The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

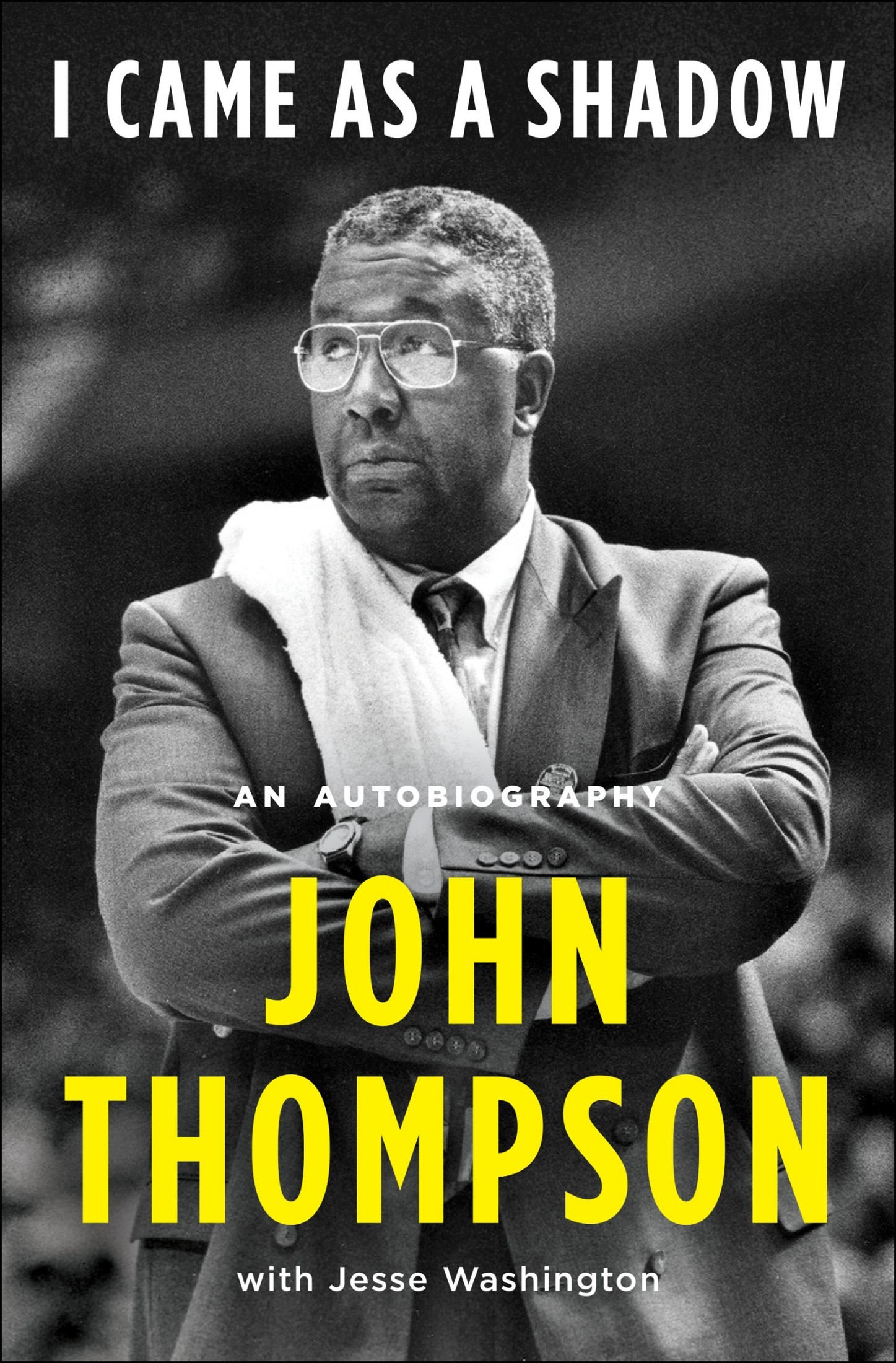

The door was unmarked. It opened into a tiny office, barely big enough for the mans substantial frame, and our feet almost touched as we sat alone together for the first time. The room had no windows, no trophies, only photos of people he admired and loved, from Rosa Parks and Nelson Mandela to Patrick Ewing and Allen Iverson. A small statuette of the Virgin Mary rested on his desk.

We were on the first floor of Georgetowns John R. Thompson Jr. Intercollegiate Athletic Center, down the hall from his larger-than-life statue. Coach Thompson made no small talk when I arrived; there was no conversational layup line to warm up for the writing of his autobiography. He started in a full-court press, flooding my recorder with a wide range of stories. His gaze was penetrating, challenging, and occasionally amused by all the things I did not yet understand. He focused on the time before he became basketball coach at Georgetown, when the only Black people on campus were servants and mascots, and the university had yet to acknowledge the fact that its very existence had been secured by the sale of 272 enslaved Black people.

Two years later, several months before the publication of this book, John Thompson died at age seventy-eight. The outpouring of testimonials to his legacy demonstrates how his impact on higher education, athletics, and Black empowerment remains deeply relevant today. Yet even many of his greatest admirers were unaware of the full meaning of his singular lifethe extent of the obstacles he faced, the mentors who taught him how to succeed, why he refused to play the role expected of Black people, what he believed we all must overcome in order to turn our tortured American history into triumph. These are the things he wanted people to learn through his life story, and why he periodically told me, I dont want this to be a book about basketball.

Soon after we met, Coach moved our sessions to another room at the athletic center, where we sat amid scrapbooks containing newspaper and magazine articles that chronicled his entire coaching career. But Coach had little interest in rehashing what happened in all those famous games. He cared most about the intellectual aspects of the game behind the gamethe layers of variables and barriers, mostly psychological instead of physical, that he encountered during his career. And he cared intensely about his players, whose well-being dictated his thoughts and actions. Almost every negative headline in those scrapbooks came from his mission to protect and educate his kids at all costswhile obtaining equality for Black people.

During countless hours of conversations over those two years, Coach told me on more than one occasion, We have to get this right, and he deliberated over every word on these pages to make sure they were exactly what he wanted to say. He knew this would be his final testimony, and how much it is still needed.

Thank you, Coach, for opening the door.

Jesse Washington

September 8, 2020

I always planned to be a teacher, not a basketball coach. I used basketball as an instrument to teach.

My classroom was the court.

When I say teach, Im not talking about how to run 2-2-1 zone press or the fast break, although we did those things quite well. I felt a responsibility to broaden my players perspectives, of the world and of themselves. I had to expose my kids to their own intellects and give them a sense of self-worth beyond their physical attributes. I tried to praise them for their minds as much as for making the quick trap off the inbounds pass. But I always knew the reason I had their attention was basketball. Basketball was my instrument to make them listen to everything else.

Basketball also became a vehicle for me to challenge injustices. I didnt think about it that way when I started coaching Georgetowns team in 1972. I just did what came naturally based on how I was raised by my mother and father, the environments that I lived in, and the amount of time I was exposed to certain things. I reacted based on heredity, environment, and time. It wasnt like I strategized or planned to be an outspoken person. If I thought my team, myself, or people in general were being treated unfairly, I tried to say something about it. Sometimes I did not speak up when I should have. Other times, I should have kept my mouth shut. But as I got further in my career, basketball became a way of kicking down a door that had been closed to Black people. It was a way for me to express that we dont have to act apologetic for obtaining what God intended us to have, and that we should be recognized more for our minds than our bodies. All this came out of the strong responsibility I felt to teach kids more than how to throw a ball through a hoop.

Too many Black kids are conditioned to seek recognition based on physical instead of intellectual attributes. We have to stop thinking about power as being able to dunk on somebody or lay somebody out on the football field. Real power is defined by the capacity to think and excel in various situations. Compared with physical abilities, intelligence places you in a better position for a longer period of time. Far more money is made sitting down than standing up.

These are some of the things I felt it was important to teach. But I have to be honest about my motivations. I also wanted to win basketball games. I wanted to win an awful lot. Lets not act like I was Saint John out there, only concerned with education and uplifting the race. Winning was incredibly important to me, and you best believe I was good at it.

People only listen to you if you win. I intended to be heard.

I knew that my success or failure would influence opportunities not only for other Black coaches, but for Black people in general. I couldnt be just a coach because my cause was not the same as most other coaches. My cause was more serious. I had to win because Black people didnt have the right not to be successful.

Years ago, I read a quote by Mahatma Gandhi that affected me deeply: Freedom is not worth having if it does not include the freedom to make mistakes. In other words, to be truly free, we must have the freedom not to be successful, too. When I arrived at Georgetown, I knew of only four other Black head basketball coaches at white colleges. If I didnt win, and win fast, I would have been run out of there and you never would have heard from me again. The next Black coach in line probably wouldnt have gotten hired, either. Most Black people, myself included, did not have the freedom not to be successful.

America is finally realizing that even today, after all that Black people have fought for and achieved, far too many of us are still not free.

As I finish this book, the nation is being torn apart by protests and riots over the death of George Floyd. This man did not have the freedom to make a tiny mistakeallegedly passing a fake twenty-dollar bill. I empathized with Floyd when I heard him cry out Mama! as he died beneath that policemans knee. I was a mamas boy growing up. The safest place I ever felt was in my mothers arms. The protests have forced everyone to confront a lot of deeper injustices, which is something I have always tried to get people to consider. Yes, Black people are being needlessly killed by police, but there are many ways of killing a person. You can kill people by depriving them of opportunity and hope. You can kill people by saying that society is equal, then starting a hundred-yard race with most white people at the fifty-yard line. Discrimination is a lot more complicated today than when I was growing up and they made Black people sit in the back. Trying to fight discrimination today can feel like shooting at ghosts.