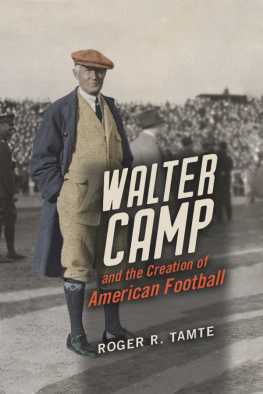

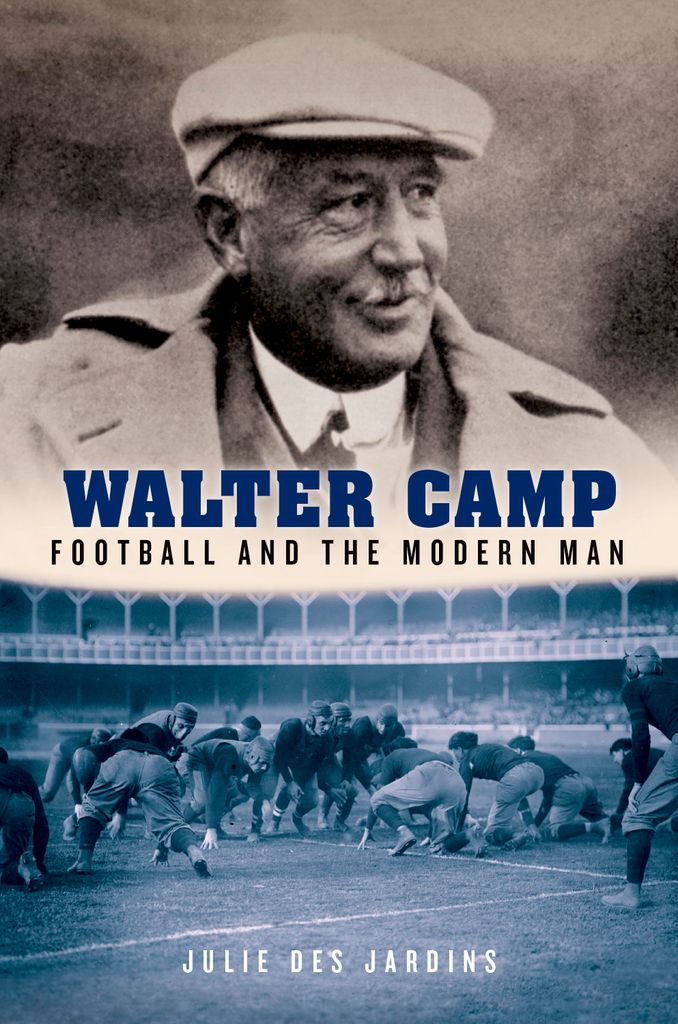

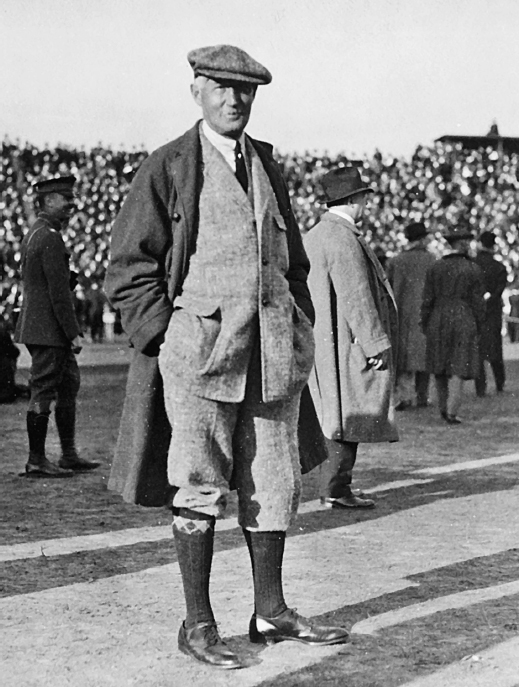

WALTER CAMP

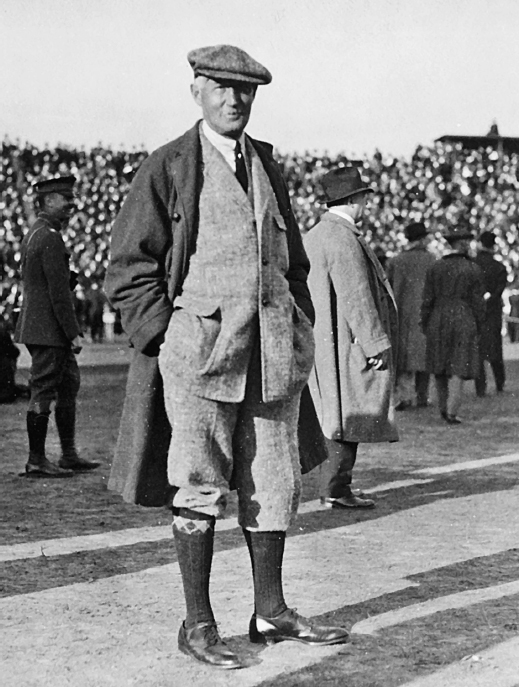

Frontispiece: Walter Camp at a football game, about 1920. Walter Chauncey Camp Papers, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University.

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

OxfordNew York

AucklandCape TownDar es SalaamHong KongKarachi

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityNairobi

New DelhiShanghaiTaipeiToronto

With offices in

ArgentinaAustriaBrazilChileCzech RepublicFranceGreece

GuatemalaHungaryItalyJapanPolandPortugalSingapore

South KoreaSwitzerlandThailandTurkeyUkraineVietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Julie Des Jardins 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Des Jardins, Julie.

Walter Camp : football and the modern man / Julie Des Jardins.

pages cm

ISBN 9780199925629 (hardback)

eISBN 9780190231255

1.Camp, Walter, 18591925.2.Football playersUnited StatesBiography.

3.FootballUnited StatesHistory.I.Title.

GV939.C34D47 2015

796.332092dc23

[B]

2015008469

To Bastianmy man in the making

To Chrismy convert to American football

CONTENTS

IN GRATITUDE:

Thank you, Nancy Toff, for taking on a book about football.

And Ana Calero for thinking that it made all the sense in the world for a feminist to write about the Father of Football.

And Ms. Jackie and the aftercare staff who took care of my kids so I could write. Thank you for giving me time to think.

And Carol Berkin, Thomas Heinrich, Vince DiGirolamo, and Clarence Taylor for being true friends as I grew disenchanted with CUNY. Im lucky that our friendship continues.

And Catherine Allgor, my long-distance guardian angel.

And Linda Voris and Despina Kakoudaki, friends and scholars of the best kind. Something tells me that your enthusiastic viewing of an entire Thanksgiving football game was one of your many gifts to me.

And Susan Warner, Stacy Krieger, Kate Foss, and Marlene Glifort, perfect permutations of mothers, friends, and professional women.

And Bert Hansen, Randy Trumbach, and Jed Abrahamian for engaging my ideas, however partially baked.

And my workout pals Linda, Eric, Jeff, and Sid for being salts of the earth after a day of writing.

And my students, who convinced me that a story about masculinity was as important now as ever, especially one told through football.

And my twin, Jory, for empowering me to think differently.

And my sister, Jenna, who reads everything that I write, and my brother, Joe, who probably already knows much of whats in these pages.

And Chris for giving me space and support on my angriest days and always.

And thank you, Mom, for thinking that everything I do is worthy. I love you more than words can say.

IN 1910, THIRTEEN-YEAR-OLD James Percy of East Cleveland, Ohio, sent a letter care of Boys Magazine to Walter Camp, the man known throughout the country as the Father of American Football. Percy was like other boys on YMCA and high school teams who had written Camp to clarify the definition of a scrummage, or a snap, or being held. One Chicago boy asked if a ball handed forward was considered a pass; in the early years of the game, it was unclear. In Percys case, the inquiries were not merely technical; he wanted to know how to train for high school ball. He described himself as physically weak...more or less what you would term a mollycoddle, and he wanted to change his image.

Mollycoddle was a familiar term to any American boy coming of age at the turn of the twentieth century. Bullies used it to terrorize, and President Theodore Roosevelt invoked it to characterize men who had grown soft and overcivilized in the industrial age. Males who rejected Roosevelts big stick diplomacy or his call to live a strenuous life were, in his estimation and rhetoric, milksops, sissies, pampered weaklingseffeminate and ineffectual men. Like Percy, they were mollycoddles, unprepared to lead in the modern age.

In his earnest attempt to become stronger and self-reliant, Percy decided to pick up football, a game he had never played a day in his life, but one that was popular all around him. College and high school competition was well established where he lived, so he could have turned to any number of men to teach him its technical aspects. And

Percy was not alone. By 1915, members of the Business Mens League of St. Louis paid Camp to give the talk What Shall We Make of Our Sons? Mr. Camp is one of the most distinguished and versatile men of our present time, touted the league. He thinks, talks and writes about the training of youth with keen appreciation of the responsibilities and difficulties of the father. It was true that Camp knew fatherhood firsthand: his son Walter Camp Jr. also achieved modest acclaim on the football field of Yale. But Camps development of football made him, in the eyes of St. Louis businessmen, a father for all American boys. That scoutmasters and YMCA directors also sought him out as an expert on the making of boys into men tells us that they viewed the game he invented as inextricably linked to the transformation.

All of this supposes that Camp was in fact responsible for the origins of American football, and yet the annals of history reveal no single inventor. In the late nineteenth century, football grew in popularity across the country so quickly that multiple football conferences and rules committees emerged to shape it non-uniformly, making it harder for a single man to assert supreme influence over it. For a time, universities like Berkeley and Stanford resorted to English rugby rules to curb the mounting criticism that American football was too brutal, a development that Camp could not prevent and may have inadvertently accelerated. Can we call a staunch advocate of amateurism the father of one of the most profitable team sports played in the world today?

Footballs place in the lives of American men is both due to and in spite of Walter Camp. His game took on meanings beyond what he intended, but that does not indicate that his influence was paralleled, or that it is not profound today. He, more than anyone, shaped the development of football and its popular image for fifty years. One of his former colleagues in the Intercollegiate Football Association likened him to an inventor with a patent on the game, making adjustments as he saw fit. A writer for the