decried the antics of this Aunt Jemima off her meds, whose video engagesno, embracesracial stereotypes. Yes, it is the stuff of nightmares, he asserted. He added that it reminded him of a scene from D. W. Griffiths 1915 movie The Birth of a Nation, the granddaddy of American racial propaganda films, which warned of a Negro coup detat and glorified the Ku Klux Klan.

Maybe Ive seen Birth of a Nation too many times, but it suddenly seemed mild when compared to Fry That Chicken, Asim wrote, adding, How can anyone explain black performers willinglyand apparently joyfullyperpetuating such foolishness in the 21st century?

Such criticism only seemed to spur Peachezs popularity, and she proceeded to release a series of follow-ups, each more outlandish than the last. Two and a half million more people watched her In the Tub video, a loose parody of 50 Cents In da Club. It finds her playing with rubber duckies and washing her bootie in an outdoor washbasin, her broad shoulders and flat chest exposed.

The most provocative in the series had to be From da Country, which opens with a nearly toothless midget named Uncle Shorty, who wears a curly blond wig and chows down on some watermelon. Theres a guy in a chicken suit, tractors, and Ms. Peachez showing off a plate of candied yams swarming with flies. Meanwhile, kids perform steps with names like The Neck Bone, The Corn Bread, and The Collard Greens.

HIP-HOP started in the Bronx, was dominated by New Yorkers in the 1980s, and felt its center of gravity pulled toward the West Coast the next decade, through the success of gangsta rap acts like N.W.A.

As southern rap gained popularity in the 2000s, fans of true hip-hop said it appealed to our most base, childish instincts. Nursery rhyme jingles, they claimed, would be the downfall of an art form that has evolved from the good-time rhymes of the Sugarhill Gang three decades ago to the enlightened compositions of Nas. By the mid-aughts this chorus reached a fever pitch.

The problem wasnt just Ms. Peachez, who was presumed to be southern. There were plenty of other rappers to complain about, the ones responsible for the stripped-down, shucking-and-jiving ditties that were taking over the radio. These were minstrel show MCs, an epithet pegged to crunk artists like Lil Jon, who had a mouth full of platinum and carried around a pimp chalice.

But crunk was fading, and so the culprits became a new crop of young, blinged-out rappers whose songs often instructed listeners to do a new dance. These included Atlanta rapper Young Dro, whose hit Shoulder Lean told you to bounce right to left and let your shoulder lean, and whose video features an older man dumping a bag of sugar directly into his pitcher of red Kool-Aid.

Then there was Atlanta group D4L (Down for Life), whose ubiquitous radio jam Laffy Taffy sounded mined from the presets of a childs mini Casio, only not so complex. The song uses the wax-paper-wrapped confection of the title as a metaphor for a bulbous rear end. Im lookin fo Mrs. Bubble Gum/ Im Mr. Chick-O-Stick/ I wanna dun dun dunt/ Cause you so thick... Shake that laffy taffy.

Teenage Saint Louis rapper Jibbs earned his spot in this group for Chain Hang Low, another massive hit that was an ode to his diamond pendant. The track borrows its singsong melody from the 1830s-era folk song Zip Coon, which is also known as Turkey in the Straw and the ice cream truck jingle.

Do your chain hang low?

Do it wobble to the floor?

Do it shine in the light?

Is it platinum, is it gold?

Critics argued that these artistsand their complicit record labelswere indulging in the worst black stereotypes for the entertainment of white people. Record labels are rushing out to sign the most coon-like negros they can find, declared popular hip-hop blogger Byron Crawford. Despite the fact that not all of the minstrel rappers were from the South, he insisted that the subgenre obviously has its origins in shitty southern hip-hop.

Next page