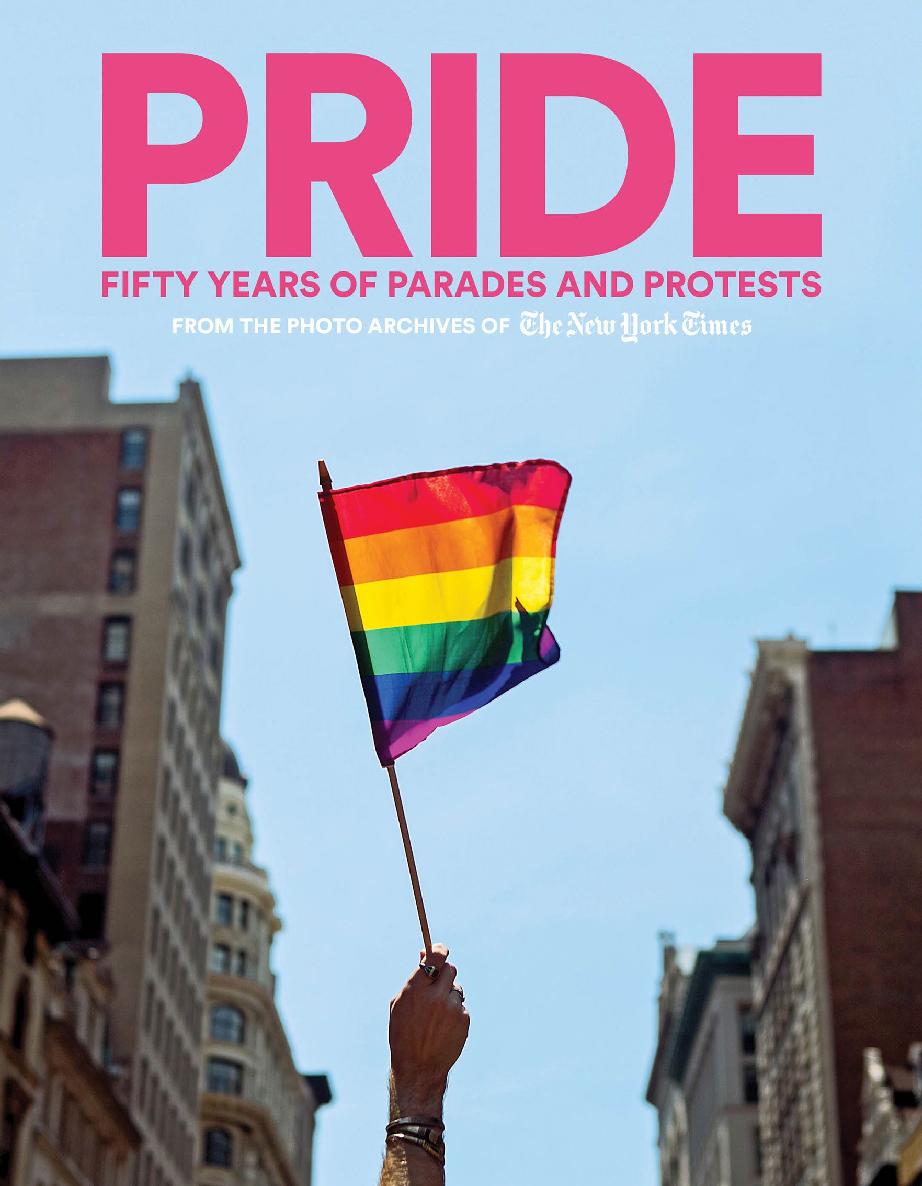

The Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in New

York City is just another barjust another gay

barwith the

thump-thump-thump

of dance music,

and people, men mostly, clustered around the bar,

glancing at their phones, checking out the crowd,

or trying to get a bartenders attention. Some are

dancing and others are slipping out to the street

for a smoke, no matter how cold it is.

But this bar in Greenwich Village has been more

than that for half a centuryit is a shrine. Walk

by any day or night, particularly on Pride week-

end in June, and the sidewalk is clumped with

people posing for photographs next to the neon

Stonewall Inn sign in the window, or in front of

its New York State historical landmark plaque.

Madonna showed up there one New Years Eve.

It has become the symbol of the modern gay rights

movement because of something that happened

there fifty years ago in June.

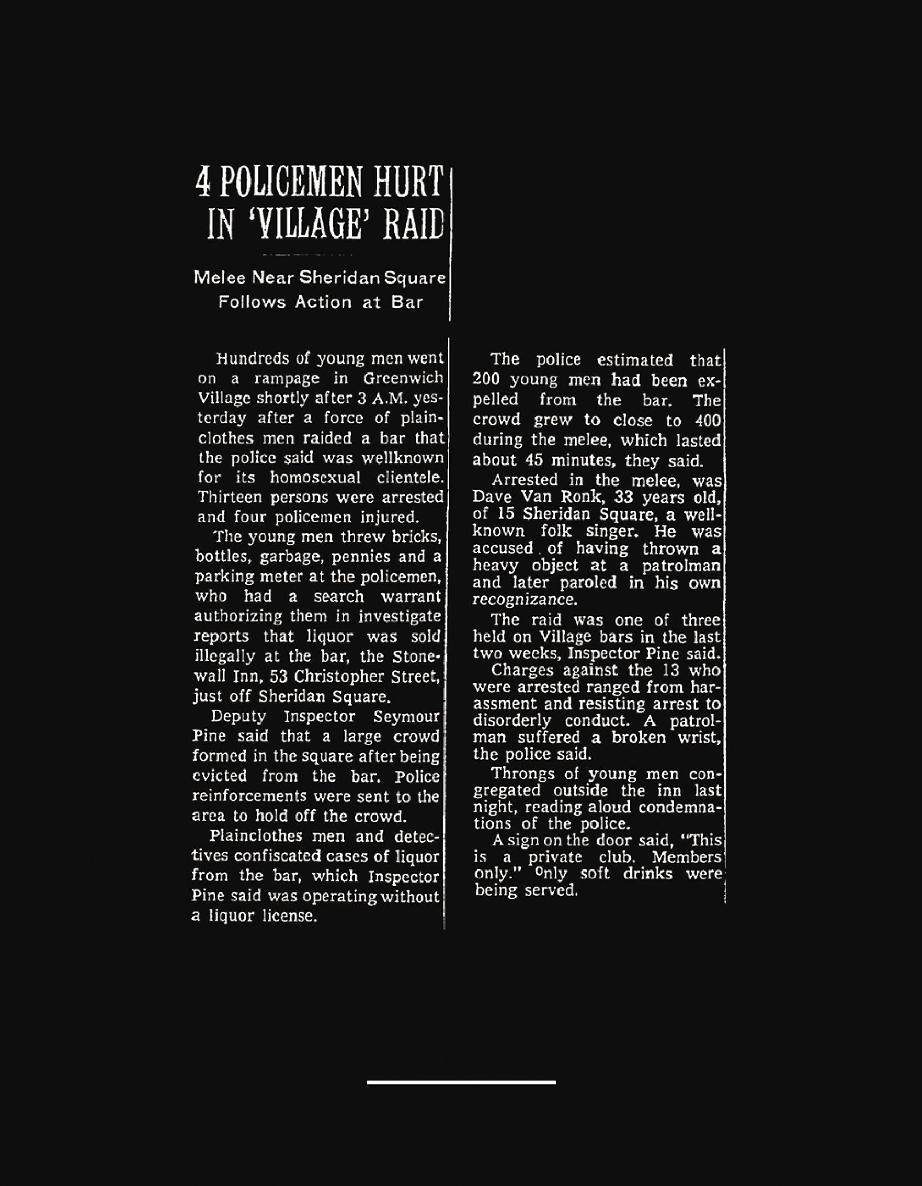

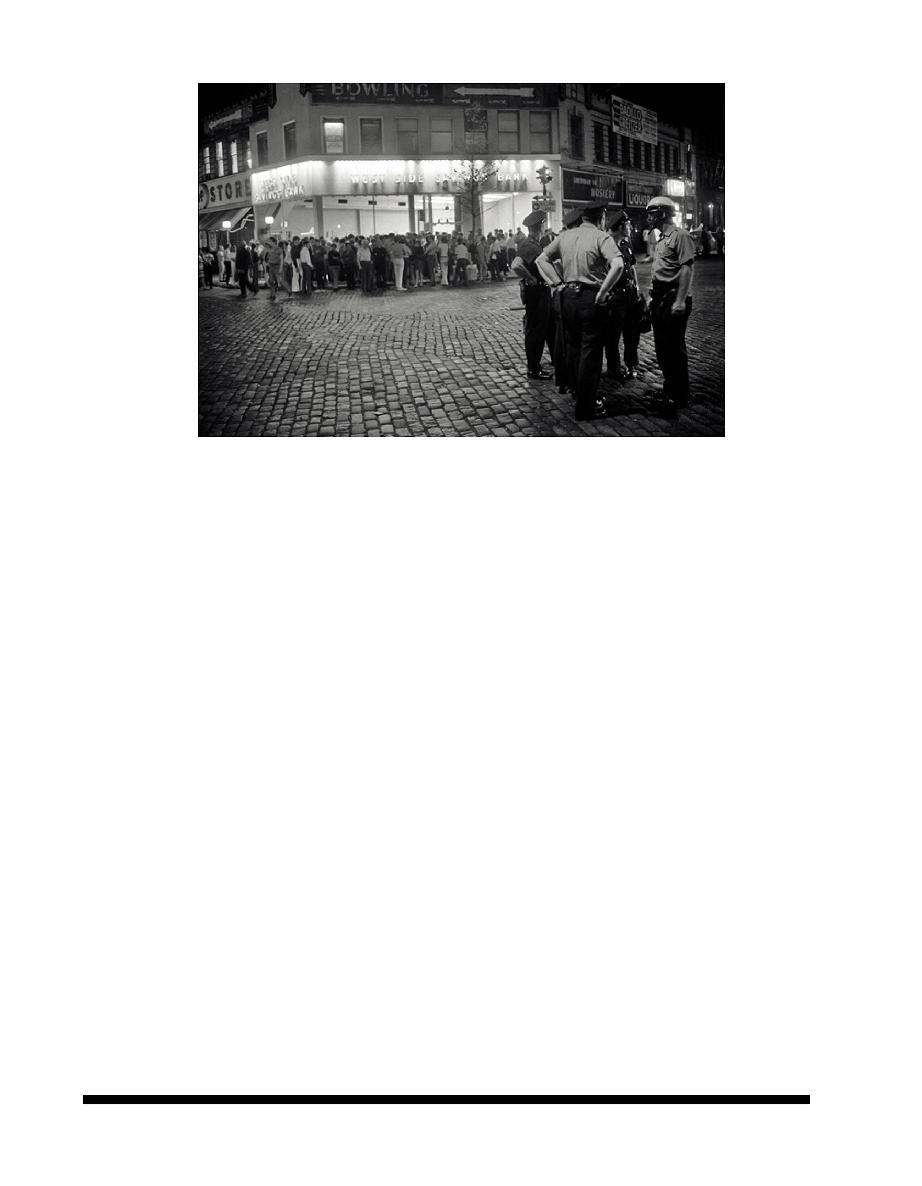

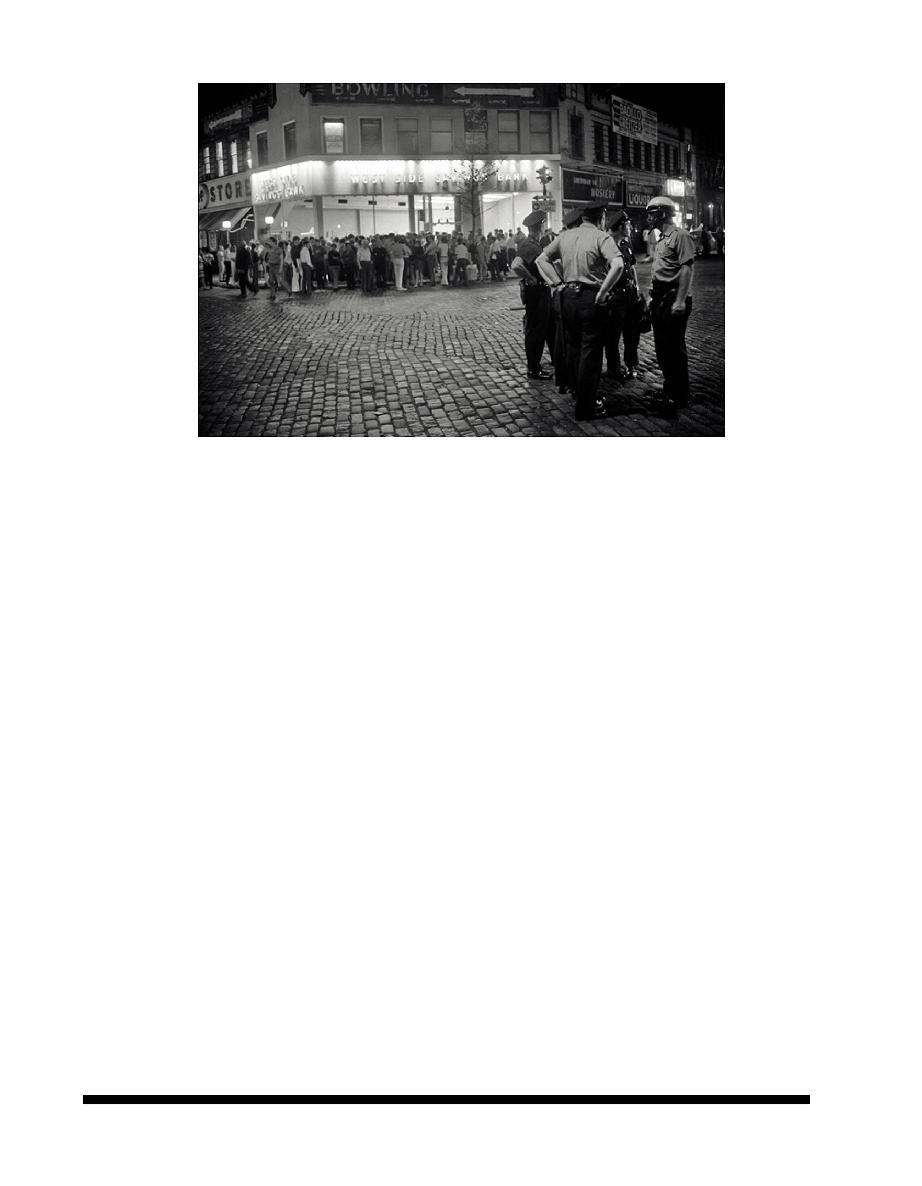

The Stonewall of that era was far different than

it is today. It was a dive, with overpriced, watered-

down drinks and ties to the mob, and a target for

busts and shakedowns by the police. What hap-

pened on the night of June 28, 1969, has been

mythologized and, yes, exaggerated over the years.

In the late 1990s I cowrote a book on the movement

with Dudley Clendinen, and it seemed like every

New York gay and lesbian old-timer we spoke to

claimed to have been there that night. But the fact

is that the police did raid the place, and patrons,

including the drag queens who were an integral part

of the Stonewall clientele, fought back.

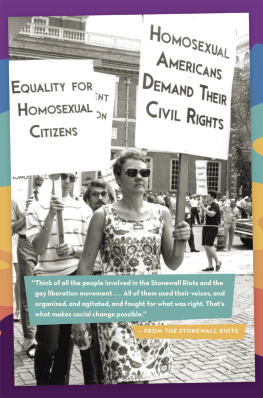

Within days, a group of activistsmany already

beginning to be radicalized by the churn of the

late 1960s: the antiVietnam War demonstrations,

the civil rights struggle, and the feminist move-

mentgathered in a loft to form the Gay Liber-

ation Front. And yes, a movement was bornor

at least a neat moment presented itself to define

the next chapter of a civil rights struggle that had

been lumbering along, mostly out of sight, in the

form of organizations like the Daughters of Bilitis

and the Mattachine Society. Within the next two

years, pride marches were drawing thousands of

attendeesand onlookers, including newspaper

reporters and television crewsfrom Manhattan

to Los Angeles. Those marches continue to this day.

Standing in front of the Stonewall Inn now, its

almost impossible to comprehend the sweep of

change, progress, and tragedy of the past fifty

years. Weve lived to see a revolution in our own

time, Arthur Evans, who sprang to activism after

the uprising, helping to create New Yorks Gay

Activists Alliance, told me in his kitchen in San Fran-

cisco several years ago. If things had been this way

in 1969, I never would have become a noisy street

activist. Instead, I would be a quiet professor leading

an unobtrusive life in a small university.

And what a revolution it has been. The notion

that the United States Supreme Court might one

day affirm the constitutional right of same-sex mar

-

riage would have seemed unthinkable to those early

pioneers, if they had thought about it at all; most

did not. Gay people have moved from the shadows

to positions of stature and influence across Amer-

ican life: television hosts and Hollywood movie

stars; news anchors and city council presidents;

governors and corporate executives.

When Jerry Brown, the former governor of Cali-

fornia, appeared before a gay audience in Wash-

ington, D.C., when he ran for president in 1979

with reporters and camera crews gathered in the

backit was a moment in history. Now, it is hard to

imagine a Democratic candidate for president win-

ning the party nomination without a total embrace

of gay rights. That may not yet be the case for most

Republicans, but even a casual perusal of polling

dataon the views of same-sex marriage and gay

rights among younger Americansleaves little

doubt that Republican candidates will move to the

Introduction

BY ADAM NAGOURNEY

same ground soon enough, if only in the interest of

political survival. The AIDS epidemicfor all the

unthinkable destruction, death, and heartbreak it

spread across the nationproduced a movement

that was more sophisticated in the ways of gov-

ernment, medicine, and public advocacy. Recall

the era-defining manifesto of ACT UP, the AIDS

organization: Silence = Death. Before Stonewall,

many of the older activists were chided for being

too polite and passive. Now the AIDS movement,

and the gay rights movement, had become loud,

demanding, insistent, and very public.

From the beginning, this has been a movement of

fits and starts, of triumphs and disappointments. And

to pronounce the gay rights movement a success

a battle won and donewould be a vast over-

statement, as the election of 2016 made clear. The

advances have taken place mostly in urban areas

and on the coasts; pockets of anti-gay sentiments

exist in many corners of the country. Two women