PETER OWEN LTD

81 Ridge Road, London N8 9NP

Peter Owen books are distributed in the USA by Independent

Publishers Group/Trafalgar Square

814 North Franklin Street, Chicago, IL 60610, USA

Michael Sullivan 2004

This ebook edition 2014

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by

any means without the written permission of the publishers.

PAPERBACK ISBN ISBN 978-0-7206-1040-0

EPUB ISBN 978-0-7206-1730-6

MOBIPOCKET ISBN 978-0-7206-1731-3

PDF ISBN 978-0-7206-1732-0

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library

TO ERIC HEBBORN

persone belle e vive

Inquisitive?

Independent?

Love great writing?

If you have enjoyed this book, visit our website,

where youll find a wealth of top-quality, ground-breaking

and iconoclastic literature and non-fiction

www.peterowen.com

Independent publishers since 1951

Introduction

T HE sonnets and madrigals to Tommaso deCavalieri have never been gathered as a group before. Together they constitute the largest sequence of poems composed by Michelangelo and the first large sequence of poems in any modern tongue in this case the vernacular Florentine that, thanks to Dante, was to become the dominant strain in Italian addressed by one man to another. There are three other subsisiary sequences of his poems; one, directed to the poet and mystic Vittoria Colonna, of about forty poems; a second, largely quatrains, consisting of epitaphs for the fif-teen-year-old Cecchino Bracci produced at the insistence of Luigi del Ricchio, a literary collaborator of Michelangelo and uncle to the boy; and a third, the poems now considered a literary exercise, to la donna bella e crudele.

Michelangelo had begun composing poetry some time before he was thirty in a desultory fashion, and little in his early production suggests that he would turn into the greatest lyric poet of his generation. What brought about the change was his meeting and love for Cavalieri. The intensity and complexity of feeling in their relationship brought out corresponding capacities to shape and deepen paradoxes of commitment, contradictory yearnings and opposing pressures that lasted into Michelangelos old age. The period of their high exercise runs from 1532 to around 1548, the year after the death of Vittoria Colonna. From then on inspiration and production dwindled, though there are still some poems that encapsulate the power and skill that burst upon Michelangelo with his love for Cavalieri. It is the centrality of the experience that makes me describe the other sequences as subsisiary, not any marked difference in formal skill or the Bracci epitaphs apart thematic interest. So unified was the impulse that dating and attribution of various poems to one cycle or the other has shifted backwards and forwards from editor to editor and translation to translation. This is less the result of Michelangelos own shifts in the gender of possessives in his drafts, of his addressing Vittoria Colonna as signore, lord, or of the meddling appeasement practised in the first published edition by Michelangelos great-nephew in his accommodation to the more perturbable society of 1623 but, rather, of a tautness of mind and pitch of feeling common to them all and occasioned by the inescapable beauty of Cavalieri.

Tommaso deCavalieri was born in Rome to Emiliano deCavalieri and a daughter of the Florentine banker Tommaso Bacelli. In the autumn or winter of 1532, when he was twenty-one or twenty-two, he was introduced to Michelangelo, then fifty-seven years old. The renowned sculptor, painter, architect agreed to do something he never had before done and was never to repeat again: he consented to give drawing lessons to his new friend. Later he was to do a drawing of Cavalieri, a full-length cartoon, something, as Vasari tells us, he refused to before and after because he abhorred drawing from life unless it was of infinite beauty. Cavalieris appearance at this time, his intellectual and moral gifts, were testified to in a public lecture given in Florence by Benedetto Varchi on Michelangelos poetry, in particular on G. 98 and its mention of an armed cavalier: ... addressed to Tommaso Cavalieri, a most noble young Roman, in whom I recognised in Rome (apart from the incomparable beauty of his body) so much comeliness of behaviour, and such excellent wit and gracious manner, that he well deserved, and deserves still, to be the more loved by those who come to know him better.

The first of Cavalieris three letters to Michelangelo, dated 1 January 1533, speaks of his own artistic production, because of which you showed me no little affection. Michelangelos letters, in return, speak a great love. Donato Giannotti reports in his Dialogi (1546), a transcription of discussions on Dante held by Giannotti, Michelangelo, del Riccio and others, that Michelangelo declared himself of all men the most inclined to love persons, immediately adding that when he meets someone of great merit I am forced to fall in love with him. The shift from the feminine plural of persone to the masculine singular, of particular help in the interpretation of the final line of sonnet G. 79, has large significance for the whole of Michelangelos life. Whatever the full nature of the relationship with the man whom he described as light of our age, unique in the world, the friendship that followed was tenacious and enduring.

We know nothing of any sexual act of Michelangelos, with man or woman, or even whether he engaged in any such. What evidence the love sonnets provide a mention on loving arms in G. 72 and the perverse imagery of G. 94 is set in an optative, wishful tense, while the tenebrous guilt for great sin of later poems remains generic. Whether, as Michelangelo claimed, his love for Cavalieri was chaste, their contemporaries thought otherwise, and the relationship caused much gossip and speculation. It was certainly, in an ample sense, erotic.

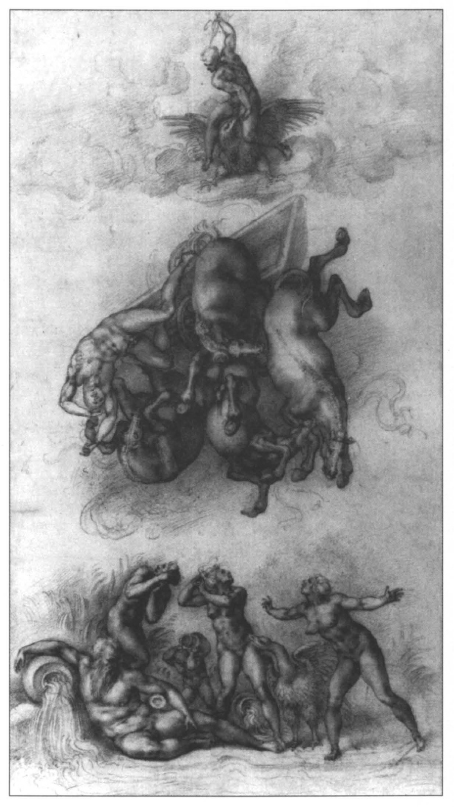

It began, as I have said, with drawing lessons. Cavalieri as pupil had sufficient talent to justify Michelangelos enthusiasm and produced many drawings, most of them in 15334 at the time of the lessons. If they are now slighted it is not so much for their markedly non-professional execution as for the fact that they were earlier attributed to Michelangelo himself. This odd switching of their production was to happen again. Cavalieris drawings, in fact, differ from Michelangelos in their original style of composition and their psychological realism As we shall see, Michelangelo made considerable use of Cavalieris capacities. The method of the lessons, it appears, was for Cavalieri to suggest a topic, make a drawing, and for Michelangelo, rather than correct it, to reply with a drawing on the same subject, which he then gave to Cavalieri. His gift of pictures to Cavalieri is mentioned in sonnet G. 79.

These drawings, and others inherited from Sebastiano del Piombo, formed the basis of a collection that became famous in Cavalieris lifetime. After his death the collection was bought by Alessandro Farnese for the remarkable sum of 500 scudi and most of it is now in Windsor Castle. Tityus, The Fall of Phaeton and Ganymede (now thought of as lost Windsor has a copy by Giulio Clovio) were among those given directly to Cavalieri. Ludvig Goldscheider describes Tityus as Michelangelos most erotic drawing after Leda and the Swan . The poor state of some of the drawings is the result of Cavalieris generosity in lending them to copyists.