Contents

Guide

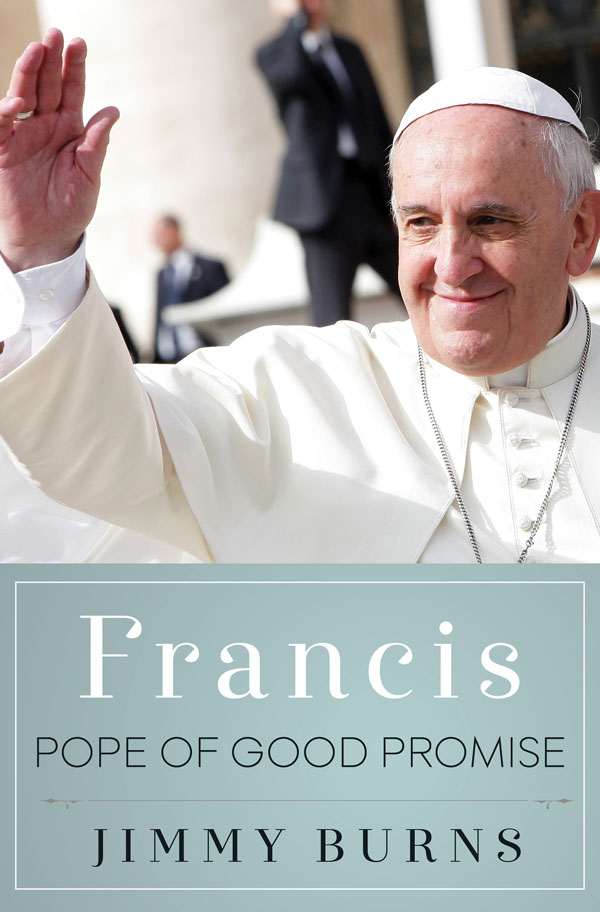

Francis,

Pope of Good

Promise

Jimmy Burns

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Kidge, Julia & Miriam

And for Fr Nicholas King SJ

Prologue

First Engagement

From the moment Pope Francis stepped onto the balcony of St Peters Basilica for the first time on 13 March 2013, a global audience caught a sense that not only the Catholic Church but the world at large could be entering a new spiritual as well as political and social age. Shunning the red shoes and mozzetta (shoulder cape) worn for the occasion by his predecessors, he was dressed only in the white papal cassock with a pewter cross around his neck. The sanctimonious pomp and circumstance that had characterized the Vatican for as long as most people could remember evaporated as Francis, with a simple gesture, bid everyone a peaceful Bona sera and asked the tens of thousands of people gathered in the square to pray over him before he gave his first Urbis et Orbi blessing to the city.

His appearance surprised many. While the winning cardinal was widely believed to have come second in the 2005 conclave, he had barely figured in the predictions as to who would succeed Pope Benedict XVI. My knowledge of the elected Jorge Bergoglio, the only ordained Jesuit among the collegiate cardinals, was at the time too full of apparent contradictions to form a firm opinion as to whether the choice had been inspired. What I had reported of the Argentine Churchs complicity in human rights violations and its support for the military juntas invasion of the Falklands Islands made me wary of the appointment of a cardinal of Buenos Aires as the new leader of the worlds 1.2 billion Catholics. Yet, within hours of his election I found myself bombarded with enquiries and journalistic assignments from both sides of the Atlantic, which forced me to draw more fully on memories and sources from my Jesuit education and from my years as a journalist in Argentina. This book has its roots in those preliminary researches that shed light on the extent to which Bergoglio had been shaped by the politics and society of the country into which he was born, the holy order of which he had chosen to become a member, and the example of the radical and universally popular Francis of Assisi, the thirteenth-century saint whose name he adopted on becoming pope.

In the days following his election, there would be further signs of Bergoglios simplicity that seemed to mirror the first apostles and the leader that inspired them. Francis chose as his home the Domus Sanctae Marthae, the hotel adjacent to St Peters Basilica used by clergy and cardinals, rather than the privileged privacy of the Vaticans Apostolic Palace. He declared that the thirty papal rooms he had been assigned by right were an excessive luxury he was happy to do without. During his first Holy Week as pope, he washed the feet of young male prisoners and Muslim women, before heading into the crowds, made up of all cultures and ages, with the selfless engagement of a universal pilgrim. Not since Pope John XIII appeared on the scene half a century earlier had a new pope opened the windows of the Church in such a way as to let in some much needed fresh air. Nevertheless people could still only guess at where it all might be leading towards. The jury was out. More time would have to pass before a clearer picture could emerge of Bergoglios life and the Francis papacy in action.

It was on a bright and mild Wednesday morning in early November 2013 in Rome one of the last balmy days of autumn before the winter chill set in that I caught up with Pope Francis in the early stages of his papacy. Armed with a ticket and advice provided by friends from the Catholic organization Opus Dei (for the record, I am not a member!), I turned up in a still relatively empty St Peters Square and positioned myself in the front row of the papal route. Even if I stood no chance of talking to him properly, I would come face to face with my subject.

Within an hour the square was packed and I was barely holding my post, penned in between an Argentine family and a group of equally excitable young Italian students. On either side of the papal route, there was a huge multicultural and international crowd, with people waving their national colours or some emblem or poster identifying their college, school, seminary or association. Most seemed to be Catholic and either Spanish- or Italian-speaking but there were many exceptions judging by the other languages I heard and other faith groups I glimpsed. In the excited and cheerful crush, I noticed a young Italian couple, with the woman gently rocking a three- or four-month-old baby boy in her arms. They were several rows back and stood not a chance of getting anywhere near the papal route so I called out to them and suggested that, when the time came, they pass the baby along the rows and I would hold him.

And so it came to be that when the Popes open-roof truck turned into the square and started moving in my direction I found a baby in my arms. He had been passed gently but purposefully from one row to the other, like a parcel on special delivery. I owe it to the baby that Pope Francis there and then gave me more time than I had otherwise expected. Seeing me with the child, he ordered his driver to stop so he could stoop over to kiss and bless the infant as I raised him up. In the seconds that followed, it was as if the whole square had disappeared and I was there, with the baby, alone with Pope Francis, enclosed in the moment. There seemed something providential, if not miraculous, that I of all people was holding somebody elses baby. You see, I was told from an early age I could never father a child of my own once a dark cloud in my life, but one that eventually lifted when my wife and I took a joint decision to adopt, bringing enduring delight into our lives. The Pope would not have known this, but his eyes and mine met, and in an instant I felt recognized and reassured, all stress and division dissipated. I was drawn to what I can only describe as the inner goodness of the man as he smiled and blessed me too, before he moved on across the square, where thousands awaited him.

When I had followed him that summer on his first papal pilgrimage beyond Europe, to Brazil for World Youth Day I had observed similar encounters in which Pope Francis seemed to touch an individual in the crowd with a sense of extraordinary personal engagement. My experience on that autumn day in Rome would chime with that of many others during his first years in office.

One of the phrases Pope Francis uses to explain transformative encounters is the Buenos Aires slang expression nos primerea. Literally translated it means: he prioritizes me. Its a term that he picked up years ago from the terraces of his beloved San Lorenzo football club. Its often used by Argentine fans to talk of a good football move that ends in a goal a move that anticipates you or beats you to it.

My own transformative encounter with the Pope provides a fitting image of the person Catholics are brought up to believe is Christs Vicar on earth, but this portrait of Bergoglio and Franciss world past and present tells the story of a complex man. My subject is no picture-book saint but a very human priest who struggled to be a true witness of his faith in challenging times. In circumstances he neither sought nor foresaw he found himself handed the highest office at a time of institutional crisis, not just for the Church but for long-established institutions worldwide, from banks to political parties.