Angus Campbell (19392015) was a linguist, translator and scholar. After a long career as an international advertising executive, he retired to Sicily where he was resident for many years. He was an expert in the political, diplomatic, social and cultural history of eighteenth-century Sicily and his interest in Domenico Caracciolo was borne out of that research.

This is the first work in English to be devoted to an important figure in the history of Enlightenment Europe. Caracciolo is brought alive through his colourful correspondence, only available before in Italian.

William Doyle,

Emeritus Professor of History,

University of Bristol

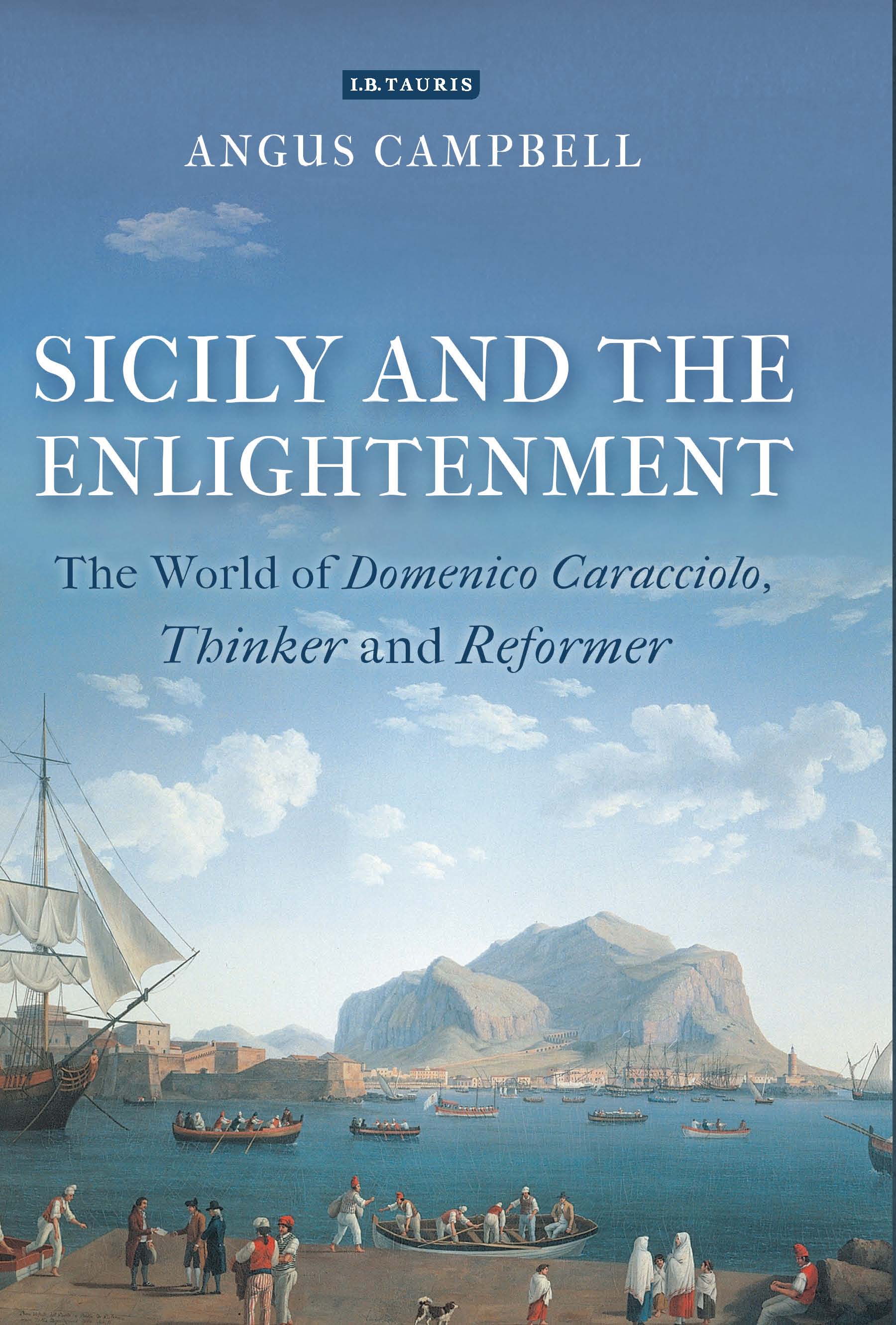

Portrait of Domenico Caracciolo, courtesy of the Fondazione Federico Secondo, Palermo.

Sicily and the Enlightenment

The World of Domenico Caracciolo,

Thinker and Reformer

Angus Campbell

Published in 2016 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2016 the Estate of Angus Campbell

The right of Angus Campbell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the Estate of Angus Campbell in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

ISBN: 978 1 78453 575 9

eISBN: 978 0 85772 899 9

ePDF:978 0 85772 802 9

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Typeset by Saxon Graphics Ltd, Derby

Contents

Angus Campbell (19392015) was a linguist, translator and scholar. After studying medieval history at Magdalen College, Oxford, he spent several years in the small town of Oristano in Sardinia teaching English. He then returned to London and embarked on a career in advertising. In 1969 he married Caterina Mollica, a Sicilian, and they moved to Rome where he continued in advertising, eventually setting up his own company. There they lived in a rented flat near the Spanish Steps, with the famous Caff Greco behind them and the equally famous restaurant Ranieri opposite their front door and the rooftop flag of the Knights of Malta fluttering right in front of their balcony. From there they moved to their own flat nearby in the Via Vittoria, where their rooftop terrace overlooked the gardens of the Greek Convent.

The Mollicas are a large and distinguished Sicilian family and, after retiring at the beginning of the new millennium, the Campbell-Mollicas moved from Rome to the family compound near Calatafimi in western Sicily. From there the great tourist site of Segesta is visible a few kilometres away and a swim in its hot thermal pool became part of Campbells daily routine. They lived first in a small cottage and later in the big house nearby, which they had converted from the ruins of an old farmhouse. In Calatafimi, as in Rome, they played host to a stream of friends and every autumn to the olive pickers who would come from all over the world to pick their olives in exchange for board and lodging.

Their life there elicited from Campbell his first book, Calatafimi: Behind the Stone Walls of a Sicilian Town (2008), a book full of the humorous details of local life interspersed with bursts of history, and overall a loving tribute to his wifes family. In his last years, Campbell managed to complete his final book on the much more familiar subject of Samuel Butler and his links with Sicily. He was stoical in pain, finally succumbing to cancer on 2 November 2015. His widow has laid his ashes to rest in their beautiful garden where she, their children and grandchildren can continue to keep him abreast of all the local gossip.

Fred Atapour, September 2016

D omenico Caracciolo was born in Spain in 1715. His father, Tommaso Caracciolo, Marchese di Villamaina e Capriglia and of an old noble Neapolitan family, was serving in His Catholic Majestys Army; his mother, D. Maria de Alcantara Porras y Silva, was Spanish.

Very little is known of Domenicos early life. He and his family returned to Naples, where he received his education and his formation as a young man, when he was still a child. After an unsatisfying career as a magistrate, he left the city at the age of 37, returning at the age of 71 as prime minister. The intervening years were taken up with diplomatic posts in Turin, London and Paris, and, most significantly, as viceroy in Sicily from 1781 to 1786, where he battled to impose rational reforms on what was then the backward feudal corner of Enlightened Europe.

That he was a younger son marked Domenicos life in various ways. In the first place, it meant that, though he would never be forbidden from marrying, he would be unlikely to make a brilliant match efforts in that matter would be reserved for his elder brother. He resolved his own sentimental life in a most rational eighteenth-century way by picking and choosing discreetly, often among ladies of the theatre, as he went through life. When asked once by Louis XV about his love life, he replied to His Majesty that he bought it ready made, though usually his references to lady friends in letters were far less revealing. What this means to a biographer, however, is that he did not have a stable home in the normal sense of the word. There was no wife and children, no in-laws, no family estate, all of which engender documents, arguments and stories, and therefore Caracciolos private life is more difficult to track.

Not being the eldest son also meant that he did not inherit. Although his family was old and noble, it was not at this time affluent, and Domenico (Mimmo to his friends) had found that some form of a career was expedient. In his station of life there were only three possibilities: the army, the church or the law. The latter two offered eventual outlets into diplomacy and politics. As we shall see, his own education, as well, probably, as popular anticlerical feeling in Naples at the time, were to exclude the church as a possibility. But this is to jump ahead in time. What needs to be emphasised is that his being single and becoming a man of office means that we have to unravel his life by means of official letters, decrees and hearsay.

Despite energetic efforts by eminent Neapolitan historians, very little is known about Caracciolos early life in Naples. Benedetto Croce has a delightful picture, which might well be true, of Domenico and other young members of his family being taught in a sort of extended-family college, and goes on to say that he studied music, poetry and mathematics, presumably at the same school, but no hard evidence is offered. In later years, however, Caracciolo fought bravely in Paris in favour of the Italian musician Piccinni against the court-favoured Gluck, tried hard to inveigle the French mathematician Le Grange to teach at the University of Palermo, showed energetic interest in all forms of literature (which involved him in bookish activities that ranged from being intimately concerned with the consequences of Alfieris duel in London to promoting Arabic studies in Sicily), and was also involved in the importation of foreign books that, for reasons of censure, were not to be had in the kingdom. It is fair to assume, then, that his schooling was soundly based wherever and however it was carried out.