Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

TO MY MOTHER, CHERI KAMEN TARGOFF

H IGH IN THE HILLS thirty miles to the east of Rome is the ancient town of Subiaco. Named for the artificial lakes that the emperor Nero created from the upper course of the Aniene River in order to build himself a sumptuous villathe towns Latin name, Sublaqueum, literally means under the lakesSubiaco was where Saint Benedict spent three years as a hermit in a cave before founding his first monastic community on the site in the early sixth century. Looking as if it had been carved directly into the cliffs, the monastery of San Benedetto lies at the top of a very long, treacherously narrow drive lined with beautiful woods. There are sweeping views of a verdant valley and gentle mountains in the distance.

Just down the hill from the Benedictine monastery on the same winding road is a second monastery, dedicated to Benedicts sister, Saint Scholastica. This was one of the twelve monasteries that Benedict founded in the area before leaving for the town of Cassino to the south. Here he finalized the Benedictine Rule, which laid out the exemplary asceticism that became the standard for the Western monastic tradition. Although less dramatic in its setting, the abbey of Saint Scholastica boasts three magnificent cloisters, the oldest of which dates back to the twelfth century. The monastery was renowned in the Middle Ages for its library, which had a famous scriptoriuma separate room where monks copied manuscriptsand it held ten thousand volumes by the year 1300. It was in the library of Saint Scholastica that Italy entered the world of print: in 1464, two German clerics, Arnold Pannartz and Konrad Sweynheym, crossed the Alps to set up a printing press in Subiaco, where they began to produce books using a technology that soon made the scriptorium obsolete.

It was also in this celebrated librarynow located in a different part of the monasterythat I found myself on a sweltering summer day several years ago, facing a Benedictine monk who was handing me a file of precious letters and documents from the early 1500s. I had come to consult the archive of the Colonna family, which has been housed in Subiaco since 1996, when it was moved from Rome. The Colonna archive has almost a hundred thousand items dating from as early as the twelfth century, and the great majority of the holdings are personal letters. From the late Middle Ages through the early twentieth century, the Colonna ruled over much of the territory to the southeast of Rome in the area known as the Castelli Romani, dotted with the castles of the great Roman families. Within Rome, the family ownedand still owns todaya grand palace in the very heart of the city; its magnificent art gallery and selected apartments are open to the public on Saturday mornings.

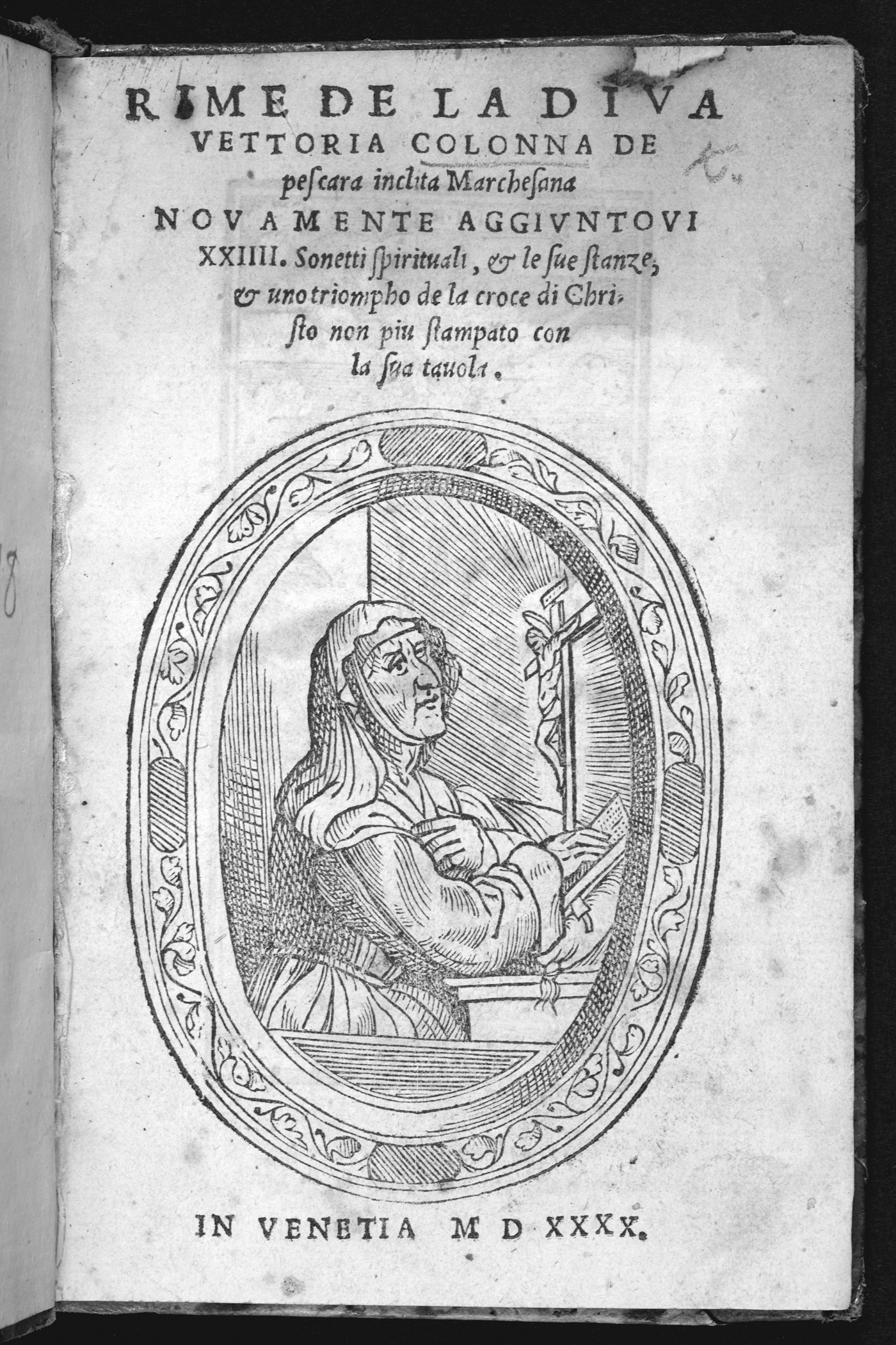

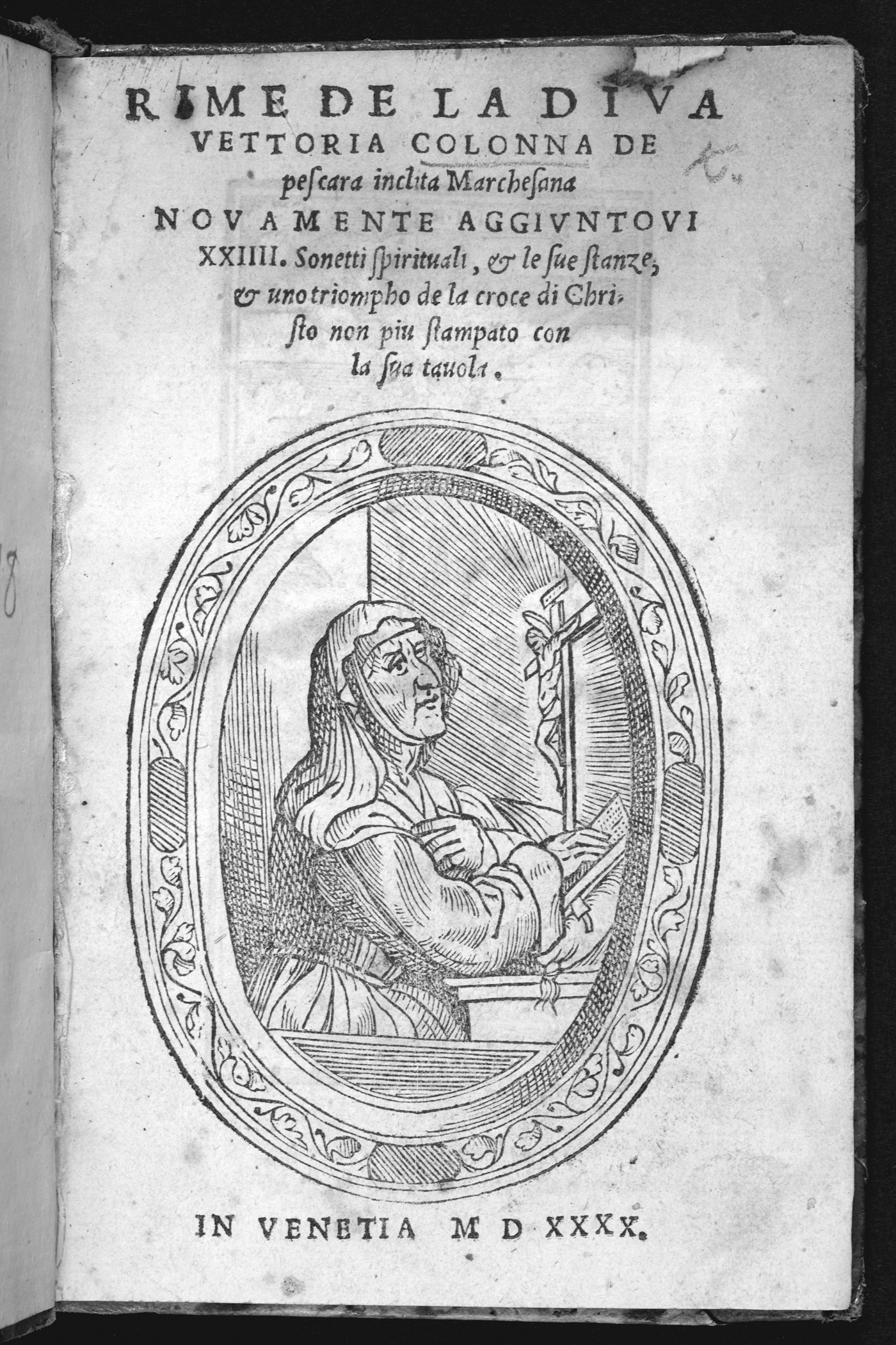

My interest was in the poetry of one member of the family, Vittoria Colonna, who lived from 1490 to 1547. Among her many accomplishments, Vittoria was the very first woman in all of Italy to have a book of her poems appear in print. I had discovered her work while writing a book on Renaissance love poetry, and had been struck by the hundred or so sonnets that she addressed to her husband after his death. Given their emotional power and complexity, I was surprised to learn that she had subsequently abandoned love poetry altogether, and chosen to write only spiritual verse. In the sixteenth-century Italian books of her poetry that I had read at Harvards Houghton Librarythere are no complete translations of her poems available in English, and the only Italian edition, published in 1982, is out of printI noticed that in the illustration on the title page of one edition she looked very much like a nun. I also noticed she was consistently called divine. All of this intrigued me, and when I was in Rome some months later and learned that many of Vittorias original letters were in a nearby archive, I decided to make the trip.

Title page of 1540 edition of Vittoria Colonnas Rime (Venice: Zoppino) ( The British Library Board, May 9, 2017, General Reference Collection DRT Digital Store 11426.aa.18)

There is no published or digital catalog of the Colonna archive, so I did not know exactly what I was looking for. But there was a rather primitive database on the librarys computer, and I was able to do a search for Vittoria. Two different call numbers came up, which I jotted down on a slip of scrap paper. The monk who had showed me into the room promptly copied the two numbers onto the palm of his handI offered to give him my piece of paper, but he said he preferred his methodand he disappeared into the archive. Some fifteen minutes later, he returned with two filesone a very thick set of documents, the other a single, large manuscriptwhich he placed on the table in front of me.

What I found in those files gave me my first glimpse of the extraordinary life Vittoria had led. I read her scribbled notes to her brother Ascanio about his fight with Pope Paul III over taxes on salt, and to her nephew Fabrizio about Ascanios difficulties with the princess of Sulmona. I pored over her letter to the padre generale of the Capuchin monks urging him to treat the friars well and not serve them a low-quality bread, given how little they ate, and her response to the constables of the Colonna fief of Monte San Giovanni instructing them not to comply with the new system of taxation that the papal commissioner was trying to introduce. I found three pages from her personal account book, listing payments made and monies received for 1543 and 1544. I studied the inventory that her executor drew up the day after her death in 1547, listing the items left behind in her rooms at the nunnery in Rome where she had been livingI was particularly struck by the poignant mention of a single gold spoon. I read an irate letter from the same executor to her brother announcing his horror about the disposition of her wealth.

After I went through the quite substantial stack of letterscarefully taking photographs, with the monks permission, so that I could study them con calma , as the Italians say, later onI closed up the file and turned to the bound manuscript. Inside this rather grandiose volume filled with miscellaneous legal materials related to the Colonna family was the most elegant document I had seen so far: the wedding contract between Vittoria and her husband, Ferdinando Francesco I dAvalos, Marquis of Pescara. (A marquis, or marchese , was the ruler of lands on the marche , the outskirts of territory controlled by the issuing authority, in this case the kingdom of Naples.) The contract was drawn up in Naples on June 13, 1507, when Vittoria and Ferrante (as Ferdinando was known) were both around seventeen years old. Written in a very beautiful hand, it was nearly twenty pages long, and specified, alternately in Latin and Italian, the terms of the dowry. There were many more details than I could possibly take in, and my Latin was very rusty, but I understood that the enormous sum of fourteen thousand ducatstwelve thousand in cash, and the remaining two thousand in portable propertywas to be transferred to Ferrante from Vittorias father, the great military captain Fabrizio Colonna, whom I knew only as the principal speaker in Niccol Machiavellis The Art of War .