I met my wife on the way to a football game. At least thats my first clear memory of herour walk from Mary Markley Hall, across the Diag, down State Street, and finally to Michigan Stadium. We didnt start dating until basketball season. Yet long before we were joined in matrimony, we shared a love for the maize and blue. Its what got us started.

My romance with college football goes back farther than my romance with her. It begins in my early boyhooda period of indoctrination orchestrated by my father, who had attended the University of Michigan in the 1950s. When most other kids were learning their letters, he made sure that I could sing Hail to the Victors. For us, the Carter era isnt a reference to a troubled presidency in the late 1970s, but rather to a glorious era in which wide receiver Anthony Carter wore a winged helmet and caught touchdown passes under the watch of coach Bo Schembechler (of sainted memory). Our family celebrated Christmas, Easter, and all the other usual holidays. Then there was one more, on what was always the biggest game day of the year: the Saturday in November when Michigan played Ohio State.

When I first began to attend Michigan football games as a student, along with my future bride and more than one hundred thousand of our closest friends, I came to realize that these contests are more than athletic competitions. They are cultural rituals of deep significance. They not only unite a diverse campus of engineering students and English majors, but they also create a community of fans across a region and beyond. Michigans boosters can be young or old, black or white, alumni or high school dropouts. They can be well-groomed auto executives or lunch-bucket union guys. They can be flannel-wearing Yoopers from the Upper Peninsula or suburban trolls from metro Detroit. They can meet on the other side of the world. Conversations about the team are social icebreakersa way to form bonds between fathers and sons, colleagues at work, and strangers at parties. My marriage is not the only one that owes a debt to the game.

Love for a college football team, whether its the Tennessee Volunteers or the Texas Longhorns, is almost tribal. In some cases, such as my own, the affiliation is practically inherited. In others, its chosen. Whatever the origin, it has the power to form lifelong loyalties and passions. I still get chills thinking about the sound of the marching band when it plays our fight song and the roar of the crowd when our squad runs onto the field. The sensation is a close cousin of patriotism. On brisk autumn afternoons, my three main allegiances are to God, family, and football.

I didnt play football except as a pickup game in the backyards of my neighborhood or on the fields by schoolnever under the glare of Friday night lights. I know the sport primarily as a spectator. No other game has such a combination of brute force and pure grace, the crashing bodies at the line of scrimmage and the careful choreography of a well-executed play involving eleven men, and the infantry combat of a rushing attack as well as the air war of a passing assault. Theres a strong intellectual dimension as well. Baseball may bask in its reputation as a cerebral pastime, but no sport demands more meticulous planning or quick calculation than football. This is a pursuit not just for players and the fans who cheer them on, but also for coaches and the armchair generals who second-guess their every move. Little wonder that football has become the most popular sport in the United States, with millions of kids who play in youth leagues or high schools, millions of adults who fill stadiums on weekends and Monday nights, and millions of others who watch broadcasts from the comfort of home. Americans are probably more likely to know the name of their favorite teams starting quarterback than the name of their congressman. A good case can be made that they have their priorities straight.

Football has become such a central part of our national identity that we almost take it for granted. We expect the season to kick off around Labor Day, enjoy games as the air cools and trees shed their leaves, and anticipate college bowl matchups on New Years Day and the professional championship on Super Bowl Sunday. The sport has earned a permanent place in the rhythm of our lives. If we didnt have football, a lot of us wouldnt know what to do with ourselves.

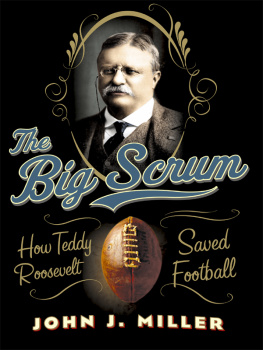

Yet there was a moment when football almost was taken away from usa time when its very existence was in mortal peril as a collection of Progressive Era prohibitionists tried to ban the sport. They objected to its violence, and their favorite solution was to smother a newborn sport in its cradle. It took the remarkable efforts of one of Americas most extraordinary men to thwart them.

Had the enemies of football gotten their way, they would have erased one of Americas greatest pastimes from our cultural life.

And maybe Id still be a bachelor.

O n an autumn afternoon in 1876, Theodore Roosevelt attended his first football game. He was a college freshman who had just turned eighteen. This young man who was destined for great things was enthusiastic about athletics and keen on seeing the newfangled sport of football in person. The previous afternoon, he and about seventy or eighty classmates had traveled from Cambridge, Massachusetts, to New Haven, Connecticut. They wanted to watch Harvard play Yale, in the second-ever football game between two of the greatest rivals in college sports.1

Roosevelt spent the morning of Saturday, November 18, touring the local sights with a Yale student he knew from his days of growing up in New York City. I am very glad I am not a Yale freshman, wrote Roosevelt. The hazing there is pretty bad. The fellows too seem to be a much more scrubby set than ours.2

The weather was scrubby as well, with overcast skies and gusting winds. Ships jammed the nearby harbor, driven in by gale-force blasts of cold air from the sea. By early afternoon, Roosevelt and his friends started to assemble for the game in Hamilton Park, where patches of mud would cause the players to slip and slide as they battled up and down the field.3

Before play began, the two teams met to discuss the rules. Football was in its infancy, still a work in progress, and only remotely like the sport into which it would evolve. There was no common agreement about many of its most basic elements. What number of men would participate? What would count for a score? How long would the game last? Teams had to make these decisions prior to the kickoff, like 21st-century schoolchildren who must set up boundaries, choose between a game of touch or tackle, and figure out how to count blitzes.

Harvard was confident of victory. Its players were more experienced than Yales and they had recently tasted success. Three weeks earlier, they had defeated a pair of Canadian teams in Montreal, shutting out both in the span of three days. Against Yale, Harvard was favored by odds of five-to-one.4 The previous year, the first time the two schools ever met to play football, Harvard had beaten Yale by a score of four goals to none. The game was even more lopsided than the score would seem to indicate. Harvard had dominated just about every aspect of the play. Yales men had looked tentative, as if they were confused about the most basic elements of the sport. In the sequel, many expected a repeat performance. Everybody accepted it as a foregone conclusion that Yale was destined to defeat, wrote the New York Sun .5