Table of Contents

ALSO BY WILLIAM F. BUCKLEY JR.

God and Man at Yale

McCarthy and His Enemies

(with L. Brent Bozell)

Up from Liberalism

Rumbles Right and Left

The Unmaking of a Mayor

The Jewelers Eye

The Governor Listeth

Cruising Speed

Inveighing We Will Go

Four Reforms

United Nations Journal:

A Delegates Odyssey

Execution Eve

Saving the Queen

Airborne

Stained Glass

A Hymnal: The Controversial Arts

Whos on First

Marco Polo, If You Can

Atlantic High: A Celebration

Overdrive: A Personal

Documentary

The Story of Henri Tod

See you Later Alligator

Right Reason

High Jinx

Mongoose, R.I.P.

Racing Through Paradise

On the Firing Line: The Public

Life of Public Figures

Gratitude: Reflections on What

We Owe to Our Country

Tuckers Last Stand

In Search of Anti-Semitism

WindFall: The End of the Affair

Happy Days Were Here Again:

Reflections of a Libertarian

Journalist

A Very Private Plot

Brothers No More

The Blackford Oakes Reader

Buckley: The Right Word

Nearer, My God:

An Autobiography of Faith

The Redhunter

Let Us Talk of Many Things:

The Collected Speeches

Spytime: The Undoing of

James Jesus Angleton

Elvis in the Morning

Nuremberg: The Reckoning

Getting It Right

The Fall of the Berlin Wall

Miles Gone By: A Literary

Autobiography

The Rake

Cancel Your Own Goddam

Subscription

For Evan G. Galbraith, with affection

INTRODUCTION

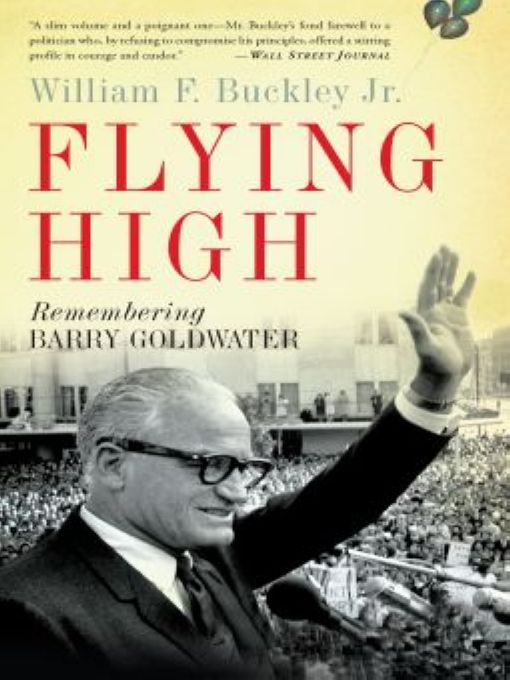

This slim volume tells a story. The storyteller is the author. No attempt is made to conceal this, and if the story were comprehensively retold, the authors role would probably be more conspicuous, not less so.

I am the founder of a conservative journal which took its place, very soon after its nativity, at the center of conservative political analysis in America. I, and others, expressed our resolve to resist collectivist solutions to problems at home and unprofitable accommodationism in foreign policy. Insights and formulations about which we felt strongly were being ignored by others on the political sceneat times suppressed, at times awkwardly misrepresented. What we did about it is the subject of this book.

We needed, for instance, a youth movement, and so we founded Young Americans for Freedom. We needed a national political figure around whom to consolidate, and so we transfigured Barry Goldwater. We needed to stimulate resistance to the endemic wiles of the Soviet bid for the world, and so we trained our eyes on what the Soviet legions were up to and on the movements of their central figures, especially Nikita Khrushchev, looking in on him moment by moment when he visited the United States.

We were all over the place and accordingly Flying High. At the same time we were earthily present in nooks and crannies of political and intellectual life in the two decades when all of this happened.

What was it like to edit National Review? We take the reader to an editorial conference with the magazines early architects, men and women of disparate inclinations and strengths. One of them is commissioned to ghostwrite a little book for Barry Goldwater expressing Americanist views, and seven months later he turns in the manuscript of The Conscience of a Conservative. It is an overwhelming success, and it shapes the thinking of the Republican Party, which nominates the authorGoldwaterfor the presidency.

This book recalls the many distractions that arose in the attempt to formulate wise and attractive positions for Goldwater as political candidate. And it revisits a private meeting at Palm Beach at which five people, including Goldwater, express themselves on such problems as the John Birch Society, which sought, with the best of intentions, to arrest productive right-wing thinking, substituting for it the hypothesis that our leaders were Communist dupes. This was here and there seriously contended, and some conservatives were seduced by the argument.

Senator Goldwater ultimately chose, in his campaign for president, to follow the advice of two or three men whose hold on politics was insecure. He knew all along that the fight to depose President Lyndon Johnson was political romance, but he gave in to the draft-Goldwater surge in order to infuse his party with a human and humane liveliness that would endure long after his defeat, awaiting formal validation with Ronald Reagan.

Reagan is not a major figure in Flying High, although we were very good friends and he was a faithful and outspoken partisan of National Review. I do touch on his contributions to the Goldwater campaign, especially the famous televised speech. But it seemed right to linger in this reminiscence at the side of Barry Goldwater as he pilots his plane down to Phoenix, the evening lights just coming on. There he would suffer the great political humiliation just ahead. It was assumed that his brand of thought would lie buried forever in the ash heap of American politics, but it would prove not to be so. One year later he would among other things be visiting National Review in New York, and enlivening thoseamong them the author of this very personal reminiscencewho had been standing by, doing our own things.

The reader is entitled to ask if the material here is factually reliable. Reliable is the perfect word in this context. The book is not strictly factual, in that conversations are reported which cannot be documented as having taken place word for word. Yet it is reliable in that these words might well have been spoken. There are zero distortions hereno thought is engrafted in anyone that alters the subjects character, or inclinations, or even habits of speech. If General Eisenhower cant be proved by divine auditors to have spoken the words here placed in his mouth, it is as certain as the ears on the readers head that such words were substantially those that were spoken, depicting Eisenhowers thoughts and expressions. There are one or two scenes which, though entirely congruent with what happened, are entirely fictitious, e.g., the description of the young aide on the airplane carrying Henry Cabot Lodge and Nikita Khrushchev to California. Such are there to enliven, and to be enjoyed.

It was a grand time we had, providing all that political experiences could yield, joys and sorrows, excitement and depression. It would have been wrong, and ungrateful, to keep all of this to oneself.

Prologue

Barry Goldwater traveled everywhere, and one time we found ourselves together in a remote place. I was less surprised to see the 1964 Republican candidate for president in Christchurch, New Zealand, eight years after his presidential campaign, than he was to see me. Barry Goldwater was a hardy naturalist, son of the sun of Arizona deserts, and a man of exploration and science. No tool of the trade, in his fields of interest, was unfamiliar to him, and none failed to attract his attention. The airplane was in his blood, and the radio, and instruments of magnification and miniaturization. He was perpetually curious about oddities of nature and geography, and he always had at hand the most alluring paraphernalia, cameras especially. Although I had flown in his airplane with him, pirouetting about the Grand Canyon, he teased me now, bound for the Antarctic, that my interest in natural wonders was syntheticthat I was drawn to other adornments of life. When, many years later, I performed a harpsichord concerto in Phoenix, a reporter accosted him, asking how, in the senators judgment, Mr. Buckley had acquitted himself. Goldwater replied, Wonderfully. Absolutely first rate. He paused. Of course, this is the first time I ever went to a concert.