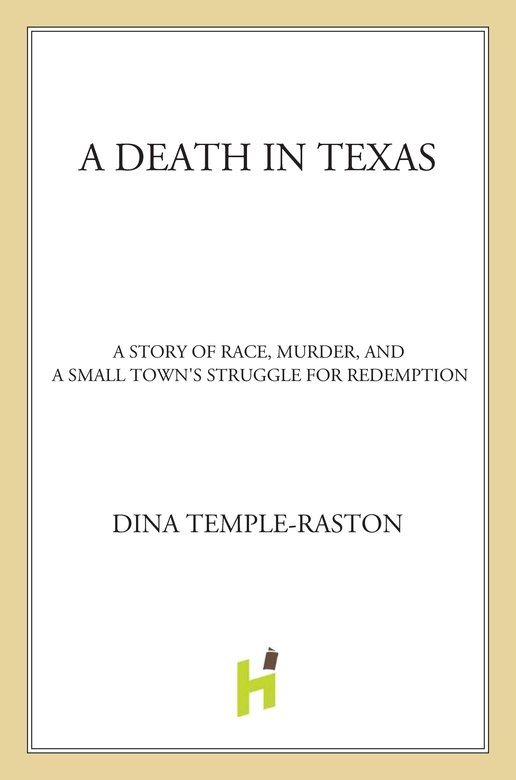

MY DEEP THANKS to all those who took the time to help me with this task, whether it was providing information, adding insight, offering advice, or patiently listening to yet another story about my latest trip to Jasper. This project spanned three years: it began several months after the murder and was finally completed in the middle of 2001.

By definition, a book about ordinary people in a small Texas town depends on the kindness of strangers. My greatest debt is to the people of Jasper who allowed me to pepper them with pointed questions about a subject that makes everyone uncomfortable: race. They shared their feelings about the murder, prejudice, and the decline of Jasper with unsparing generosity. They took me into theirhouses, introduced me to their children, and allowed an outsider to rummage around in their lives. Without them, this book would never have come into being. While I know many Jasperites will not agree with the conclusions I have drawn about their town, I hope they feel that I have been fair in trying to portray their trials through a difficult time.

In particular, I would like to thank Sheriff Billy Rowles, his wife, Jamie, District Attorney Guy James Gray, Reverend Kenneth Lyons, Ronald King, Vander and Christine Carter, Joe Tonahill, C. Haden Sonny Cribbs, and William Seale for always making time for me when I came to town. In particular, Billy Rowles and Guy James Gray allowed me to bounce my theories off them and helped me calibrate my conclusions. I was in Jasper for a total of more than four months over the course of two years, and I appreciated very much the hospitality of Janie Sheffield and David and Pat Stiles. They treated me like a member of the family and were always excited to see me when I arrived.

My agents, Joy Tutela and David Black, provided unending enthusiasm, keeping the book alive when despair threatened to set in. Joy Tutela fell in love with the proposal from the start and was always full of ideas and encouragement as she shepherded it to its conclusion. She embodies all the qualities the best agents are supposed to have.

My editor at Henry Holt, Elizabeth Stein, is one of the smartest people I know. Her good humor, ability to guide gently, and editorial instincts were an unbeatable combination for this first-time author. Joan Didion, in her essay about her editor, Henry Robbins, said the best editors gave the writer an idea of themselves, and that image enabled the writer to sit down and write. A good editor not only [has] to maintain a faith the writer shares only in intermittent flashes but also [has] to like the writer, which is hard todo. Writers are only rarely likable. Liz and I developed a great friendship, and she is a pleasure to work with. She is everything a great editor is supposed to be.

My copy editor, Vicki Haire, did a meticulous job in finding my errors of commission and omission. My colleague at USA Today, George Hager, was kind enough to read the manuscript with a copy editors eye to ensure that I didnt make mistakes that would be an embarrassment later. He is one of the kindest, most intelligent people with whom I have ever had the pleasure to work, and his good humor throughout this project will always be appreciated.

Many friends read the manuscript, in whole or in part. Bob Mautner, Linda Kulman, Robin Meszoly, Gary Rawlins, Denise Pellegrini, George David, Skip Thurman, Campbell Brown, and Jim Angle provided helpful suggestions and guidance as this northerner tried to capture life in the South. Encouragement and support from the editors at USA Today, in particular Mike Clements, Jim Henderson, and John Hillkirk, who gave me time off to complete the manuscript, were invaluable in getting the book finished.

My deepest thanks go, finally, to the people who supported me in this project, including Bob Mautner and that friend who always makes me try harder. Last but not least, my writing professor at Northwestern University, Joseph Epstein, has my gratitude. A mentor and a friend for more than fifteen years, he has always had a knack of saying just the right thing at just the right time. I would not be a writer today if it were not for him.

DINA TEMPLE-RASTON was a longtime White House reporter for Bloomberg, Business News before becoming a correspondent for USA Today. This is her first book. She lives in Washington, D.C.

June 2001

BILL KING was delivered to death row in Livingston, Texas, in February 1999. The remainder of his existence, until he is put to death in Huntsville, will revolve around three meals a day, showers, short exercise periods, and waiting. Two years after the murder, on June 7, 2000, the Byrd family filed a wrongful death lawsuit against King, Brewer, and Berry. King answered the suit by saying that he was innocent, despite the evidence against him. At the same time he wrote a letter to the Jasper County district clerks office asking the court to waive his automatic appeals.

Ive come to the realization that I cannot do everything myself with regards to legal matters no matter how much diligence, effort or time I devote to my plight, King wrote. And its becomeincreasingly obvious that court appointed lawyers in this state only give a damn about themselves and saving face with the courts. To put it mildly, I simply dont care to pursue these cases any longer. Kings letter was somewhat academic. Texas law mandates that death sentence appeals continue regardless of a prisoners wishes.

Several months later, on October 18, 2000, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals upheld his death sentence. In a unanimous opinion, the nine-member court rejected all the challenges to his conviction. Kings lawyers had argued there was insufficient evidence to prove that Byrd had been kidnapped on that June night. King said the evidence proved he was a racist, not a kidnapper or murderer. The court disagreed. It concluded that Kings guilt was supported by DNA evidence. Whats more, it said, there was extensive evidence of [Kings] hatred for African-Americans. Kings letters to the media and his kites to Russell Brewer could have been construed by the jury as an admission of guilt, the court said. Guy James Gray was right; King had written himself to death.

In December 2000, a Bill King Web site appeared on the Internet. Posted with a link to the Lamp of Hope Project, a nonprofit organization that provides a forum for death row inmates to post their writings, seek money, and find pen pals, the Web site outraged Jasperites. The Web page solicited donations to the John King Defense Fund at the First National Bank in Jasper. Ronald King said he did not know how much money was in the account, but he sent his son money from the bank when he needed it.

As of mid-2001, a date of execution has yet to be set.

RUSSELL BREWER was to spend the rest of his days on Livingstons death row as well. He and King resided in different wingsof the prison. And while it was unlikely that the pair would have had much of an opportunity to communicate, prison officials said they could have been sending kites to one another. No kites had been intercepted to date. Brewers case was also on automatic appeal, and by May 2001 he had yet to have an execution date assigned.

SHAWN BERRY was kept in isolation at Livingston prison as he began serving his life sentence. He would be eligible for parole in 2039. His four-year-old son, Montana, was not permitted by prison officials to touch his father. Montana lived with his mother and grandparents in Newton County, Texas. In April 2001, an appeals court began deliberations on whether to grant Berry a new trial. His lawyers argued the case before the Ninth Court of Appeals in Beaumont, Texas, saying Berry should never have been tried in Jasper. Their eighteen-point request for an appeal was filed more than two years after the murder, in August 2000. They argued that all the media coverage made it impossible for Berry to receive a fair trial in Jasper.