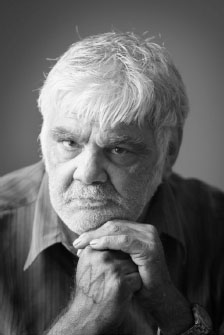

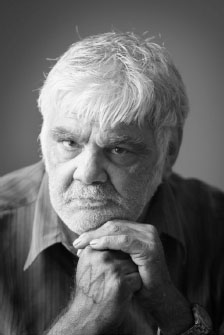

For Bruce Trevorrow (19562008)

First published 2019 by

FREMANTLE PRESS

Fremantle Press Inc. trading as Fremantle Press

25 Quarry Street, Fremantle WA 6160

(PO Box 158, North Fremantle WA 6159)

www.fremantlepress.com.au

Copyright Antonio Buti, 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher.

Cover photographs: sunlight on floor, Oote Boe Ph / Alamy Stock Photo;

salty lagoon in Coorong National Park, Ingo Oeland / Alamy Stock Photo

Cover design: Nada Backovic, www.nadabackovic.com

Photograph of Bruce Trevorrow, : Stuart McEvoy /Newspix

Printed by Everbest Printing Investment Limited, China

| A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia |

A Stolen Life. ISBN 9781925815122 (epub).

Fremantle Press is supported by the State Government through the Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries.

Publication of this title was assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

It was May 1994.

I had been working at the Aboriginal Legal Service of Western Australia (ALS) for only a few days when a senior lawyer handed me a file and said, This is yours now.

I sat at my desk and opened the manila folder. There was one typed paged inside. It had the clients name and address, followed by a few paragraphs of what appeared to be an abbreviated life history. I read that when the client was aged six, he had been separated from his parents and placed in a mission. He stayed there until he went to work on a farm at fifteen years of age. Life after that was filled with broken relationships and alcohol abuse.

I was unclear what to do with the file.

Another week went by before the chief executive of the ALS, Robert Riley, came to my office. He asked me to commence a project interviewing Aboriginal people who as children had been separated from their parents and placed in government-run receiving homes, in religious missions or with foster carers. This project turned into a two-year assignment of interviewing and collecting stories from over 500 people (I personally interviewed around 250 people) and writing two reports, Telling Our Story and After the Removal. These reports became the ALS submission to the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families.

Until that day when Rob gave me a thumbnail sketch of this history, Id had no idea of this official government policy of removing Aboriginal children from their families. I am not proud of that fact, but I also wonder why this history was missing from my school curriculum.

When I moved into legal academia in 1997, I continued my research into what has become known as the Stolen Generations. I also completed a doctorate on guardianship law and the Stolen Generations. It was only natural that the Trevorrow case would attract my interest, though I had little knowledge of the case until hearing and reading about the verdict in the media. After reading the reported judgment, I knew I wanted to write a book about this case. I wanted to bring the Trevorrow case, and with it the story of Bruce Trevorrow, to an audience beyond the legal academy and profession.

Researching and writing this book was a challenge for a number of reasons. One was the fact that I was dealing with a jurisdiction in which I did not reside. Another was that during the process I moved from legal academia to being a parliamentarian, which greatly reduced the time I could devote to the book. I spent nearly ten years working on this project, though never full time. There were many false starts and lengthy punctuations of the work gathering dust. I am pleased that I persevered. I hope you will be, too.

A NOTE ABOUT SOURCES, COURTROOM DIALOGUE AND REFERENCING

I interviewed many people (a list of those interviewed appears in the bibliography), but the South Australian State Solicitor would not approve my request to interview members of the States legal team, although I do not know the reason for this refusal. This was disappointing, but I do not think it has negatively affected the narrative. As well as these interviews, I trawled through court transcripts, court pleadings, affidavits and legal judgments to reconstruct the story of Bruces life and of the trial. I also referred to numerous secondary sources.

With regard to courtroom dialogue, I have taken counsel, witness and judge dialogue directly from the official court transcripts (which may in some cases be gramatically incorrect). In the narrative, I have at times referred to the conduct and thought process of Justice Gray. These references are my hypotheses and suppositions, based on my interpretation of all resources and information available to me. However, I need to make it clear that Justice Gray did not divulge to me his thought process or his views of counsel or witnesses; the same can be said of his staff.

Although I have done extensive research, I have kept referencing notes to a minimum. I have keenly sought not to interfere with the narrative flow of events by repeatedly referencing personal interviews or trial transcripts. For those interested, a glossary of legal terms and an extensive bibliography appear at the end of the book.

PROLOGUE

Bruce, old fella, I cant make you better, but I can give you something to relieve the pain.

The old fellahe is all of fifty-one years oldtries to smile his gratitude. The smile does not make it to his lips.

For the pain or for the hurt? he wants to ask. Its in my heart, he tells the doctor wordlessly, but not that broken-down pump that keeps me alive for no good reason. Its in the other heart. That storehouse of memories that you cant record with your stethoscope, that does not show as squiggly lines on a roll of paper. Thats where the hurt is, and neither you nor I can do a thing about it. It is too late for that. A lifetime too late.

He is not angry with the man who is trying earnestly to help him. He is too young to know about the pain that sears, that screams from the pages of Bringing Them Home, chronicling the hurt, the humiliation, the degradation and the sheer brutality of separating children from their mothers. Too young to know how personal is the suffering caused by the policy that Parliament apologised for just months ago. Too young to know about the price so many paid for this deep assault on our senses and on our most elemental humanity. Too young to know how deeply Bruce hurts.

Next page