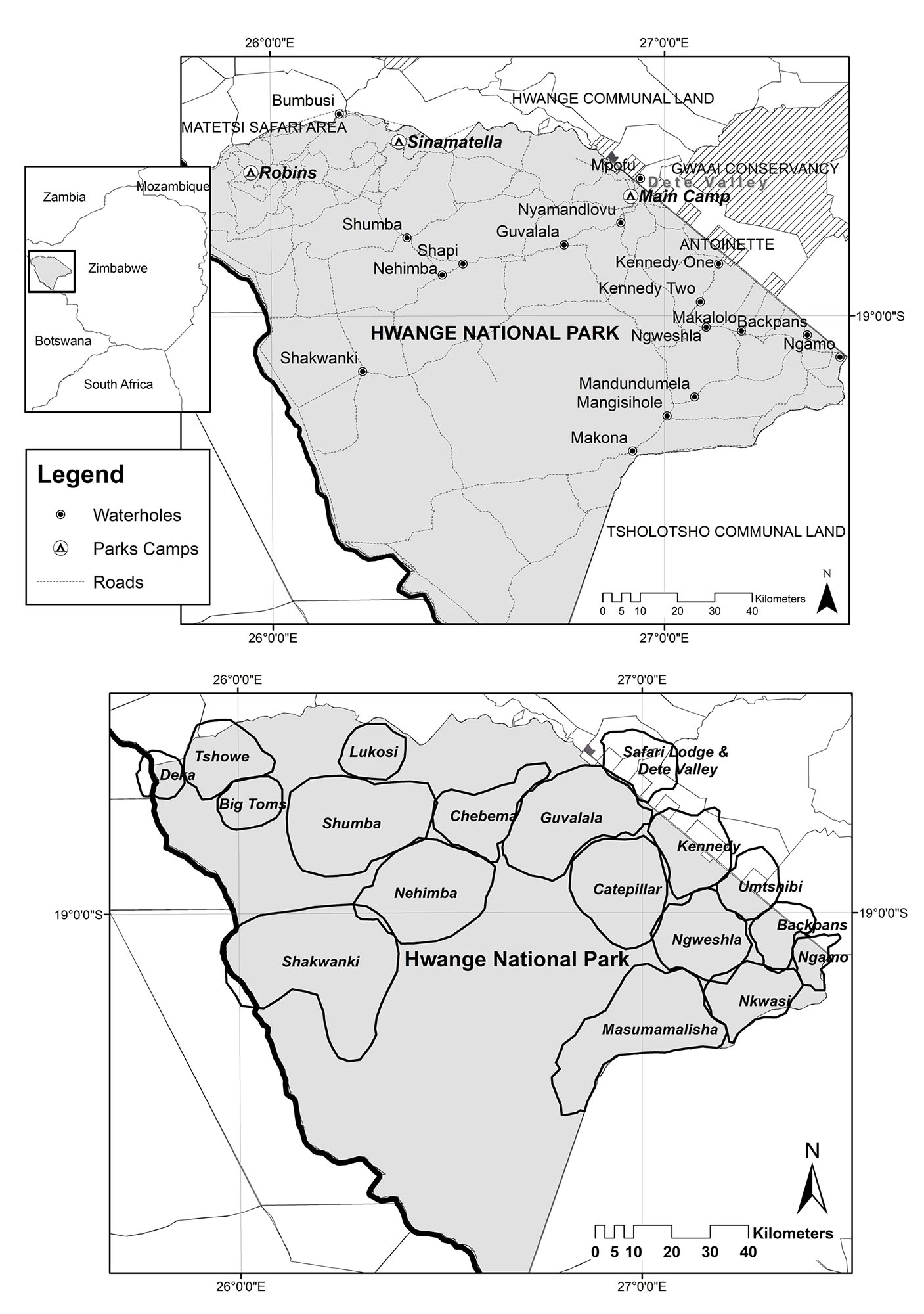

Locations of the main lion prides studied in Hwange National Park.

Cecil charging the research vehicle seconds after he was first darted.

A stones throw away, the reclining male lion moved restlessly as I edged the four-wheel-drive Land Cruiser forward across the uneven ground. My wife, Joanne, and I had been slowly maneuvering closer to him for the last half hour, stopping the vehicle whenever he became uneasy. Our cautious advance was gradually allowing the big cat to become accustomed to our presence. The trucks tires crunched over the dry grass tufts. The pupils of the lions yellowish eyes widened as the potentially threatening vehicle approached. His black-tipped tail twitched a silent warning. Twenty meters away from him, I cut the engine once again and we sat motionless, giving him time to relax, making no movement or noise. As a newcomer to the area, he was not habituated to vehicles or people and could behave aggressively, or worse, run away before we could catch and tag him with a radio collar. Once fitted, the collar, with a radio transmitter and sophisticated global-positioning system, would log his location every hour and allow us to study his ranging movements and behavior.

Joanne held the loaded dart rifle, ready to pass it to me as soon as I saw an opportunity to shoot a tranquilizer dart into the wary lion. To be sure of a clean shot, we needed to be close to the lion and ensure there were no grass stalks that could deflect the light dart. After a few minutes intently scrutinizing the intruding vehicle, the lion relaxed again, shifting position to scan the open plain and the bush under which his brother was mating with one of the pride females. The change in position gave us a chance for a shot. Through the vehicles open window, I slowly raised the rifle to my shoulder, bringing the red dot of its optical scope to bear on the lions muscular, tawny body. A gentle squeeze of the trigger and a phut of compressed air sent the dart punching into the cats shoulder. He jumped in surprise and gave a guttural snarl of annoyance. He glared furiously at the vehicle and, with a throaty warning growl, rushed forward a few meters in a tail-lashing mock charge. Teeth bared, he stopped, attention fixed on us, waiting for a cue to unleash a final assault on the vehicle. We froze. Any careless movement could precipitate a full-on attack. However, with nothing to provide a focus for his anger, his attention wandered. Honor satisfied, he stalked off stiff-legged to a nearby termite mound to nurse his wounded dignity. We sighed as the tension of the last half hour was released, the adrenaline of stalking and darting the lion ebbing from our bodies. With the dart in, we now had to wait for the drugs to take effect on the big cat. After five minutes he started to look groggy. After fifteen minutes his great head slumped onto his enormous paws. It was now safe to approach and handle him.

It was November 8, 2008, and the Lion Research Project had been running in Zimbabwes Hwange National Park for nearly a decade. The project had been studying the population dynamics of lions and had by this point already collared more than 160 of them. This male, though, was uniquedestined to become one of the most recognizable wild animals in the world. That day, in the early morning sunshine, deep in Hwange National Park on the Makalolo plain, dotted with gnarled mitswiri trees, we had no notion of this.

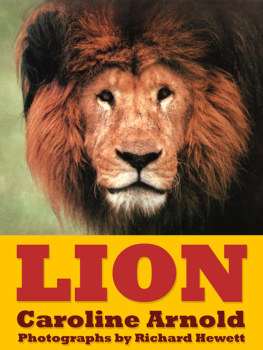

Seeing a lion this close up is an experience that even seasoned wildlife professionals dont often get. Despite having studied these animals for nearly twenty years, I still marvel at their sheer size. A male is close to three meters long from nose to tail tip and stands 1.2 meters at the shoulder. A large male lion tips the scales at around 225 kilograms (495 pounds), the combined weight of two of the largest American football players. A males size is augmented by a thick mane of dense fur on his head, chest, and shouldersa signal of strength and virility that also serves as protection from raking claws in territorial fights with other males. Male lions are designed for war. They are the battle tanks of the cat world. Their adult lives are spent defending their territories and prides of females against other males. Lionesses are about 30 percent smaller, lithe, and muscular but no less formidable. A lioness has evolved as a huntress; her speed and raw strength ripple through every inch of her honey-colored body. When handling an immobilized lion, I often remind myself of the sheer size of these creatures by resting my hand against the underside of the soup platesized paw. A lions paw is pretty much the same size as a mans hand, fingers splayed. Five lethally sharp claws, each three centimeters long, are safely sheathed within the paw. They are used as grappling hooks to pull down prey many times a lions size, or as slicing, cutthroat razors in territorial battles. These animals are beautiful and dangerous and perfectly adapted to fulfill their role as the ultimate predator on the African plains.

Yet, despite their magnificence, they are under real threat. Their numbers have declined precipitously over the last decade. Across West Africa, where lions were historically widespread, there may be as few as 400 remaining. Lions are doing similarly badly across Central Africa, where insecurity and conflict have undermined the safety of their previous strongholds. It is only in eastern and southern Africa that lions are relatively safe. But even there many populations are declining, some of them frighteningly fast.

This is startling given that lions are one of the most recognizable and beloved mammal species in the world. What child in the Western world has not empathized with young Simba, the central character of the Disney animation The Lion King , one of the highest-grossing films of all time? Who has not enjoyed the spectacle of Alex, the Central Park Zoo lion in Madagascar , cavorting incongruously with a hippopotamus, a giraffe, a zebra, and four psychotic penguins? The lions image and reputation for strength and bravery have been appropriated by royalty, capital cities, sports teams, and multinational corporations. Id hazard a guess that there are more images of lions in sculptures, carvings, gargoyles, and coats of arms in central London than there are living lions in the whole of West Africa. Surely, given their obvious cultural resonance, lions cannot be allowed to become yet another species balancing precariously on the brink of extinction? Or, worse, completely disappear. Yet this is what is happening. Lions will not disappear in the next few decades, or perhaps even in our lifetimes, but their slow, inexorable decline is a reality. And aside from a few concerned conservationists, humanity is doing little to prevent it. By the time the world wakes up to the enormity of what we are about to lose, it may already be too late.