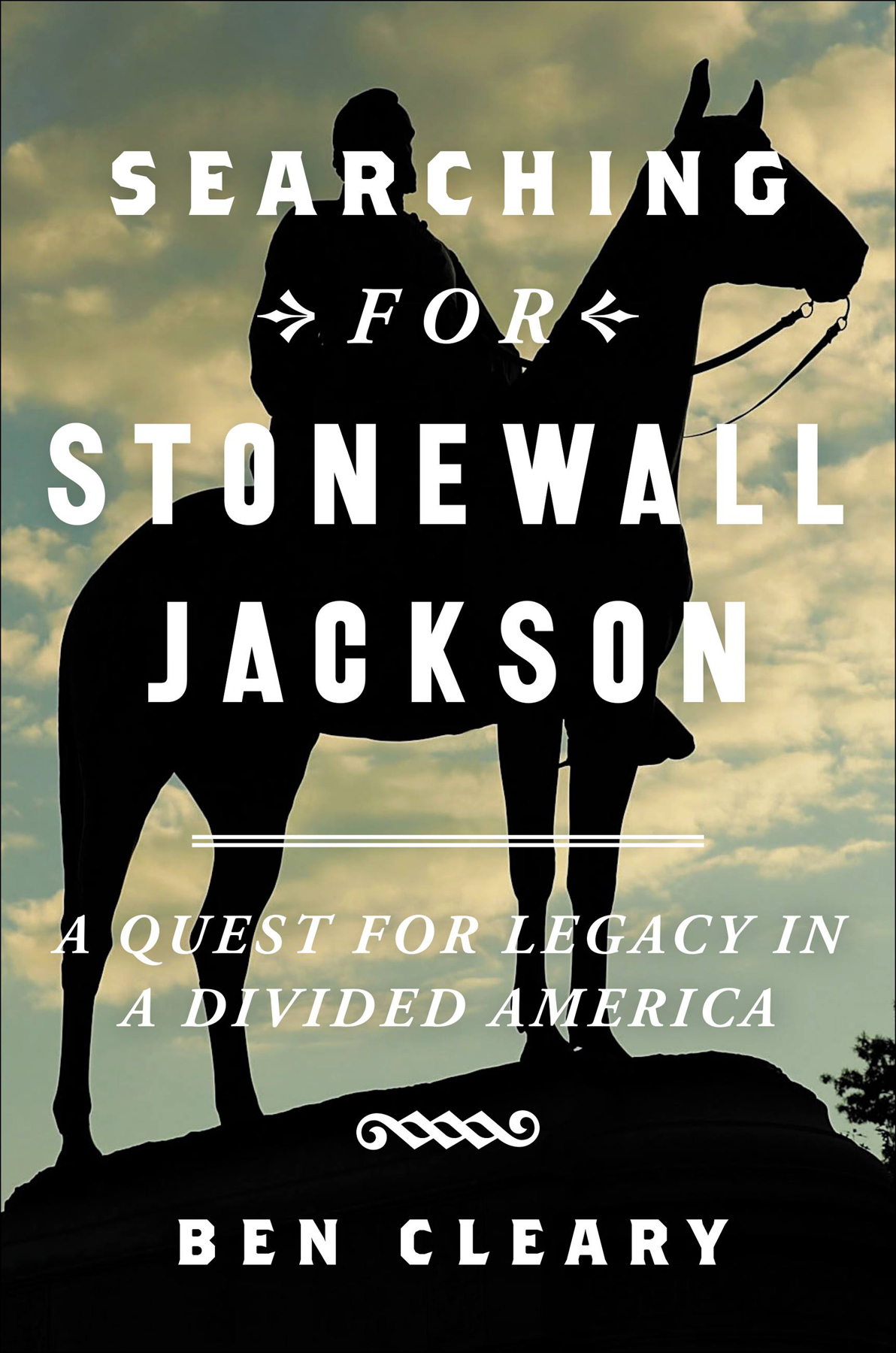

Copyright 2019 by Ben Cleary

Cover design by Jarrod Taylor. Cover photograph by Getty. Cover copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Twelve

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

twelvebooks.com

twitter.com/twelvebooks

First Edition: July 2019

Twelve is an imprint of Grand Central Publishing. The Twelve name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cleary, Ben (Ben C.), author.

Title: Searching for Stonewall Jackson : a quest for legacy in a divided America / by Ben Cleary.

Description: First edition. | New York : Twelve, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018048735| ISBN 9781455535804 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781549119910 (audio download) | ISBN 9781455535798 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Jackson, Stonewall, 18241863. | Confederate States of America. ArmyBiography. | GeneralsConfederate States of AmericaBiography. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Campaigns.

Classification: LCC E467.1.J15 C55 2019 | DDC 973.7/3092 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018048735

ISBNs: 978-1-4555-3580-4 (hardcover), 978-1-4555-3579-8 (ebook)

E3-20190606-JV-NF-ORI

To my wife, Catherine, and my son, Alexander

In gratitude for their love and support

I t was supposed to be the battle that would end the war. Lighthearted congressmen and other Washington dignitaries drove out in their carriages to the Virginia countryside to see the show. The summer weather was uncharacteristically temperate. July 21, 1861, was the perfect day for a picnic.

Irvin McDowells Union army made a leisurely progress to the battlefield, falling out for berry picking and discarding such weighty impedimenta of war as packs and even cartridge boxes. Their objective was Manassas Junction, a strategic railroad hub a few miles behind Bull Run: a slow, mostly shallow stream with a formidable southern bank where the Confederates were waiting. Each side had the same plan: Attack the enemys right flank.

McDowells actually worked. Feinting to his left near the spot where the Stone Bridge crossed the stream, he sent his attacking force around like a powerful right hook, crossing Bull Run to the northwest, then driving the Confederates southeast over the rolling Piedmont hills.

General Thomas J. Jackson was behind Bull Run on the Confederate right, waiting to participate in an attack that never materialized. Acting on his own, without orders, he moved toward the sound of the guns.

The northern Virginia traffic wasnt half bad. It only took one click for me to get through most of the lights on 234, the developer road that runs from I-95 northwest to Manassas. The site of the wars first big battle was also the first stop in my quest to gain a deeper understanding of Stonewall Jackson. Ive been fascinated with him for years, ever since I found out he marched down the road in front of my house. An incredible fighter, complex and contradictory, hes a puzzle Ive never completely put together. Id recently been asked to write a book about him. I relished the task.

I stopped at the towns small museum, parking in the shade before going inside to check out the exhibits and ask directions to Manassas Junction.

Inside, the fightings aftermath leapt out at me more than anything about the battle itself. Battles, actuallythere were two on almost exactly the same field. First Manassas in July 1861; Second in August 1862. Jackson was a major player in both.

In one exhibit, local resident Marianne E. Compton wrote about coming back into her house, which had been turned into a field hospital: All the lower part of the house was filled with wounded. We walked through a lane of ghastly horrors on our way upstairs. Amputated legs and arms seemed everywhere. We saw a foot lying on one of our dinner plates.

You see that? A young mother near me pointed out a cannonball to her pre-kindergarteners. Your granddaddy used to find those and roll them down the driveway. Then, more to herself than to her kids: I guess he should have saved them.

I purchased a Manassas fridge magnet. Neither the cashier nor the docent knew the location of the junction. Less than a mile away, the reason for the town and the reason for the battleit was like a tour guide in Rome not knowing the location of the Coliseum.

Lived here all my life and never been to this museum, the young mother told them as I was leaving.

Look out for your left, your position is turned, Captain Edward Porter Alexander had signaled Colonel Nathan Shanks Evans when he saw a strong marching column crossing Bull Run at Sudley Ford.interposed his small900-manforce in front of 20,000 advancing Federals, buying time but ultimately being beaten back, as were other holding actions by Brigadier General Barnard Bee and Colonel Francis S. Bartow. The Confederates retreated from Matthews Hill, over Buck Hill, and up Henry House Hill, outnumbered and dispirited.

Jackson, on the Confederate right, moved here and there in response to confusing orders from the excitable General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, the Hero of Sumter, who shared command with General Joseph E. Johnston. Finally intuiting that the fight was elsewhere, Jackson marched his 2,800 men to Henry House Hill, arriving there around noon. Southerners retreated past him as he placed his men behind the crest of the hill, an ideal defensive position.

General Bee rode up. The enemy are driving us! he told Jackson.

Then, sir, we will give them the bayonet.

The shade had moved from my car, but the heat that came out was only moderately ovenlike when I opened the door. Perfectly evocative of the battle: a mere eighty degrees, mild for a Virginia summer, and a great day for the spectators who had come out from D.C. to watch the saucy Rebels get whipped.

As I drove I reflected on the young mothers grandfather and his cannonballs, and on all the other stories Id heard about exploding Civil War ordnance. A history teacher at the high school near my house lost a couple of fingers when he was drilling out a shell to remove the powder so he could sell the artifact through the mail. He was lucky: In 2008, a relic hunter named Sam White lost his life when a shell he was disarming exploded, sending shrapnel into him and into the porch of a house a quarter of a mile away.