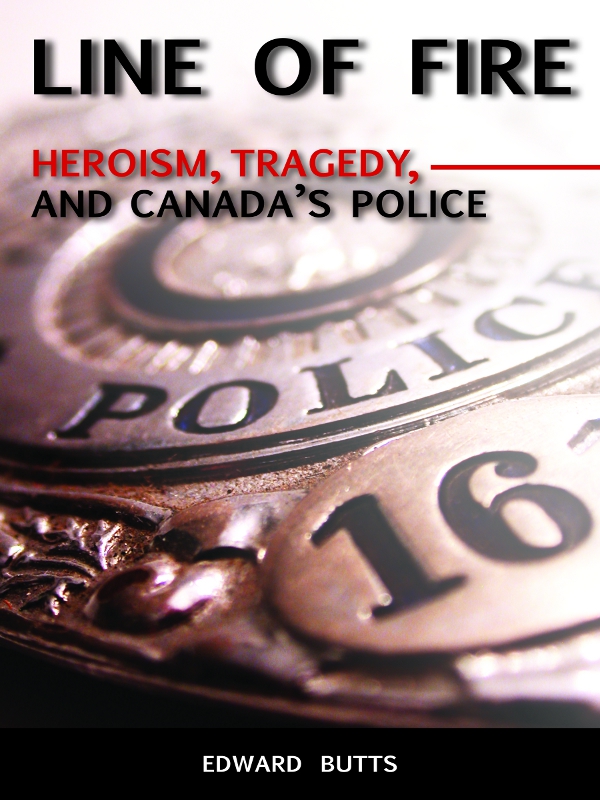

LINE OF FIRE

HEROISM, TRAGEDY,

AND CANADAS POLICE

LINE OF FIRE

HEROISM, TRAGEDY,

AND CANADAS POLICE

EDWARD BUTTS

DUNDURN PRESS

TORONTO

Copyright Edward Butts, 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Project Editor: Michael Carroll

Copy Editor: Cheryl Hawley

Design: Courtney Horner

Printer: Webcom

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Butts, Edward, 1951

Line of fire : heroism, tragedy, and Canadas police / by Edward Butts.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-55488-391-2

1. Police--Canada--History. 2. Police--Violence against--Canada--History. 3. Police--Canada--Biography. I. Title.

HV8157.B88 2009 363.20971 C2009-900306-6

1 2 3 4 5 13 12 11 10 09

We acknowledge the support of The Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and The Association for the Export of Canadian Books, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishers Tax Credit program, and the Ontario Media Development Corporation.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

Printed and bound in Canada. www.dundurn.com

Printed on recycled paper.

Dundurn Press

3 Church Street, Suite 500

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5E 1M2 | Gazelle Book Services Limited

White Cross Mills

High Town, Lancaster, England

LA1 4XS | Dundurn Press

2250 Military Road

Tonawanda, NY

U.S.A. 14150 |

To all those who serve and protect

CONTENTS

F irst, I must thank Kirk Howard, Tony Hawke, and Michael Carroll of Dundurn for thinking of me for this excellent project and entrusting it to me. I am indebted to the following individuals and institutions for assisting me in my search for information and pictures: the Library and Archives Canada; the Provincial Archives of Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Newfoundland, Ontario, and Saskatchewan; the Glenbow Archives; the Moncton, New Brunswick Public Library; the Moncton Museum; the Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library; the Metropolitan Toronto Police Museum; the Victoria Police Department; the Vancouver Police Museum; the British Columbia Law Enforcement Memorial Foundation; the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Fallen Four Memorial Park in Mayerthorpe, Alberta; the London Free Press; the Toronto Star; the Montreal Gazette; and Steve Gibson, Jonathan Sheldan, Colette McKillop, Marie Patterson, Lynette Walton, Chris Mathieson, and Robert Knuckle. Special thanks to Norman Crane of St. Johns, Newfoundland, and, as always, to the staff of the Guelph, Ontario, Public Library.

W e are all familiar with this stock movie scene: the bad guys are committing some sort of crime and the police cars roar in with sirens wailing. The cops jump out of their cars and a dramatic shootout ensues. In the course of the gun battle, one or two police officers go down. By the time the movie is over, weve forgotten about those dead policemen. They were just there for effect, like the exploding cars. They were uniforms without faces. We would never think of them as real people with families at home and lives ahead of them. But thats Hollywood, and its the closest most people get to law enforcement stories.

Ask any group of people what the most dangerous occupation is and you will likely get a variety of replies: police officer, firefighter, high steel worker, miner, and astronaut, to name a few. The people who hold these jobs certainly do place themselves at risk, and they do so knowing that colleagues have died in the performance of those duties. Whether or not one believes the police officer has the most dangerous job, there is no denying that law enforcement is a very hazardous calling. It was dangerous for the nineteenth century North-West Mounted Police constable who rode out alone to track down a fugitive, and it remains so for the twenty-first century urban cop who knocks on an apartment door in response to a domestic dispute call, not knowing what awaits her on the other side of the door. Since 1804, when the first Canadian law enforcement officer known to have perished in the line of duty drowned in a shipwreck on Lake Ontario, hundreds more have lost their lives. Police constables, jail and prison guards, game wardens, and others have gone down in the line of fire.

What is the Line of Fire? That blazing gun battle between cops and robbers in which a police officer is killed might come to mind. Such tragic incidents have, in fact, happened in Canada, but here the term has a much broader definition. The antagonist in a real life police drama might not be an armed and desperate criminal, but the elements, or even a combination of the two. Line of Fire means any potentially deadly situation: a confrontation with an armed criminal, a patrol across frozen Arctic terrain, guard duty in a jail, or a patrol in a small boat on dark waters in the dead of night. The inescapable fact is that a law enforcement officer steps into the line of fire every time he goes on duty, and sometimes the threat doesnt evaporate with the end of the shift.

The accounts presented here come from across Canada. They have been selected from two hundred years of heroism and tragedy in Canadian law enforcement. They tell just a few of the many stories of Canadians who dedicated their lives to the service of the law, and who died in the line of fire.

JOHN FISK:

THE WRECK OF THESPEEDY

I n 1804, the pioneer community of York (Toronto), Upper Canada, was just a small collection of wooden buildings perched at the edge of the howling wilderness, on the shore of Lake Ontario. The site had been chosen as a provincial capital by founder John Graves Simcoe, in part because of the excellent natural harbour that was protected by a long peninsula. Later in the century, a storm would wash away the spit that connected the peninsula to the mainland, creating the Toronto Islands.

Lake Ontario, despite having the smallest surface area of the five Great Lakes, could be a nightmare for mariners in wooden sailing ships. Tricky crosswinds sprang up unexpectedly, and could quickly capsize a vessel. Moreover, at that time the only lighthouse on Lake Ontario (and on the entire Great Lakes system) was the Mississauga Point light at the mouth of the Niagara River. The absence of a guiding light at a strategic spot on the Canadian shore might have been at least partially responsible for the shipwreck that claimed the life of the first Canadian officer of the law known to be killed in the line of duty.

Next page