Contents

Guide

ALSO BY CHRISTIAN B. KELLER

Southern Strategies: Why the Confederacy Failed

Pennsylvania: A Military History

(with William A. Pencak and Barbara A. Gannon)

American Civil War: The Definitive Visual History

(with Wayne Hsieh, Robert Sandow, et. al.)

Chancellorsville and the Germans:

Nativism, Ethnicity, and Civil War Memory

Damn Dutch: Pennsylvania Germans at Gettysburg

(with David L. Valuska)

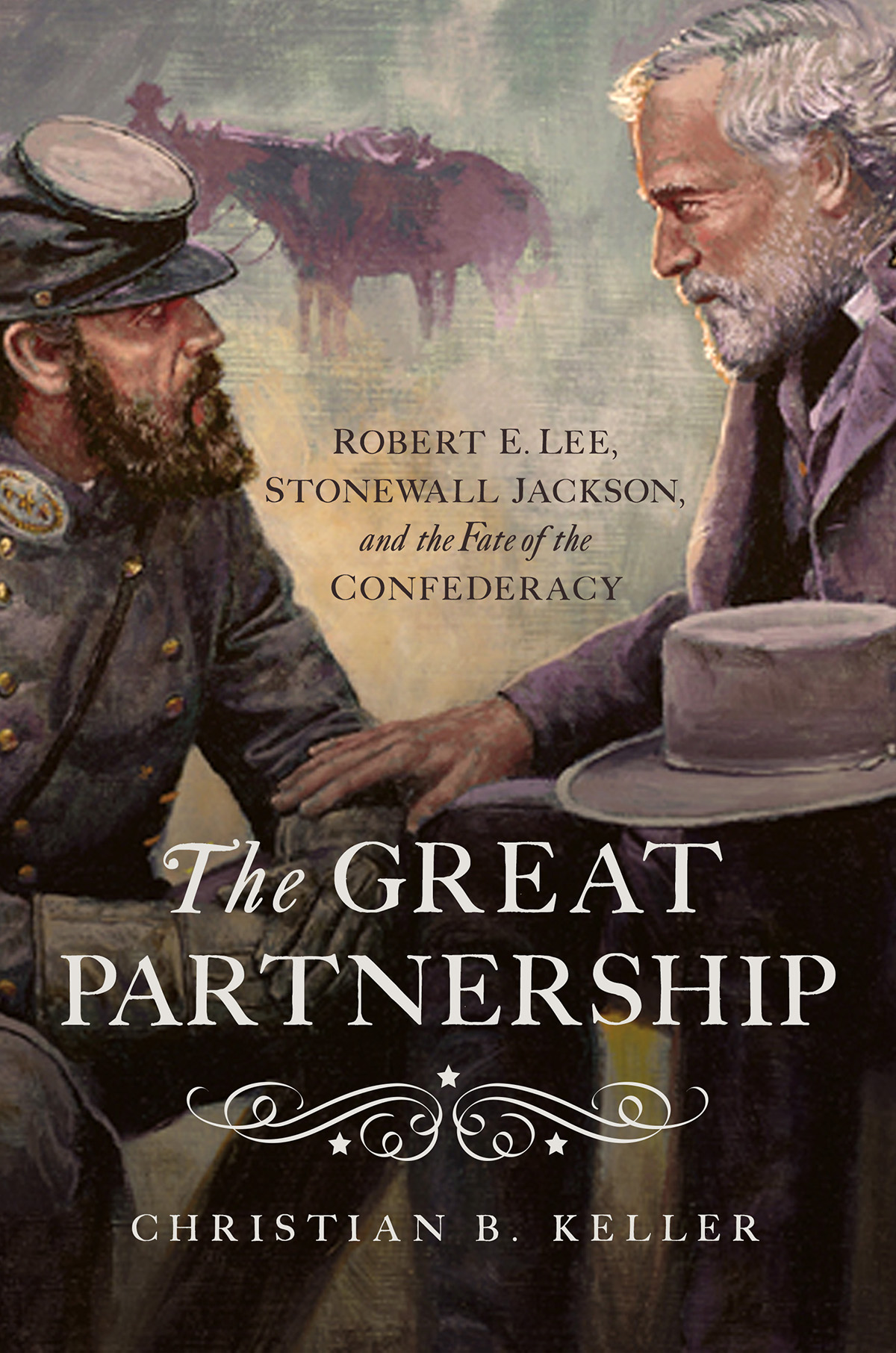

The GREAT PARTNERSHIP

Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and the Fate of the Confederacy

CHRISTIAN B. KELLER

THE GREAT PARTNERSHIP

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 Christian B. Keller

First Pegasus Books cloth edition July 2019

All maps by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All historical interpretations expressed in this book are solely the authors,and do not officially reflect or represent those of the U.S. Army War College,the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

ISBN: 978-1-64313-134-4

ISBN: 978-1-64313-173-3 (ebk.)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

For Kelley, and for Him

who guides my way

CONTENTS

T he late afternoon sun of May 10, 1863, was warm and pleasant, filtering through the young trees of the Virginia wilderness and creating a patchwork quilt of bright and dark spots on the forest floor. Here the light focused on a young fern, struggling to unfold itself into life, there it landed on a burned corpse or newly dug grave. Spring had come to central Virginia, but so had the war. Shattered rifles, shell fragments, broken canteens, and even the jagged remains of a drum littered the sides of the Richmond Stage Road, down which a small group of men were galloping full speed toward Fredericksburg. Those men had just been at the home of Thomas Coleman Chandler, who lived in a hamlet on the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad called Guineys Station. All that Sunday, they waited outside a small frame house on his estate and prayed for the man lying on the bed inside, offering supplications to the Almighty that he may be spared and return to duty. At 3:15 they found out that their prayers, and those of thousands more in the Army of Northern Virginia, had not been answered. General Thomas Jonathan Stonewall Jackson was dead.

Just the day before, the ailing leader dispatched his friend and corps chaplain, the Reverend Beverly Tucker Lacy, from his bedside to army headquarters near Fredericksburg. His mission was to conduct Sunday morning worship for the troops, as usual. Lacy preferred to stay, but Jackson insisted: the spiritual welfare of the men was paramount, regardless of what happened to him. The chaplain dutifully complied, leading the service on the 10th to a flock of 1800 soldiersand their army commander, Robert E. Lee. The great victory at Chancellorsville had been achieved primarily by Jacksons smashing flank attack on May 2, and now, at the height of his military success, Lee faced the possibility that his most trusted lieutenant and adviser might soon leave his side. Hearing of Jacksons worsening condition, Lee asked Lacy to express my affectionate regards, and say to him: he has lost his left arm but I my right arm. That was three days ago, when Jackson, his amputated arm healing nicely, had first displayed the troubling signs of a secondary infectionpneumonia. Now, despite fervent prayer and the best medical care in the Confederacy, Lacy had to admit to the commanding general that the end was near. The normally stoic Lee was surprised and visibly shaken at the turn of events. Surely General Jackson must recover, he told Lacy before the church service. God will not take him from us, now that we need him so much. His faith in his subordinates recovery seemingly strengthened by the chaplains sermon, Lee approached Lacy afterward and said, I trust you will find him better. When a suitable occasion offers, tell him that I prayed for him last night as I never prayed. These were brave words spoken by a brave man and devoted Christian, but Lacy saw through them. Lee could say no more in sight of the troops, and quickly turned away in overpowering emotion.

The riders, their horses fatigued at the long, hard run from Guineys Station, reined in at Lees headquarters about 5:00 and, hats in hand, approached the commanding generals tent. How exactly they conveyed their disturbing news, and what reaction Lee may have exhibited, is unknown, but the response from the soldiers in the ranks was immediate as the word spread. The sounds of merriment died away as if the Angel of Death himself had flapped his muffled wings over the troops. A silence profound, mournful, stifling, and oppressive as a funeral pall descended over the camps. Grizzled veterans of The Seven Days, Antietam, and Fredericksburg, some of whom had even fought with Jackson in the Valley, cried like babies. The shock to the living body of the army was palpable, according to this eyewitness. Another remembered, that evening the news went abroad, and a great sob swept over the Army of Northern Virginia; it was the heartbreak of the Confederacy. Indeed it was. Lee managed to restrain his own immense sadness in a simple message to Richmond. It becomes my melancholy duty to announce to you the death of General Jackson. He continued for a few brief sentences that described the transport of the body to the capital and then abruptly ended the wire. The next day, he issued General Orders No. 61 to the army in an attempt to assuage the grief hanging over it, but the messages tone left no doubt that Lee himself was still in shock: The daring, skill, and energy of this great and good soldier, by decree of an all wise Providence, are now lost to us. But while we mourn his death, we feel that his spirit still lives, and will inspire the whole army with his indomitable courage and unbroken confidence in God as our hope and our strength.... Let officers and soldiers emulate his invincible determination to do everything in the defense of our beloved country. Having duly erected this bold public front for the benefit of others, privately the army commander could not check his emotions. When he attempted to speak about Jackson to General William N. Pendleton that same day, Lee broke down in tears and had to excuse himself. The strong religious faith that helped cement the bond between Lee and Jackson doubtless comforted Lee now in his moment of greatest despair, and he wished the entire army to know its palliative effects. Yet his prayers and those of countless others had not saved Jackson, and his death left a great voidone with strategic consequences for the cause Lee defended. Privately he confided to his son, Custis, It is a terrible loss. I do not know how to replace him. On May 11, President Jefferson Davis probably reinforced Lees dread with a simple telegram: A great national calamity has befallen us. Faith would help Lee move forward personally, but the death of Jackson was a professionally mortal blow from which the Confederate chieftain, and the Confederacy, would never recover.