Copyright 2009 by Timothy Egan

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Egan, Timothy.

The big burn : Teddy Roosevelt and the fire that saved America / Timothy Egan.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-618-96841-1

1. Roosevelt, Theodore, 18581919. 2. PresidentsUnited StatesBiography. 3. ConservationistsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Pinchot, Gifford, 18651946. 5. Forest conservationUnited StatesHistory. 6. Nature conservationUnited StatesHistory. 7. National parks and reservesUnited StatesHistory. 8. United States. National Park ServiceHistory. 9. Forest firesMontanaHistory. 10. Forest firesIdahoHistory. I. Title.

E 757. E 325 2009

973.911dc22 2009021881

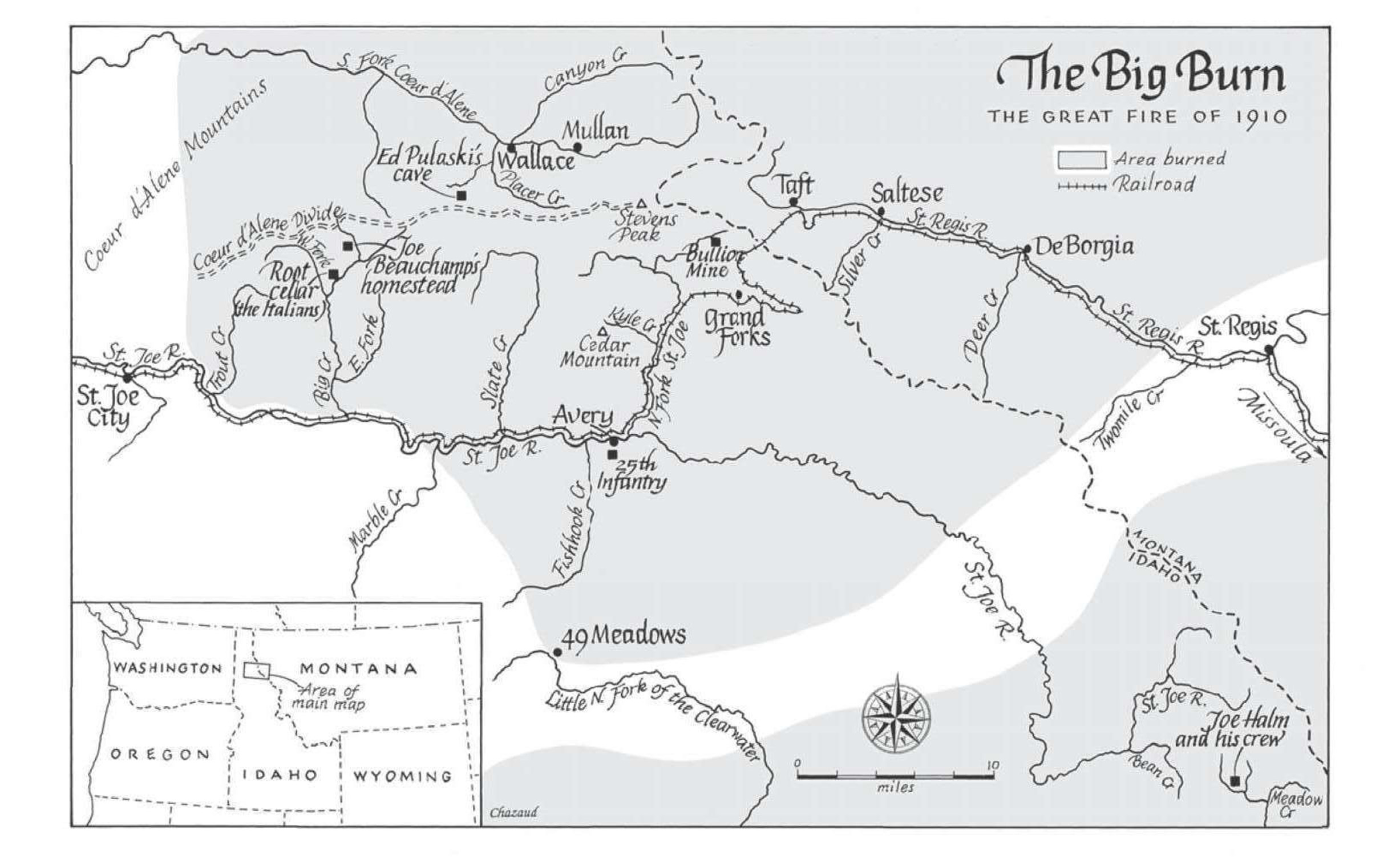

Map by Jaques Chazaud

e ISBN 978-0-547-41686-1

v5.0515

To Sam Howe Verhovek

Friend, editor, writer, and adopted son of

the Pacific Northwest, no bow-tied bum-kisser he

If now the dead of this fire should awaken and I should be stopped beside a cross, I would no longer be nervous if asked the first and last question of life, How did it happen?

NORMAN MACLEAN, Young Men and Fire

PROLOGUE

A Fire at the End of the World

H ERE NOW CAME the fire down from the Bitterroot Mountains and showered embers and forest shrapnel onto the town that was supposed to be protected by all those men with faraway accents and empty stomachs. For days, people had watched it from their gabled houses, from front porches and ash-covered streets, and there was some safety in the distance, some fascination evensee there, way up on the ridgeline, just candles flickering in the trees. But now it was on them, an element transformed from Out There to Here, and just as suddenly on their front lawns, in their hair, snuffing out the life of a drunk on a hotel mattress, torching a veranda. The sky had been dark for some time on this Saturday in August 1910, the town covered in a warm fog so opaque that the lights were turned on at three oclock in the afternoon. People took stock of what to take, what to leave behind. A woman buried her sewing machine out back in a shallow grave. A pressman dug a hole for his trunk of family possessions, but before he could finish, the fire caught him on the face, the arms, the neck.

How much time did they have until Wallace burned to the ground? An hour or two? Perhaps not even that? When the town had been consumed by flame twenty years earlier, it fell in a deep exhalepainted clapboards, plank sidewalks, varnished storefronts. Whoooommmppffffff! Then they did what all western boomers did after a combustible punch: got up from the floor and rebuilt, with brick, stone, and steel, shaking a fist again at nature. And since there was so much treasure being stripped from the veins of these mountains on the high divide between Montana and Idaho, they rebuilt in a style befitting their status as the source of many a bauble in the late Gilded Age. Italian marble sinks went into barber shops. Cornices were crafted of cast iron. Terracotta trim decorated bank windows. The saloons, the bordellos, the rooming houses, the mens clubs, the hotelsfireproof, it said on their stationery. Most impressive of all was the new train depot of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Designed in the Chateau style, the depots buff-colored bricks formed a Roman arch over the main window. Three stories, counting the magnificent turret, and shingled in green. The depot was an apt hub for a region that promised to produce more silver, lead, and white pine than any other on the planet.

It seemed like a toy city, a novice forest ranger said after he had crested the mountains by train and caught his first sight of Wallace, Idaho, clean and spotless, and very much up to date, with fine homes and fine people.

In the early evening, the young mayor, Walter Hanson, checked with his fire chief, and he summoned his assistant, and they said, yes, it was timesound the alarm! That was it; everyone knew they had to make a dash for the getaway trains. Women and children only, the mayor said, with a Victorian gentlemans reflex common even in the Far West. He deputized an instant force of local men to back him up. Troops were available as well, the negro soldiers of the 25th Infantry, I Company, who had just pitched a hurried camp on the Wallace baseball field after withdrawing from the aggressive front line of the fire. Over the years, they had chased Indians in the Dakotas, put down insurrections in the Philippines, and helped to establish civil order during western labor wars, but never in the history of the 25th Infantry had these Buffalo Soldiers been asked to tame a mountain range on fire. In a state with fewer than seven hundred blacks, the troops were greeted with curiosity and skepticism by polite citizens, scorn and open hostility by others. On Saturday, after they pulled back from the flames up high and regrouped on the baseball field, the retreat fed the scolds who said a black battalion could never save a town, much less fight a wildfire nearly as large as the state of Connecticut.

Even as the bell rang, the special trains were being fitted, with not enough space for half the town of 3,500 people. Rail workers stripped away cargo and some seats to make room for the exodus. The men could not leave, the mayor insisted; they must stay behind and fight. The elderly, the infirm, and little boys, of course, even those who looked like men, could go. Everyone else was told to get a garden hose and go up on their roofs, or jump aboard one of the horse-drawn fire carriages, or grab a shovel and get on a bicycle. Or pray. The mayor was asked about the jaildo we let the prisoners burn? Needing the manpower, he ordered the cells opened and the inmates sent to Bank Street, right in front of the courthouse, to form a human fire line. Only two would remain handcuffed, a murderer and a bank robber.

The evacuation was not orderly, not at all as the mayor had imagined days earlier when he first drew up plans with the United States Forest Service to save Wallace. People dashed through the streets, stumbling, bumping into each other, shouting rumors, crying, unsure exactly where to go. Some carried babies under wet towels. Some insisted on carting away large objects. It felt as if the town was under artillery fire, the mile-high walls of the Bitterroots shooting flaming branches onto the squat of houses in the narrow valley below. Between flareups and blowups, the hot wind delivered a continuous stream of sparks and detritus.

Earlier in the day, ashes had fallen like soft snow through the haze. At the edge of town, where visibility was better, people looked up and saw thunderheads of smoke, flat-bottomed and ragged-topped, reaching far into the sky. Then the wind had calmed to a whisper for the better part of an hour, a truce of sorts, and it seemed that the town might be spared. But at 5 P.M. , leaves on trees rustled and flags unfurled in slow flaps as winds picked up to twenty miles an hour. By 6 P.M. , telephone lines and utility wires whistled with another kick in velocity. And before the hour passed, big evergreens groaned at the waist and twigs snapped offthe air galloping to gale force, forty-five to sixty miles an hour, a wildfires best stimulant. So by nightfall, when the evacuation began, the blows were approaching hurricane force, extended gusts of seventy-four miles an hour or more. Everyone knew about Palousers, the warm winds from the southwest; they could pack a punch, though they were rare in the Bitterroots. But a Palouser hissing flames at high speedthis was a peek beyond the gates of Hell.

Next page