Getty Images

AP Images

Contents

Foreword by Ron Guidry

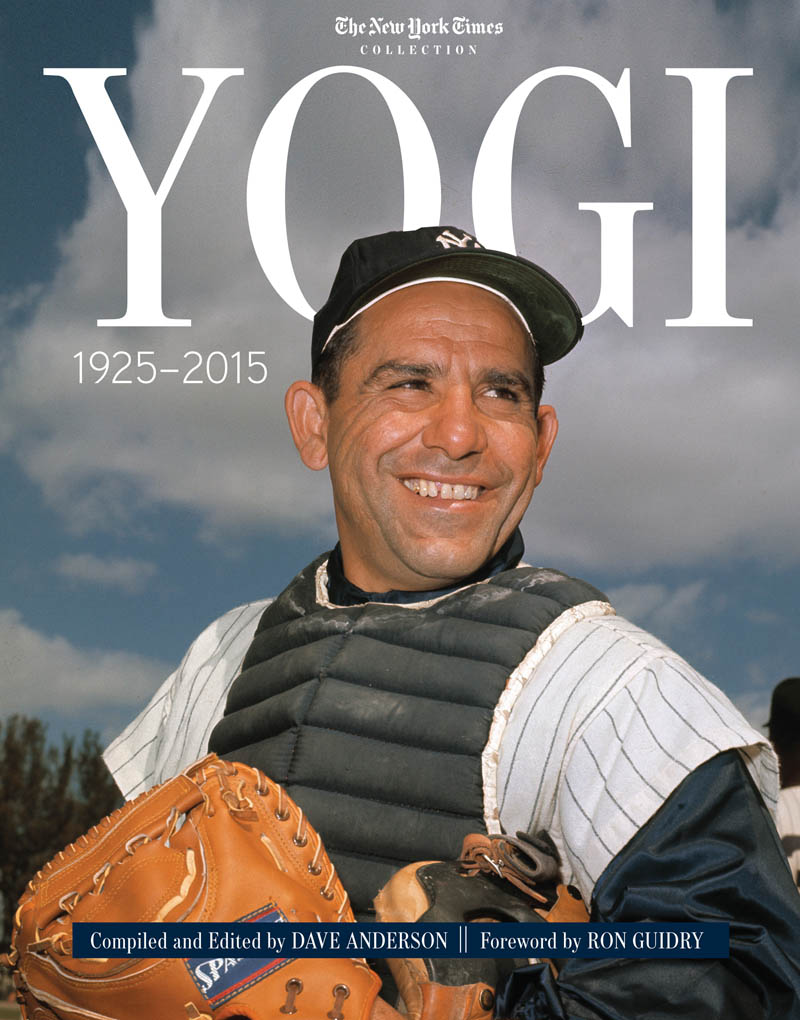

Yogi Berra was my manager, my coach, my Yankees generational elder, and for an unforgettable decade and a half, my spring training companion. He became my dearest friend and was also during that period baseballs greatest ambassador, a fixture and legend, synonymous with the game.

Even if you didnt know much about baseball, you knew about Yogi Berra. His name created an instant recognition not only for older fans who could recall his long-ago career as a Hall of Fame catcher, but also for younger fans, who knew him as one of the games great legends and characters. And for those who had the great fortune of knowing or even just meeting him, it was obvious what made him such an icon.

Some of his lasting fame no doubt was Lawrence Peter Berras colorful nickname, given to him as a youth growing up on playing fields in his St. Louis neighborhood known as The Hill. Part of it had to do with his long association with the Yankees, baseballs most successful and identifiable franchise. But most of it had to do with the essence of the man, with what he stood for and how he represented the game. With honor, with class, and with the unshakable belief that no matter how famous he was, he was no better than anyone else.

He was a typical guy, an everyman from his modest beginnings to his average size and plainspoken ways and for how he treated people in his daily life.

It didnt matter to Yogi if you were rich and powerful like George Steinbrenner or the guy behind the counter where he bought his newspapers. If you were someone he could count on, a person who enjoyed a good chat, he would have time for you. He would listen to what you had to say about sportsand he loved all sportsand especially about baseball and the Yankees, the team he felt spiritually tied to even when he separated himself from the organization for 14 years after Steinbrenners 1985 dismissal of him as manager through an intermediary.

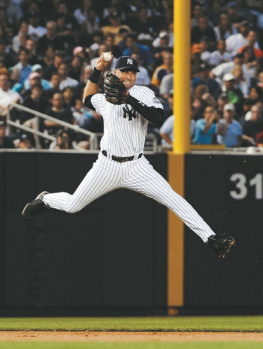

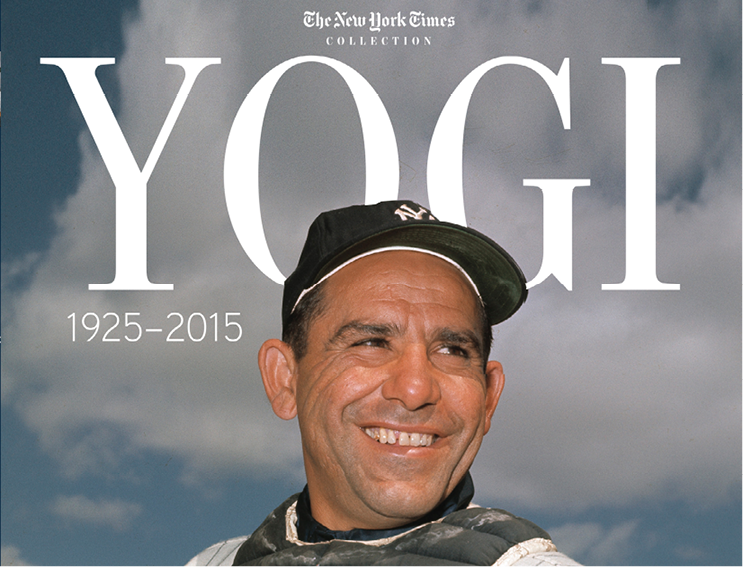

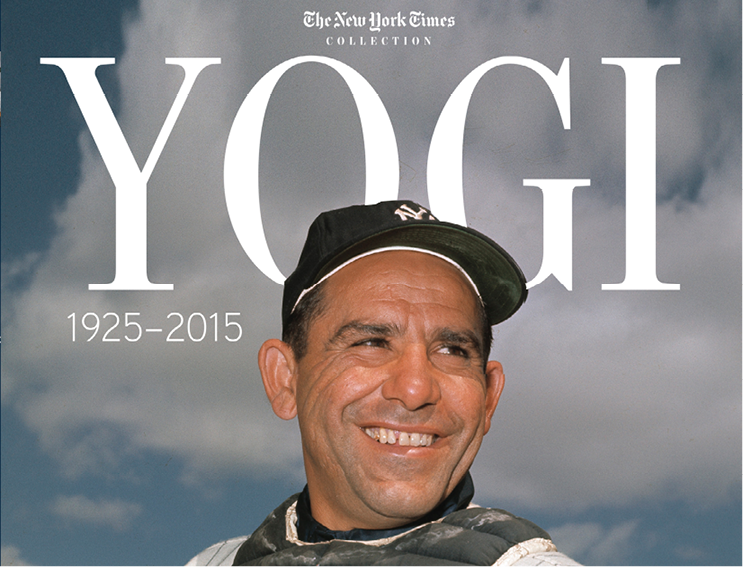

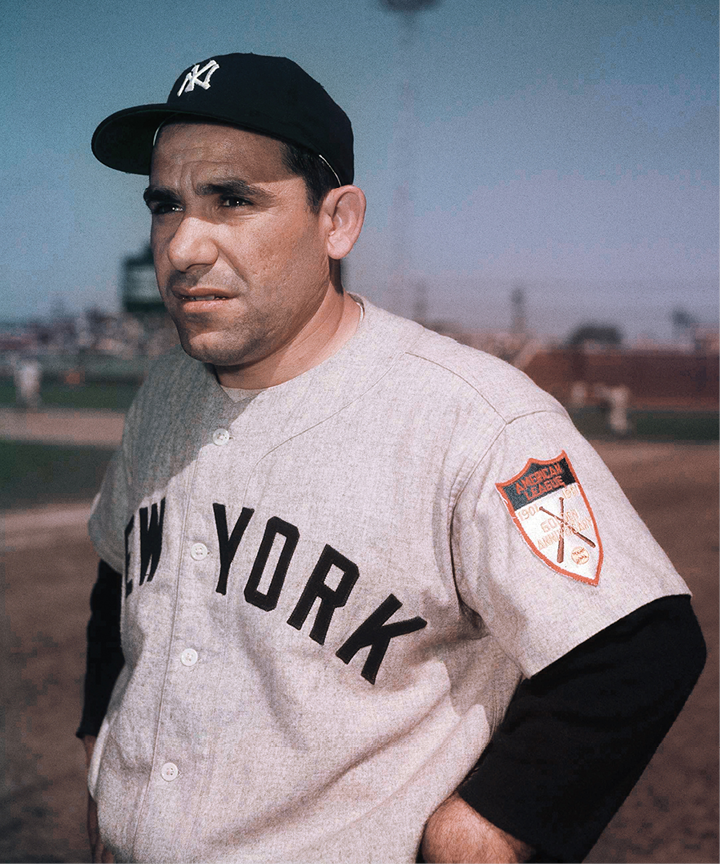

Yogi Berra and Ron Guidry watch together as the All-Star Game logo is unveiled at Yankee Stadium on Tuesday, July 31, 2007. (AP Images)

As Yogis self-exile dragged on, family members begged him to return to Yankee Stadium, but he refused. You might say he was stubborn but you also had to admit he was principled, a man of his word. That made him more of a hero for anyone who had ever been treated with disrespect in the workplace.

When the Boss finally appeared at Yogis museum in New Jersey in January 1999 to apologize, Yogi demonstrated that he was a man of compassion and grace. He not only forgave Steinbrenner but actually became one of his most devoted defenders.

The reconciliation was great for Yogi because he was again able to go back to the clubhouse, schmooze with guys he admired, like Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera, and go upstairs to watch a game. It was great for Steinbrenner because having Yogi Berra around your team was always a blessing. How else to explain David Cones perfect game on July 18, 1999, during Yogis first season back at Yankee Stadium, on the day he was honored and with his 1956 World Series perfect game battery mate, Don Larsen, in the house?

Our spring training relationship began simply enough; he needed a ride from the airport when he came in 2000 to join those of us who worked as on-field instructors. I volunteered and immediately could tell that Yogi was a little out of sorts. He hadnt been to spring training since the teams base had moved to Tampa from Fort Lauderdale. I asked him to have supper with me that night and again the next night. Before long, it was established that he and I would be together during his spring training staysat dinner, the golf course, shooting the breeze in the coaches room. Yogi was a man of unbreakable routines. I was the lucky beneficiary, the chosen partner with access to his encyclopedic knowledge of baseball history.

But better yet was the opportunity to see how beloved the man really was, how badly people wanted to reach out and touch him, asking for an autograph, a handshake, or smile. It hurt Yogi to be off limits or to say no to anyone but it also got to the point where I had to lay some ground rulesotherwise we would never have gotten through dinner.

As he got older, and needed more help in getting around, I took on more responsibility in caring for Yogi, to help keep him safe. People who read about our relationship in The New York Times and in a subsequent book would tell mesome with tears in their eyeshow it reminded them of a relationship theyd had with an aging relative. I would tell them it was never a case of charity, or even kindness, as much as it was a privilege to spend that time when you love and respect someone as much as I did Yogi.

I think I can speak for the sport and its fans when I say that I relished every minute.

Introduction by Dave Anderson

The 8 Lives of Number 8

As a Yankee rookie in 1947, Lawrence Peter (Yogi) Berra was issued uniform number 35, but the next season, in the absence of coach Bill Dickey who had worn number 8 as a Hall of Fame catcher, 8 was stitched on the back of Yogis pinstripes and road grays. For decades Yogi wore 8 as a Yankee slugger, catcher, outfielder, manager, coach, and Old-Timers Day fixture. In a 1972 ceremony, the Yankees retired his 8 (along with Dickeys 8) and no other Yankee will ever wear that number.

As if anyone could. Or would dare.

Number 8 wouldnt look right on any other Yankee except Yogi, who was sturdy and short at 5 feet, 8 inches and 191 pounds in his prime. But in retrospect now, his number 8 represents his eight lives in baseball:

1. As a teenager on the sandlots of The Hill neighborhood in St. Louis, Berra was signed by the Yankees after his hometown Cardinals ignored him. Following the 1943 season with the Norfolk (Virginia) Tars in the Class B Piedmont League, where he hit .253 with seven home runs, he enlisted in the Navy during World War II. On D-Day, he was a 19-year-old seaman first-class on a 36-foot L.C.S.S. rocket boat off Normandy. The S.S. stood for Support Small, he recalled half a century later, but to us the S.S. was Suicide Squad. We went in before the army. We fired our rockets, a 5-inch shell. Then the army hit the beach. When the shooting started, it looked like Fourth of July fireworks. I can still hear Ensign Holmes yelling, Get your head in. He later served off the coasts of Italy, France, and Africa before returning to the New London, Connecticut, base. I told em I didnt volunteer for submarine duty, he said, remembering his New London posting with a laugh. But they wanted me to play baseball there.

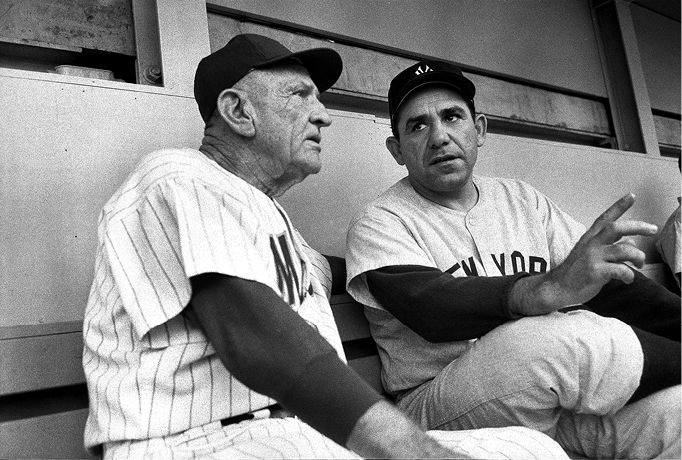

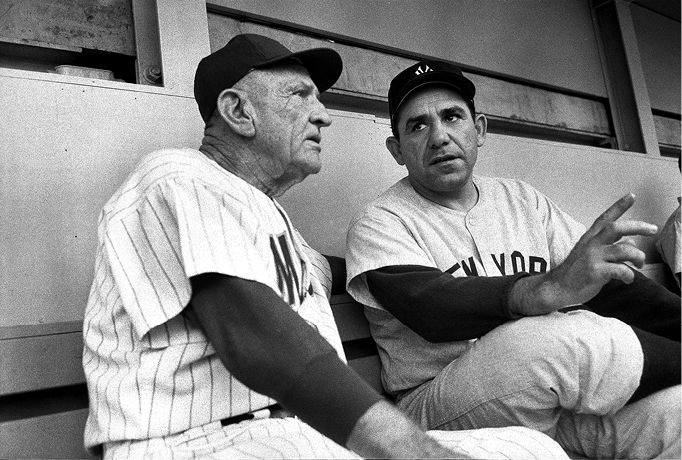

Casey Stengel, then manager of the Mets, and Yogi Berra, then manager of the Yankees, talk at Shea Stadium in 1964. (Larry C. Morris/The New York Times)