Jacket copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

FIRST THINGS FIRST. Why did I write this book? The short answer is that I love my dad. That may sound obvious, but it is part of a larger answer: my dads love for me did nothing less than save my life.

When he died in 2015 at a very well-lived ninety years of age, everyone knew Yogi Berra as an American icon, a legend of almost mythical proportions. Far fewer know me as the son who made it to the big leagues, following in his footsteps. I made it through ten years. I was on a world championship team, the 79 We Are Family Pittsburgh Pirates. I even set a recordnot anything like my dads stockpile of them but a record nonethelessreaching first base seven times on catchers interference. Hey, any way you can get on base, right? Im sure Dad would have said just that. I once led baseball in hits by an eighth-place hitter in the lineup. I also played for my dad when he managedfor sixteen gamesthe 85 Yankees, the biggest thrill of my life, making me the first son to play for his father since Earle Mack on Connie Macks Philadelphia Athletics in 1937. Thats my piece of history.

I wasnt a great player, certainly not in the same universe as Dad. People in the stands would sometimes yell at me, Youll never be as good as your old man! But I always thought, who was? And I was fine with that.

I wasnt a bad. I played third base and shortstop. Like Dad, I had a good glove. The bat? Not as much. I hit .238, had forty-nine home runs, 278 RBIs. I had more hits than any son of a Hall of Famer, 853, fifty-four more than Dick Sisler, son of George, and when I retired my dad and I had hit the most home runs by a father and son, 407 (since surpassed by the Fielders, Griffeys, and Bondses). Sure, I had only forty-nine, so thats like Tommie Aaron being able to say he and his brother hit more home runs than any brothers in historywith Tommie hitting only 742 fewer than Hank. But, hey, dont take that away from us.

The historians, the SABR crowd, rank me on the same level as players like Clete Boyer and Flix Mantilla. Ill take that. The flip side is, I had a chance to be better, much better, a star. When I came to the majors, I was only twenty and the best prospect in the minors. And while I dont make excuses for not being what I could have been, theres no doubt that my downfall was getting involved in the drug plague within the game during the 80s. Cocaine was the villain. It took my career away. Im not alone. Ask Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden. And Steve Howe. The Yankees, for some reason, have had a bunch of em.

Of course, I put more than a baseball career in jeopardy. And at the heart of this story is that it was my father and my family that turned me around. Only by hitting bottom did I learn what my dad had tried to teach me when I was a child growing up in his massive shadow. Those lessons are what I wanted to write about. I only wish I would have appreciated them when they could have saved my career.

I had a box-seat view of my fathers life and death no one outside our family did, an intensely personal view of years that were both wonderful and painful for both of us. Its not every day that someone whos been written about as much as my fatherand he was one of the most written about athletes of all timecan be seen in a new light. But I had that light, and after a great deal of soul-searching, I wanted to share it, because it was good for my soul. They call that a catharsis.

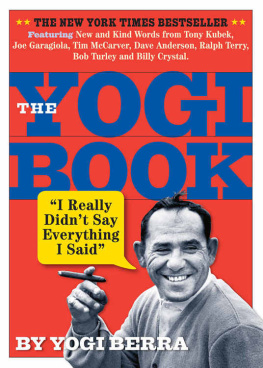

The other works about Dad were perfectly justified. A family friend of ours who helped establish the Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center wrote a couple with Dad. His famous Yogi-ismsthose observational baubles of fractured but solid logicalone have filled more than a few books. People still havent gotten their fill of him, because he was truly one of a kind as an American icon, a national treasure, and the most quoted man in the world. Its automatic that when his name is mentioned, people will reflexively smile. And yet no book has told of the Yogi I knew, the father of three sons, grandfather of eleven, great-grandfather of one. That is the story of us, our family, and its one that only my brothers and I know.

In many ways, Dad and I both had to grow up and learn from each other what life really meant. I hope that when he died, he knew I loved him and had learned from him, that I carried his good name. And I hope I taught him that life has its pitfalls and we all arrive at our destination on different roads but end up on the same ground.

I dont think of this book as another Yogi history, but rather as a letter to him from my heart. That Dad was a legend is incidental to his role as a father needing to set his son straight. I knew that reliving the details of the story would be painful. It was something like therapy revealing a very stupid span of my life that reflected badly on him and wrecked a burgeoning career. Getting my two older brothers, Larry and Tim, and my oldest daughter, Whitney, to pitch in with their observations helped a lot, because their memories filled in gaps and allowed Yogis boys to tell the story from all of our points of view.

I wont say it aint easy being me, because I have been extremely fortunate to have grown up with the family I had and to have walked in the footsteps of my dad all the way into the big leagues. Yet I have to live with the shame and guilt of my descent. Today, three decades after I hung em up, I will walk through an airport or mall and someone will know me, even without the bushy, porn-movie mustache that was my signature as a player but I said goodbye to in the 90s. Maybe its because, as I age, I look more like my dad. Ive been told I look like I could still play. But my nose keeps getting bigger, my ears stick out more, and wheres my hair going? Back in 75 when I was a nineteen-year-old wunderkind, my manager with the Pirates, Chuck Tanner, said I was handsomer than my father. I wish Chuck were still around, so he could say it again.

Its flattering, but only until someone will segue from Hey, didnt you used to be? to You had a drug problem, right?

I can accept that. Because its true. I used cocaine for over a decade. Richard Pryor once said he used Peru. Well, I used it through my promising career with the Pittsburgh Pirates, when I got swept up with ten other big-league players in the bust and trial of a Pittsburgh drug dealer in 85, baseballs second-biggest scandal since the Black Sox threw the 1919 World Series. Youd think that would have set me straight, but I kept using, thinking I had it all under control. Even after I retired and was arrested in a 1989 New Jersey drug investigation, I had rationalizations, telling myself I was doing cocaine the right way, somehow within the rules.