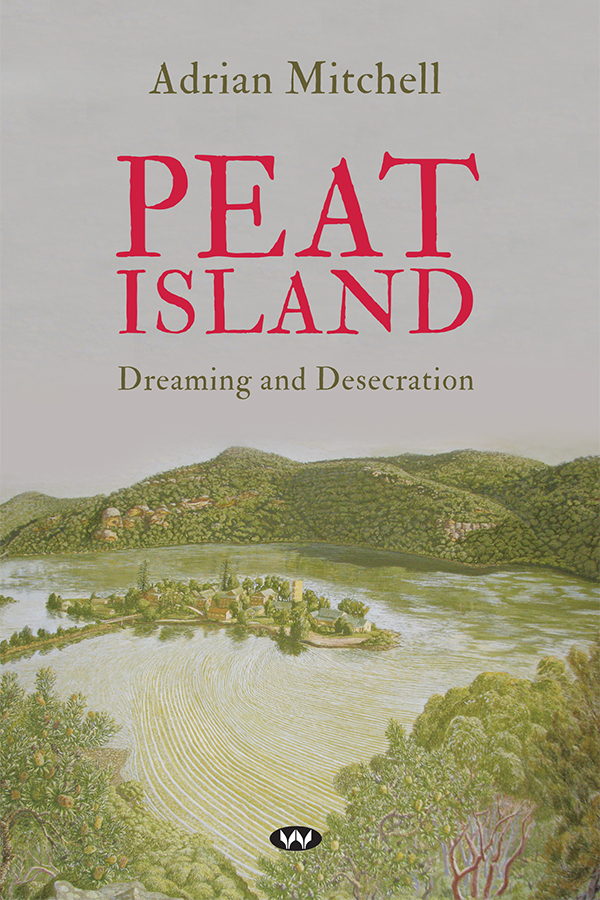

Wakefield Press

PEAT ISLAND

Adrian Mitchell has written a number of books, published by Wakefield Press, with a particularly Australian reference. They recount the stories of people and communities that should be better known than they are. Plein Airs and Graces was short-listed for the Prime Ministers Literary Award.

He taught at the University of Sydney for many years, and has now retired to live on the edge of Ku-ring-gai Chase, close by the imposing Hawkesbury River.

Wakefield Press

16 Rose Street

Mile End

South Australia 5031

wakefieldpress.com.au

First published 2018

This edition published 2018

Copyright Adrian Mitchell, 2018

All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the

purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under

the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission.

Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

Cover designed by Mara Page

Edited by Penelope Curtin

ISBN 978 1 74305 559 5

For Meg and Catherine

Contents

Preface

Peat Island, formerly Rabbit Island, is now again as it once was, empty, latent, dreaming. Long ago it had another name, Kooroowall-Undi, in the lands of the Darkinjung, the acknowledged traditional guardians, past and present, of this spectacular, magnificent country. Whatever this place means, whatever it has meant, and whatever it is to mean, must be learned from them. We have desecrated it, and their country, for far too long.

This project, a record of what evolved there, was undertaken at the suggestion of Peter Davis, who raised the spectre of Peat Island as a challenge: Can you turn that into a book? Perhaps, or perhaps not. The verdict on that awaits the judgement of the reader.

Possibly it should not have been attempted, because the topic is acutely painful, and distressing. But then, its complicated story ought to be told. The weird hold that Peat Island has had on the public imagination for more than a century is precisely because no one really knew what was happening there. It has been a secretive place, exclusive, sinister, or so the public was led to believe from occasional lurid reports in the press, of escapes and drownings and unspeakable events. Inside its perimeter lurked some kind of darkness. The unknown, the unreachable.

Inside its perimeter were unfortunate souls, some of whom suffered dreadfully, either from their congenital condition or at the hands of cruel attendants. Such callousness was perpetrated by an abnormal minority, as in other institutions too. The great majority of the nursing staff, however, were caring decent people, doing a difficult job in difficult conditions; and through them many residents came to love the island. It was, after all, their home. They were saddened at the end to be removed from it by departmental decree. Evicted, in fact; literally unsettled.

The complexion of the hospital changed enormously when the mentally ill were separated from the mentally disabled and transferred to other placesa separation echoed at the administrative level, with the division of responsibility between the Department of Health and the Department of Community Services (and thence, Disability Services). But by that time the belief that it was a frightening place, a no-go zone, had become deeply entrenched. And perception, as is commonly the case, became the reality.

Throughout, Peat Island was largely left to itself, more stranded than isolated.

The record shows that it was overseen by an imperfect system, just as it shows that the care provided to and for mental health patients in New South Wales has been a very celebration of imperfection, both legislatively and administratively. Across its history, Peat Island Hospital in its various incarnations was, like other comparable institutions, not well enough funded. It was for a large part of its history overcrowded, for much of the time it was understaffed, or the staff were not properly trained, and it struggled to cope with what must have seemed neglect. Certainly that is what it came to look like.

The institution was never right. It was a botched job right from the beginningit was never purpose-built.

The residents themselves, though, were in their own way thoroughly engaging. And the emphasis in that statement has to be on the phrase in their own way. Once when my wife was visiting a programme for the intellectually disabled, one of the girls there asked her if she would like a cup of coffee. Thats very kind of you, she said. Actually, what I would really like right now is a glass of water. Nearly fifteen minutes later the girl came back, with a cup of coffee. I changed my mind, she said.

You cant afford to be inflexible around the disabled. And you certainly cant afford to take them for granted.

When in 2010 the Peat Island Centre was finally closed down, Laila Ellmoos was commissioned by the Department of Ageing, Disability and Home Care to write its history. The result was Our Island Home: A history of Peat Island, and her book has served as an authoritative reference for various government publications since. In writing this book I have followed her lead when it suited, just as on occasion I have taken off on my own. That is the nature of tracks through the wilderness. You find your own way.

There is always help when you know where to look. I have benefited from the local studies collections at Hornsby and Gosford libraries, and made good use of their resources; likewise, of the holdings of the State Library of New South Wales and the Fisher Library, University of Sydney.

I thank John Andrews, secretary of the Mooney Cheero Point Progress Association, for helpful information and advice, as well as for showing me around the island. Juno Gemes assisted with useful insights at the beginning of this project. Greg Willmette and Bruce Breese of the Mooney Mooney Club gave almost instant replies to questions of detail.

My gratitude goes to Graham Quint and Leica Wigzell for providing a copy of the National Trust Register listing report on the Peat Island landscape conservation area, approved in March 2017. Thanks to Bob Baker, for the story of his too-close encounter with the residents. To the team at Wakefield for another handsome book; and to Penelope Curtin who scrutinised the text with her customary exactitude.

Special thanks to my good friend and former colleague, Geraldine Barnes, for prising open resistant electronic shutters and finding ways into mines of information; and then for reading the first drafts of what emerged from that treasure trove.

Finally, as always, to Maureen, for reviving cups of tea, and customary sage counsel; and for her bravery in traipsing through bush tick country. The place of bandicoots, after all.

Adrian Mitchell

Sydney, 2018

Timeline

| 1831 | George Peat granted an allotment at Fairview (Mooney Mooney) Point |

| 1834 | Mud Island (Milson) named on Major Mitchells map. |

| c. 1840 | |