From the families of the victims to the tribe of lawyers and investigators who toiled, in some cases for decades, to ensure justice was done.

And this book, which reflects on my home and history, is dedicated to my loved ones. The people who sustain and invigorate me.

To my eternal benefit and joy, my daily touchstone is my wife, Louise. She has always allowed me to pursue dreams, walking with me every step of the way as my most ardent supporter and most helpful critic; my friend, my love, and an amazing mother.

I am also blessed with three amazing children, Courtney, Carson, and Christopher, who have enriched my life beyond words. My granddaughtersCourtney and her husband Rip Andrewss babiesEver and Ollie, are the brightest lights in my sky these days.

My sister, Terrie, and her husband, Scott Savage, have been with me every step of the way in recent years as weve cared for my ailing parents. Gloria and Gordon Jones showed me the importance of decency and hard work and passed on the loving tradition of my maternal grandparents, Ruby and Oliver Wesson, and Dads folks, Charlesie and Edwin Jones.

In Harper Lees American classic To Kill a Mockingbird, the author conjures a modest country lawyer from imagination and memory, from pieces of her own father, and sets him against Southern society itself, against prejudice and meanness and the petrified opinions of a doomed but lingering ideal.

The lawyer is asked, in her fictional story, to save a young black man wrongly accused of a terrible thing, and he takes on that task with full knowledge that it will cost him in that society, in an old South that is willing, if not eager, to believe the worst of a man for little other reason than the color of his skin.

The lawyer, more of an old name than old money, cannot, in the end, save the man. His victories are noble ones, but moral ones. It is one of the best books I have ever read in my life, but as a child of the Deep South, a child of Harper Lees Alabama, I have always been haunted by that book and its lessons. I have never seen much good in a moral victory, at the lip of a grave.

There are just too many ghosts down here, so very many. So many victims gone unavenged. So much justice denied. So many young men, old men now, left free to gloat and preen and even confess, in the company of like-minded men, to their meanness and even murder.

Moral victories, in such a landscape, are a thing of fiction. Harper Lees great book reminded us of that, beautifully but tragically, and became a kind of sermon for our time.

But it was fiction.

Atticus Finch was just a name in a story.

Men did their evil across the decades and got away with it, while good men stood by and did nothing.

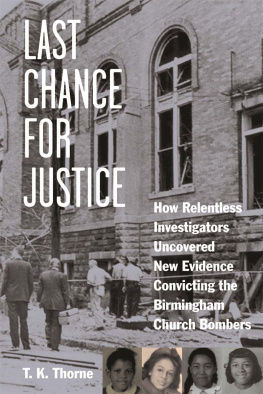

I was four years old when the worst of it happened, the nightmare story of the Jim Crow years. In 1963, children marched for their civil rights in Birmingham, the big city to our west. That fall, elementary and high schools began a court-ordered integration, and the segregationists, seeing their world come to pieces around them, did the unthinkable. They targeted the children themselves.

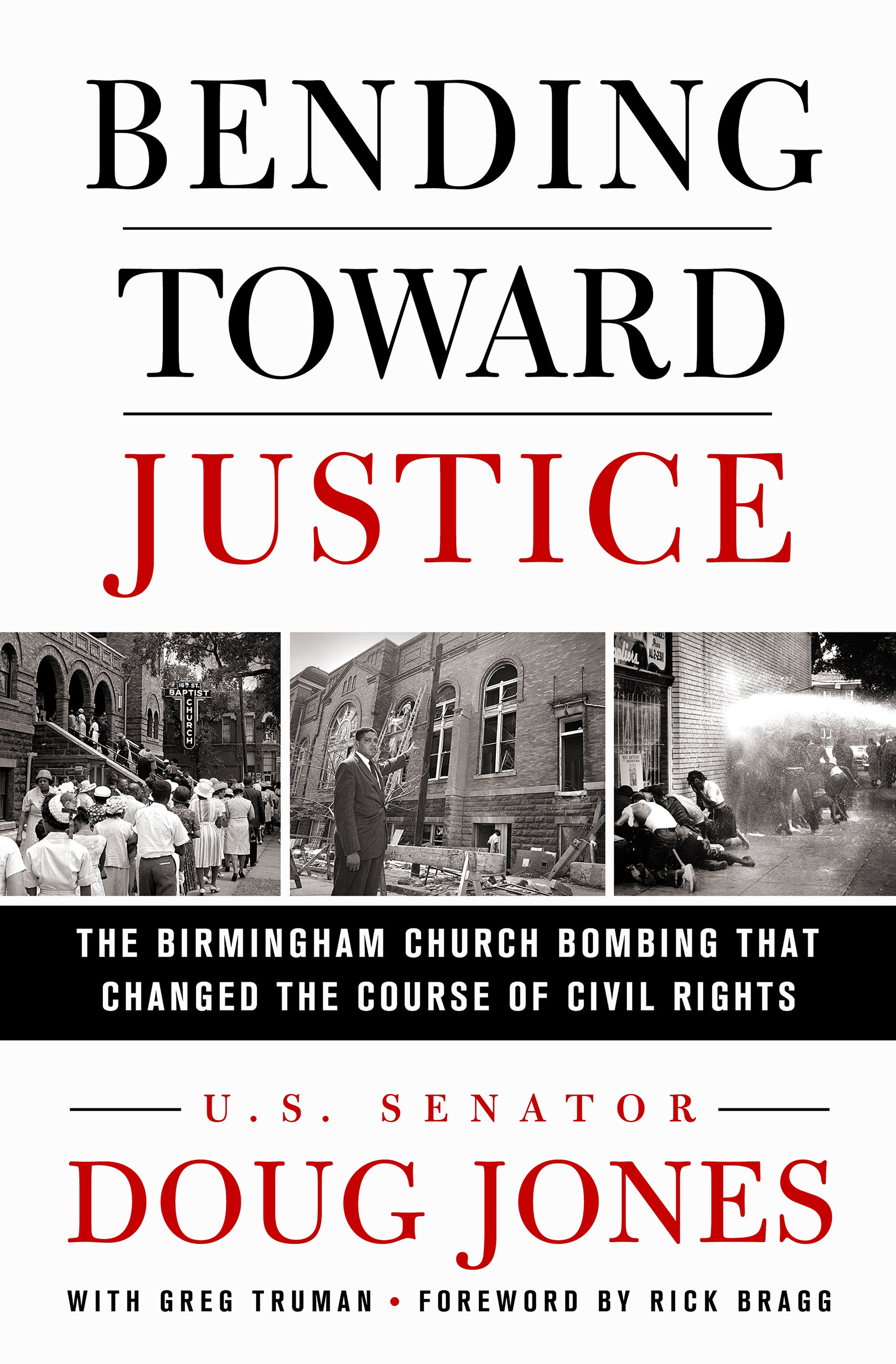

On September 15, 1963, Ku Klux Klansmen planted a powerful bomb at 16th Street Baptist Church, timed to go off just minutes before Sunday services. In the church basement, four little girls were getting ready for the program that day.

Addie Mae Collins.

Cynthia Morris Wesley.

Carole Robertson.

Denise McNair.

The blast took them from this life and burned their names in history, and the bad men, the worst of cowards, got away with it, for years and years. There were attempts at justice, but the courtrooms in those days were merely turnstiles. The accused smirked around their Winston cigarettes. Police pumped their hands.

It was shameful.

Finally, in 1977, Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley worked what some lawyers still consider a courtroom master class and brought to trial and convicted a single defendant, Robert Chambliss, the man his friends affectionately called Dynamite Bob.

It was better than a moral victory. But everyone, from investigators to newspaper reporters to the man and woman on the streets of that city, knew that Dynamite Bob Chambliss did not act alone, knew that somewhere out there, men gathered in the shadows to remember and relive what they had done, and even brag.

In the courtroom that day, as the gavel came down hard on Chambliss, was a young law student who had skipped classes day after day to see it all unfold. He was not some Yankee firebrand. He was a boy from the outskirts of Birmingham, where the smokestacks turned the sky orange and black, and a product of the passive traditions that had allowed such evils to go unpunished, of a world that just turned its face from the fanatics and said they could not be responsible for what that white trash did.

But in the courtroom that day, something broke in young law student Doug Jones.

Or rather, something was welded in place.

He would get them.

He would get as many of them as he could.

He would, someday, assemble the broken pieces of a justice system that had left the families of those four little girls wondering just how much justice there was in a system that treated this horror with such nonchalance. He would scrape and dig and hound, and someday, someday

Almost four decades passed. His legal career had been impressive, and he had risen to become a U.S. Attorney based in Birmingham. The bombing case had always been with him, riding in his own conscience after all that time. If it was still hot to his touch, he knew how it must burn in the guts of the mothers, fathers, sisters, and brothers of the victims of September 15, 1963.

Others, some well-meaning, some thinking of his future, said let it lay.

Nothing is gained by digging all that old stuff up again.

He could hear it in his sleep.

Baxley had gone after them, people cautioned, and look what happened. He could have been Governor, but the old racists rose from their holes and helped vote him down.

Let it lay.

Let it lay.

I knew I just had to do something, Jones said a thousand times.

I was not in the courtroom the day Jones got the second bomber, an old Klansman named Tommy Blanton, piecing together faded and crumbling evidence and testimony. He read the sworn testimony of ghosts into the record. He plumbed the faded memories of old men and women.

And Tommy Blanton went to prison for the rest of his life. The South might not have changed greatly, but it had changed enough.

The next and final trial, against a defiant old man named Bobby Frank Cherry, was harder. What few witnesses Jones had for Blantons trial were now gone. The hard evidence had all but faded away, like an old photograph left in the sun.

But one piece of testimony stood out raw and jagged and mean. Cherry had bragged about it, to witnesses. He had believed himself safe, in the company of men who saw the world through the same dark lens.