Table of Contents

FOR CHARLES WALTON, WHO SHOWED ME THE WAY

PROLOGUE

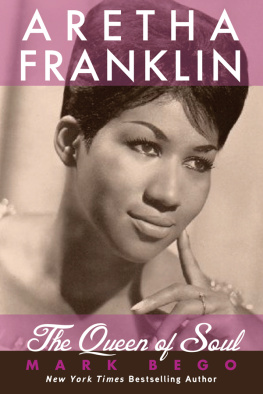

George Gershwin wouldnt know his own song when Im through withit. I cant stay hidebound to any melody.

DINAH WASHINGTON

It was a Saturday night in February 1961 on Chicagos South Side. The patrons at Roberts Show Lounge were in a festive mood the men in sharp business suits, the women dressed somewhere between Sunday church and New Years Eve. A few whites were scattered among the tables; the rest were black Chicagoans waiting expectantly for the show to begin even though most of them had seen the star attraction many times.

That didnt matter. When Dinah Washington was in town, the music was always good and always different. No one knew when something unusual might happen. What would she sing? What would she wear? What was new in the offstage life that raised eyebrows and made headlines?

Dinah had just married her sixth husband, a slight, handsome actor twelve years her junior. But it was a good bet shed have a story about the good-looking man whod caught her eye the other day. She might tell a few jokes, too. And if the patrons were noisy when she sang, Dinahs sharp tongue would silence them. It was grand to watch as a spectator, though less inviting to be on the other end of her momentary annoyance.

Shortly after ten the announcer came over the loudspeaker: Ladies and gentlemen, Miss DDinah Washington.

She walked to the microphone with a slow, confident gait, sizing up this nights audience as they took her in from their seats. She was just over five feet but seemed much taller. It wasnt the high-heeled dress shoes but her command of the space and the moment. She turned to the band and signaled the key. The piano player hit the opening notes. The bass and drums came in a split second later, and Dinah was off. She opened upbeat, then sang some ballads, finally some blues, first the bawdy tunes and then the ones that made her cry with those lines about love gone sour and life all alone.

At the end the audience, on their feet, cheered for more.

Dinah treasured those moments, hard earned and savored in the early morning hours when the applause had faded. They were the culmination of the silent, even furtive dreams of the young girl born Ruth Jones far away from the glory of center stage and the fans who would one day call her Queen.

Tuscaloosa

19001928

Tuscaloosa lies at the heart of Alabamas natural riches. In the 1920s, iron ore, a key ingredient for making steel, was plentiful. So was limestone. The hills and valleys were full of hard and soft timber for mill and factory. Rail service was more than adequate, and because the city was built on the banks of the Black Warriorthe literal translation of Tuscaloosa, the Choctaw name of a tribal chiefmanufactured products could be shipped south to the port city of Mobile and on to faraway markets.

Between 1890 and 1923 the citys population had more than tripled, to 18,500 at last count. With outlying communities included the population was close to 30,000. The latest chamber of commerce brochure, a mixture of pride and boosterism, listed ninety-nine reasons why new business should come to this growing and prosperous southern city. Forty-seven new firms had opened in the previous year; five miles of new streets had been paved; an eleven-story office building had been completed and occupied by a bank. Thirty acres had been added to the golf course; Tuscaloosa ranked fourth in Alabama in the number of automobiles within its city limits.

The newest city directory gushed over Tuscaloosas many beautiful homes and her broad streets and avenues which are arched with giant shade trees. It has long been known as a city of culture and refinement. The University of Alabama, the seat of education for the state, was in the center of town, and the estimable William Jennings Bryan had recently spoken on campus.

Accurate as they were, these descriptions were only a partial portrait. Nearly half of Tuscaloosa was black. Older residents had been slaves; most others were the children and grandchildren of slaves. None lived in the Tuscaloosa of big homes, broad streets, and culture and refinement, and although they kept those big homes clean and their occupants well fed and cared for, they were absent from the citys civic life. The chamber of commerce made no reference to black Tuscaloosa in its publicity brochure, but by indirection the city directory provided a glimpse of their world: blacks and black-operated businesses were identified by an asterisk before their names. The street-by-street listings of residents and shops, asterisks in place, showed most living in two places: the west-southwest part of town not far from the railroad tracks, an area known as Shack-town, and the small town of Northport just over the Black Warrior River. The occupations listed after the asterisked names testified to the circumscribed opportunities in black Tuscaloosa: chauffeur, cook, engine cleaner, gardener, laborer, laundress, porter, though there were also a half-dozen barbers who had their own shops and a few residents who taught at the all-black schools. Both male and female white help may be had in any number wanted, and such colored labor as may be needed in the boiler room and like places may be had, said one brochure that served both as recruitment tool and a guide to local custom.

The number of black churches was strikingseventeen. Half were Baptist, but whatever the denomination, they reflected the central truth that the church was a place of community and comfort in an otherwise difficult world, a place to find joy and release, strength and renewal. Decades later, a book on the history of the oldest black church in Tuscaloosa, Hunters Chapel AME Zion founded in 1866, was appropriately titled How Firm a Foundation.

Rufus and Matilda Williams were more fortunate than many of the families in the black community. Though they lived in the outlying hamlet of Sylvan, some twenty miles south of the city limits, they had moved closer in after their daughter, Asalea, was born September 23, 1905. They owned a small farm, which freed them from the constant indebtedness of sharecropping, but like the tenant farmers, they, too, worried about good soil, good weather, and a good yield. In a county where nearly half of the black population and a quarter of the white residents were illiterate, the Williamses could read and write. They were intent on making sure their daughter could, too, and sent her to St. Pauls Lutheran, one of the all-black schools. Perhaps a reversal of fortune required Asalea to stop her formal schooling after she finished eighth grade at St. Pauls. She did not attend high school, and that most likely accounted for an appreciation of education that would last her entire life.

Though Rufus and Matilda were twenty-one and twenty when they got married, Rufus nonetheless teased Asalea when she turned seventeen because she hadnt yet found a husband. But by the time she was nineteen she had met Ollie Jones, the handsome, rakish son of Ike and Mattie Jones, who lived nearby in Northport. Ollie, who was fourteen months older than Asalea, was one of six children five boys, one girl. Ike was a tenant farmer; Mattie took care of the children. Neither could read or write. The boysChapp, Richard, Albert, known as Snow, Ollie, and Williewere charmers. Years later their children would admit that all the Jones meneven their grandfather Ikewere womanizers.

Next page