CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

February 1, 2014

CHAPTER 1

A Loner Arrives on Campus

CHAPTER 2

The B&B Show

CHAPTER 3

My Spot on the Bench

CHAPTER 4

The Honeymoons Over

CHAPTER 5

When Orangemen Played at Manley

CHAPTER 6

Beasts of the East

CHAPTER 7

A League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

CHAPTER 8

The Pearl at the Center of the Orange

CHAPTER 9

General Sherman

CHAPTER 10

The Enigma

CHAPTER 11

Blue Chips

CHAPTER 12

The Kentucky Connection

CHAPTER 13

The Last Loss of the Old Boeheim

CHAPTER 14

Eternal Rivals

CHAPTER 15

Melo, G-Mac and the Big One

CHAPTER 16

A Call from the Hall

CHAPTER 17

The Four-Day Show

CHAPTER 18

The Twilight Zone

CHAPTER 19

The Bernie Fine Saga

CHAPTER 20

The End of the East

CHAPTER 21

One and Done

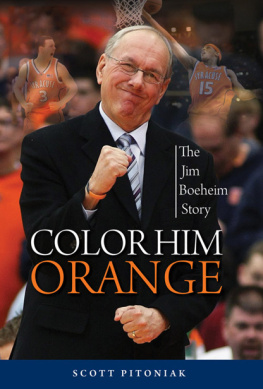

C ontrary to popular belief, being the son of a mortician does not make you weird or obsessed with death or anything like that. In my case, all that being the son of a mortician meant was that I didnt want to be a mortician. Neither did my sister Barbara, seven years my junior.

My great-grandfather started the Boeheim Funeral Home in Lyons, New York, in the mid-1800s, not because he had some perverse death fixation but because he made caskets at his furniture store and figured it was a canny expansion, the business of dying being invulnerable to market forces. The family sold it, but our name lives on in the Boeheim-Pusateri Funeral Home, which is still there on William Street, almost directly across from the elementary school. Im not sure why they left Boeheim on there. My oldest friend, Tony Santelli, says its because Boeheim is still a pretty good name around Lyons. I hope thats the case. If we have a bunch of losing seasons... well, I dont want to think about that.

We thought of ourselves as from upstate New York. Our sense of geography was pretty simple: Buffalo constituted western New York, Albany was eastern New York, and we were in the middle. Lyons was a great place to grow up, a kind of Leave It to Beaver town with a little more of an edge. The Boeheims were German in an Italian neighborhood, but honestly, its not like my family celebrated their cultural heritage much. My favorite food ran to spaghetti and meatballs, not sauerbraten.

The Lyons I grew up in had a population of about 5,000, but we didnt think of it as particularly small. It seemed just right. There were probably 70 of us who went from kindergarten through high school together. Everyone looked out for his neighbor, and nobody locked his door. On weekend mornings when I had trouble getting out of bedwhich was most weekend morningsTony would stroll in the back door, pass through the kitchen (with a view of the cold bodies in the embalming room off the other side) and run right up the stairs to my bedroom to wake me up.

The New York Central Railroad came through there (still does), and Erie Canal Lock number 56 is nearby, so there were plenty of jobs. Parker Hannifin had two plants there, and the Hickok belt company had one. I grew up in a prosperous Lyons, which is not the case today. You know how were always talking about the disappearing middle class? Lyons could be held up as a model. Tony and I first met because our parents belonged to a country clubnot an exclusive one, but one that drew mainly from a middle class that no longer exists.

My father, Jim, was a straight-shooting kind of guy, a solid businessman. The line I always fall back on is that my father had a good side but managed to keep it pretty well hidden. Maybe thats partly because he lived much of his life with the slug from a .22 lodged in his spine, the result of his brother having accidentally shot him when they were young. The doctors at the time didnt want to take a chance on removing it. As a result, one of his legs was shorter than the other and he had a kind of limp.

My father was a hunter and a fisherman, and much of our time together was spent going on bass trips and pheasant hunting. As I got older, I would fish alone, sometimes at midnight. The solitude never bothered me, and, no, I dont think it had anything to do with the solitude forever present in the embalming room. Its just the way I was. We did golf together, but we would rarely finish nine holes before one of us stomped off in anger. It was the same with any sport or gametable tennis, Monopoly, horseshoes. We both took losing very, very hard. Sister Barb has a word she uses to describe what happened when my father and I faced off in anything: fiasco.

I inherited more of my athletic ability from my mother, Janet, who was a good golfer and had played basketball in high school. She was probably responsible for my growing to six foot three, too, since she was five-eight, fairly tall for a woman in those days.

Despite how competitive my father was, and how much he resisted praising me, he and my mother attended every single high school and college game I played. When they couldnt get there for road games, the radio play-by-play was on in our house. My sister remembers my father, who mightve been entertaining guests or conducting a business meeting in the living room, saying to her about every two minutes, Barbara, could you go check the score?

There was only one person in the world who nailed a basket up in our backyard and added lights so I could shoot at any time: James Boeheim Sr.

I owe my parents a major debt for something else: my memory. They were national-class duplicate bridge players who traveled all over for tournaments, though Im not sure opponents were always glad to see my father. If you dropped the wrong card, he was the kind of guy who said, You made that same mistake five years ago. That gets old in a hurry.

Like many kids, I worked in the family business, and it didnt seem unusual to me that that involved picking up bodies. Somebody had to do it. The Boeheim hearse also pinch-hit as the town ambulance, so I occasionally went on runs to the hospital as well. One time, when I was 15 or 16, a woman delivered a baby when I was along for a ride.

But for me, it was never about undertaking or obstetrics. It was always about basketball. I was one of those kids shoveling snow off the driveway, which was spacious, since it had to accommodate the hearse and funeral parking. By the time I was five, I was already shooting a pair of socks through a flowerpot I put on the wall in the living room. When I was in third grade, I was already an avid fan of Lyons High, a wide-eyed kid who thought that Kenny Chalker, the team star, was the greatest player in the known world. When I was a freshman and sophomore at Lyons High, I refereed the high school intramural games, which provided one of my nicknamesSid, after Sid Borgia, the best-known NBA ref at the time. The other nickname was Heimer, after, of course, my last name.

I went to Rochester Royals games from time to timeabout 50 miles awaybut I grew up loving the Boston Celtics, probably because they were the dominant NBA team. I have a vivid memory of watching Bill Russell, who came late to the Celtics because of his participation in the 1956 Olympics, blocking what seemed to be every shot in one of his first games. I wouldve been 12 then. If there was a game on, I watched it. For some odd reason, the game of the week often featured Memphis or Bradley, the Missouri Valley Conference having magically figured out a way to infiltrate eastern TV screens.