Copyright 2011 by Ian OConnor

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

OConnor, Ian.

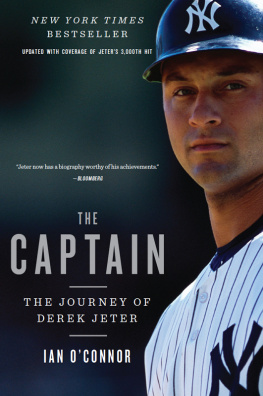

The captain: the journey of Derek Jeter / Ian OConnor.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-547-32793-8

ISBN 978-0-547-74760-6 (pbk.)

1. Jeter, Derek, date. 2. Baseball playersUnited StatesBiography. 3. New York Yankees (Baseball team) I. Title.

GV 865. J 48 O 37 2011

796.357092dc22

[B]

2010049772

Jacket design by Brian Moore

Jacket photograph Ron J. Berard/Corbis

e ISBN 978-0-547-54906-4

v3.0615

To Tracey,

my life, my love, and my inspiration

To Kyle,

my best friend, and my all-time favorite middle infielder

To Mr. David,

the first coach who gave me the ball

Introduction

On Monday afternoon, July 6, 2009, more than 46,000 sun-splashed baseball fans inside the new Yankee Stadium witnessed something they never imagined they would see.

Derek Jeter getting in an umpires face.

The captain of the New York Yankees had just made a wretched baserunning choiceanother shock to the extended holiday weekend crowdwhen he tried and failed to steal third with no outs in the first inning. The throw from Toronto Blue Jays catcher Rod Barajas to Scott Rolen arrived early enough for Rolen to recite the Greek alphabet before applying the tag.

Only Jeter being Jeter, he delivered the Toronto third baseman a lesson in resourcefulness right there in the infield dirt. The shortstop went in headfirst and used a Michael Phelps butterfly stroke to reach his arms around Rolens glove and touch the base untagged.

Marty Foster, veteran ump, did what everyone expected him to do. He saw the ball beat Jeter by a country mile, saw Rolen drop his glove in front of the bag, and sent the foolish runner back to his dugout and his stunned manager, Joe Girardi.

But for once, Jeter did not retreat to the dugout. He told Foster he had reached the base before he was tagged, and according to the shortstop, Foster responded, The ball beat you. He doesnt have to tag you.

The captain was incredulous. He doesnt have to tag you?

I was unaware of that change in the rule, Jeter would say.

As the ultimate guy who played the game the right way, Jeter felt a rare rush of anger rising from his toes. He marched toward Foster in search of a more acceptable answer, and the Yankees third-base coach, Rob Thomson, had to get between them. Girardi raced out to ensure Jeter did not earn the first ejection of his life, dating back to Little League, and the manager ended up getting tossed himself.

John Hirschbeck, crew chief, watched this scene unfold and said to himself what every living, breathing witness was thinking: Wow, thats unusual. Jeter would rather get swept by the Boston Red Sox than show up an ump.

But more unusual would be the postgame conversation inside the umpires room, where Hirschbeck held court with reporters while acting as a human shield for Foster, who showered and dressed behind a closed door. Thirteen years earlier, Hirschbeck had gotten up close and personal with ballplayer misconduct when Roberto Alomar spat in his face.

Like cops, umpires often adhere to a blue wall of silence. They have little choice but to protect each other. With players and managers emboldened by lavish guaranteed contracts, and with instant replay making infallible judges and juries out of millions of viewers, umpires are under siege from all corners. They are imperfect men burdened by the high-def, high-stakes demand for perfection.

And yet despite these truths, Hirschbeck faced the reporters gathered around him like campers around a fire and suggested he believed Jeters account.

In my twenty-seven years in the big leagues, the crew chief said, [Jeter] is probably the classiest person Ive ever been around.

Never mind that a day later, Foster would assure Hirschbeck he never told Jeter he did not need to be tagged (a claim Jeter vehemently denied, maintaining, He knows exactly what he said). Never mind that Hirschbeck heard Fosters version of what was said to the shortstop (The ball beat you, and I had him tagging you) and decided even the classiest of players might have misheard something in the heat of the moment.

The crew chiefs first instinct was to believe Jeters version of the truth. It would make his actions seem appropriate if thats what he was told, Hirschbeck said.

Yes, that was Derek Jeter in a nutshell: even an umpire would deem his inappropriate actions appropriate.

Months later, at a banquet announcing his son as Sports Illustrateds 2009 Sportsman of the Year, Charles Jeter spoke for his wife, Dot, when he told the crowd, One of the things thats really special for us is the fact that sometimes when were traveling, people might come up to us and they often say, You know, Im not a Yankee fan. But you know something? Your son has class and plays hard and we really respect what hes all about.

In the end, this is why millions of young ballplayers around America ask their coaches to assign them jersey number 2. Jeter does not embarrass the umpires or his coaches or his teammates or himself. His common acts of decency have made him the most respected and beloved figure in the game.

Funny, but Jeter never hit 25 home runs in a season. He never won a batting title. Never won a Most Valuable Player award.

But Jeter did win championships and a place in any debate over the greatest all-around shortstop of all time. He also won the title of patron saint of clean players in an era defined by performance-enhancing drugs.

When I told him in the spring of 2009 that I would be writing a book about his career, Jeter immediately replied, My careers not over. I explained my goalto author a defining work on his time with the Yankees as he was about to become the first member of the worlds most famous ball team to collect 3,000 hits.

Jeter decided against making major contributions to this book, in part because he did not want fans to think he was basking in his own glory while there were still grounders to run out and titles to win. He had other reasons, Im sure, but Jeter did agree to take some questions from me at his locker during the 2009 season.

For the record, this is my book, not his. It is a book shaped by more than two hundred interviews I conducted with Jeters teammates, friends, coaches, opponents, associates, employers, teachers, admirers, and detractors (his detractors were actually admirers willing to address what they perceived as Jeters human flaws) over an eighteen-month period.

But in truth, this book was built on thousands of one-on-one and group interviews I participated in with Jeter and his Yankees as a newspaper and Internet columnist who has covered the shortstop since his rookie year.

What was I searching for? The tangible explanation for Jeters intangible grace. The passion behind his pinstripes. The fire beneath his ice.

In many ways, this book was born in my sons closet, filled with frayed and faded jerseys graced by the number 2. I wanted to explore why Jeter became as popular and iconic in his time as Mantle, DiMaggio, Ruth, and Gehrig were in theirs.

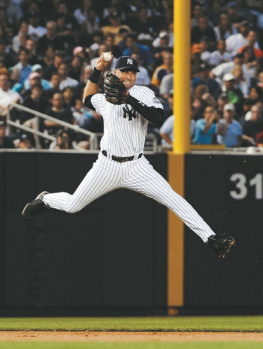

Jeter sure did not hit Ruthian homers, and he did not glide to the batted ball with DiMaggios elegant style. Joe D. could have played the game in a tuxedo and top hat, but not Jeter. The shortstop had to work at it.

Yet Jeter survived an age of steroid-fueled frauds who dominated with their artificial moon shots, and of sabermetric snipers who used their forensics to shoot holes through his standing in the game.

Next page