I cant tell you how much I admire Derek Jeter, everything about him. Hes a symbol of everything thats right about the game, as far as Im concerned. Hes a great role model for other players. When I tell my kids or grandkids about the great players from my time, Ill be proud to say I was on the same field with Derek Jeter.

HOWIE KENDRICK of the Los Angeles Angels, Sept. 11, 2009

CONTENTS

Introduction

by Tyler Kepner

Ch. 1

The Rookie

Ch. 2

The Athlete

Ch. 3

Seasons

Ch. 4

Postseasons

Ch. 5

Off the Field

Ch. 6

The Team

Ch. 7

Character of a Leader

Ch. 8

Legend

INTRODUCTION

DEREK

JETER

by Tyler Kepner

Derek Jeter grew up in Kalamazoo, Mich., next to a baseball field. Every day, just behind his backyard, it was there, calling him to play. And so he did, and he has never stopped.

Jeter wrote a book once, with the former New York Times baseball writer Jack Curry, called The Life You Imagine. The title was perfect, especially if you signifies every child who has picked up a baseball and dreamed. To be sure, there are things we do not know about Jeters life, details he guards closely. But he has lived nearly all of his adult years as a baseball celebrity in New York, and what we know still reads like a fairy tale, the kind we want to believe is still possible in sports.

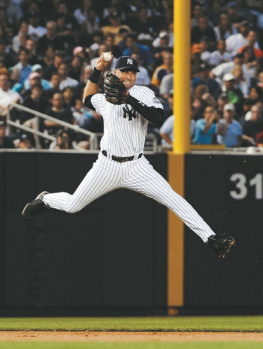

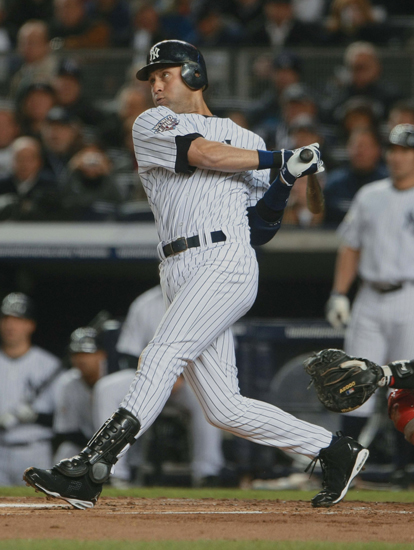

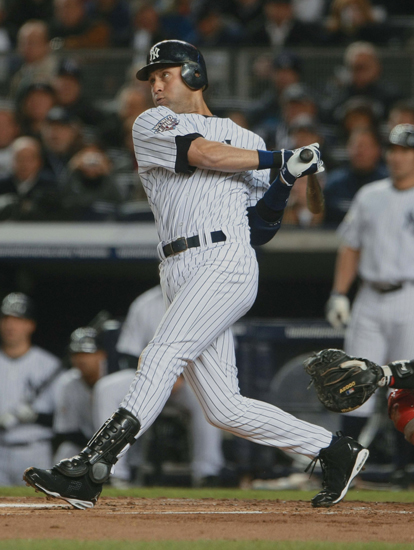

Derek Jeter scores the third Yankees run of the seventh inning in Game 2 of the American League Division Series against the Minnesota Twins, Oct. 2, 2003.

Photo: Barton Silverman, The New York Times

H e was raised in a loving home by an African-American father and a white mother. He was born in New Jersey and rooted for the Yankees, because that was his grandmothers team. He was the best high school player in the country as a senior, and the Yankees drafting high in 1992 because they had finished so poorly the year before selected and signed him.

Skinny and raw, alone in the minor leagues, he made errors prodigiously and cried to his parents over the telephone at night. But he forged deep friendships, with Jorge Posada and Mariano Rivera and Andy Pettitte, and moved to Tampa, Fla., so he could be close to the Yankees minor league complex and training site.

Before his 21st birthday, he was playing shortstop at Yankee Stadium. The next year, he won the World Series, the first title for his boyhood team since he was four years old. He won the Rookie of the Year award and started a foundation that has raised millions to keep children off drugs.

In an age when players routinely change teams, he stayed with the Yankees and became their captain. He won the most championships and dated the prettiest starlets and, eventually, compiled more hits for the Yankees than any player who ever lived. The previous record belonged to another Yankees captain, Lou Gehrig, an iconic name in American history.

By the time he passed Gehrig, Jeter had become the face of the most decorated franchise in sports, with unmistakable appeal across gender and racial lines. Even Red Sox fans respected him. Before the first game of the 2009 World Series, he looked regal and respectful as he escorted the first lady, Michelle Obama, to the field for the ceremonial first pitch. The next night, he looked carefree and hip, bopping his head in the dugout as Jay-Z and Alicia Keys performed on a stage in the outfield.

The song was Empire State of Mind, an anthem to New York City, and Jeter adopted it as his own, asking that it be played before some of his at-bats at the new Yankee Stadium, the $1.5 billion castle his excellence helped build. When Jeter played his first game at the old Stadium, on June 2, 1995, there were 16,959 people in the stands. By 2008, when the building closed, the Yankees averaged more than 53,000 per game.

Jeter did not do it alone, not at all. He came along at precisely the right time in precisely the right era, when the Yankees hard-driving owner, George Steinbrenner, was banned from baseball for paying a gambler to find damaging information on Dave Winfield, Jeters childhood hero. With Steinbrenners influence dulled, the Yankees developed and retained the core of young players who would form the foundation of the teams return to glory. Wise trades and signings, supported by Steinbrenners financial muscle, filled out the rest.

Along the way, the Yankees went global, expanding their footprint by taking the team to Japan and sending scouts and executives to China. They beamed their product to the masses on their own cable network, and their overflowing revenue streams included the new Stadium and reflected an annual budget that defiantly exceeds the collectively bargained limit for tax-free team payrolls.

Jeter, who wants to own a team someday, would have it no other way. He was part of the last generation of Yankees to know the feisty Steinbrenner, before the owners health deteriorated in the first decade of the new century. At one point, Jeter took a tabloid broadside from Steinbrenner, who chastised him for supposedly partying too much. With typical good humor and keen financial sense Jeter and Steinbrenner ended up spoofing their dispute in a commercial for Visa.

Steinbrenner, who died in July 2010, was famous for motivational exhortations, some of them corny and laughable to the modern player. Many sayings are splashed on large white signs in the tunnels leading to the home clubhouse in spring training, including one that has just one word: Accountability. Jeter may not be inspired by those signs, but he lives that trait.

For years, when Manager Joe Torre was asked about Jeter, he would cite Jeters rookie season, in 1996. Although Torre had named him the starting shortstop before spring training, Jeter refused to say the job was his, only that he had an opportunity to win it. It was more than a semantic distinction; to Torre, it was a sign of maturity. The kid knew not to take things for granted. He had a magnetism that made veterans want to follow his example, and his age was irrelevant. Only 21, Jeter was a grown-up.

When he made an error, it was not Jeters way to berate himself on the field or grouse in the dugout. When the Yankees came off the field, Jeter would simply take a seat beside Torre, a silent acknowledgment that he had messed up and would accept the ramifications. Torre would smile and wave him off.

It was a tenet of Jeters credo: a ballplayer should admit a physical error, but not apologize. Mistakes happen, as Jeter knew all too acutely. In 1993, his first full professional season, he made 56 errors for Class A Greensboro. After intensive off-season practice, he was hailed by Baseball America as the games best prospect a year later.

Next page