28.

Prologue

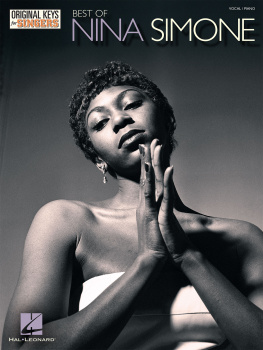

I understood fully for the first time the importance of black song, black music, black arts. I was handed my spiritual assignment that night.

OSSIE DAVIS , after seeing Marian Anderson at the Lincoln Memorial, Easter Sunday, 1939

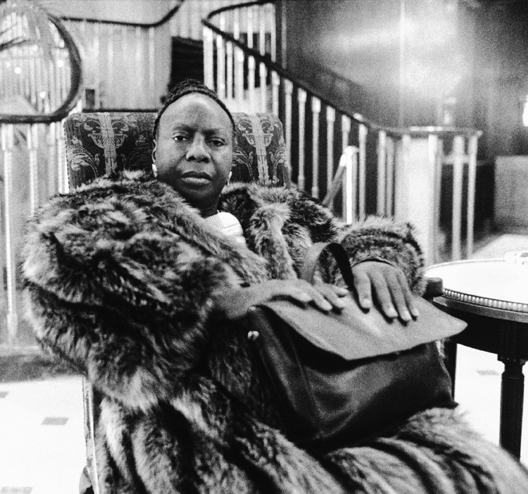

I t was more a path emerging than a promise fulfilled that put Nina Simone on a makeshift stage in Montgomery, Alabama, on a sodden March night in 1965. She wanted to sing for the bedraggled men and women who had trekked three days from Selma to present their case for black voting rights to a recalcitrant Governor George Wallace. Nina was following the lead of James Baldwin, her good friend, mentor, and sparring partner at dinner-table debates, a role he shared with Langston Hughes and Lorraine Hansberry. They were her circle of inspiration, writers who found their voice in the crackling word on the pagethe deft phrase and the trenchant insight that described a world black Americans so often experienced as unforgiving.

Nina linked her voice to theirs, understanding from the time she was Eunice Waymon, a precocious little girl in Tryon, North Carolina, what it was to be young, gifted, and black, even if she couldnt find the words to express it. On that stage in Montgomery, long since transformed into Nina Simone, she sang Mississippi Goddam, her litany of racial injustice and a signal that she, too, had found her spiritual assignment: to use her talent for the singular cause of freeing her people and not incidentally herself. She never suggested the task was easy, and anyone willing to listen, willing to heed her exhortations, could engage in the struggle at her side.

I didnt get interested in music, Nina explained. It was a gift from God. But when private demons besieged her, a rage of breathtaking dimension obscured that gift, blinding her to everyday realities even as the anger informed her creations and at the same time served to attract, provoke, and on occasion repel an audience. Yet through it all came the unmistakable pride of accomplishment. When Im on that stage, I assume honor. I assume compensation, she declared, and I should.

In the best of times Nina could embrace the mysteries of her art, finding comfort in the ineffable. Did you know that the human voice is the only pure instrument? she wrote one of her brothers. That it has notes no other instrument has? Its like being between the keys of a piano. The notes are there, you can sing them, but they cant be found on any instrument. Thats like me. I live in between this. I live in both worlds, the black and white world. I am Nina Simone, the star, and I am not here. Im a woman. My secret self is between these worlds.

1. Called For and Delivered

~ June 1898-February 1933 ~

T he gifts that would turn Eunice Waymon into Nina Simone were apparent by the time she was three, though the passions, the mood swings, and the ferocious intensity that marked her adult life were buried for years under her talent. She was born on February 21, 1933, the sixth of eight children, in Tryon, North Carolina, a town perched at the border between North and South Carolina, on the southern slope of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The beautiful surroundings, the pleasant climate, and the good railroad service established by the turn of the century helped Tryon grow from a rural outpost to a haven for white artists and their friends, many of them from the North. Visitors stayed and put down roots, those with keen business instincts making investments that gave the town its municipal backbone.

Eunices birth certificate listed her father, John Davan Waymon, as a barber and her mother, Kate Waymon, as a housekeeper. But these descriptions, necessitated by the limited space on the states official form, failed to capture the creative, entrepreneurial path John had woven through a world both circumscribed and defined by race. Likewise, housekeeper did not do justice to the pursuits of his equally determined wife to stretch the boundaries of their lives and give the family its spiritual core.

They were respected members of black Tryon and were treated with the patronizing courtesy whites traditionally reserved for those black residents deemed a cut above. The Waymons set an example of hard work for their children, underscored by a deep faith that from Kates perspective could ease disappointment and loss. Eunice had her doubts, and in her troubled moments as an adult, she would take little solace from her mothers lessons. Her fathers buoyant spirit and pragmatic outlook, on the other hand, drew her in. He was a clever man, she recalled. Although he wasnt educated, he had a genius for getting on.

John Davan Waymon and Kate Waymon came from South Carolina, each the descendant of slaves. John, born June 24, 1898, in Pendleton, a small town near Clemson University, was the youngest of several children. A gifted musician, he played the harmonica, banjo, guitar, and Jews harp. He could take a tub and make music out of it, one of his children would say later with evident admiration, noting, too, that his father had the unique ability to whistle two notes at once. We could hear that many blocks awayDaddy whistling in the night. Tall, with a high forehead and prominent cheekbones, he looked the part of the song-and-dance man he became in his teens, dressed in a sharp white suit, spats over his shoes, cane in hand when he entertained the locals.

Kate was born November 20, 1901, and christened Mary Kate Irvin (though some family members spelled it Ervin), the baby among fourteen childrenseven girls and seven boys. She was never sure what town her parents lived in when she arrived, only that it was in South Carolina, probably Spartanburg County. Her father was a Methodist minister, and while her mother was not officially trained, she had absorbed enough religion to carry on the ministry if Reverend Irvin was called away. Kates heritage on her mothers side was an unusual mix. She took after her maternal grandfather, who was a full-blooded Indian, tall and of the yellow kind, as she recalled, and her maternal grandmother, who was short and dark with luxuriant black hair, which Kate inherited. She often wore it in a braid wrapped around her head.

One of Kates sisters, Eliza, was married to a pastor who led the congregation in Pendleton where John Davan worshipped. Sometime in 1918 he introduced John, then twenty-one, to Kate, only seventeen. Kate remembered that they sang Day Is Dying in the West together at church. John was smitten, and he promptly wrote Kate asking to visit her in Inman, where she now lived with her widowed mother. On that first visit they went for a buggy ride, and soon John was coming by every Saturday and staying through Sunday evening. Their routine on these visits usually included a ride in the countryside, the couple entertaining themselves with duets. Kates alto blended easily with Johns tenor on their favorites, Whispering Hope and Sail On. At the Irvins they sang around the little organ Mrs. Irvin had bought for her daughter. She paid for a few lessons, and then Kate taught herself the rest.