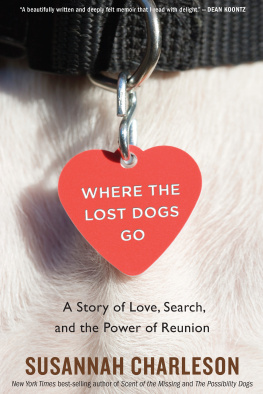

Copyright 2010 by Susannah Charleson

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Charleson, Susannah.

Scent of the missing : love and partnership with a

search-and-rescue dog / Susannah Charleson.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-547-15244-8

1. Rescue dogsTexasDallasAnecdotes. 2. Search dogsTexasDallasAnecdotes. 3. Search-and-rescue operationsTexasDallasAnecdotes. 4. Golden retrieverTexasDallasAnecdotes. I. Title.

SF 428.55. C 43 2010

636.7'0886dc22 2009033783

e ISBN 978-0-547-48850-9

v3.0114

PHOTO CREDITS: All photographs by Susannah Charleson except as follows: Skip Fernandez and Aspen: Dallas Morning News/Louis DeLuca. Fleta and Saber: Mark-9 Search and Rescue. Max and Hunter: Mark-9 Search and Rescue. Jerry and Shadow: Mark-9 Search and Rescue. Maxand Mercy: Kurt Seevers/Mark-9 Search and Rescue. Focsle Jack: Devon Thomas Treadwell. Confidence on a rappel line: Sara Maryfield/Mark-9 Search and Rescue. Certified Puzzle: Daniel Daugherty.

For Ellen Sanchez, who always believed, and

brought a thousand cups of tea to prove it.

For Puzzle. Good dog. Find more.

AUTHORS NOTE

Scent of the Missing is a memoir of my experiences as a field assistant and young search-and-rescue canine handler. Unless otherwise attributed, the perspectives and opinions expressed here are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of teammates and colleagues in the field.

Though this book is a nonfiction account of working search-and-rescue, compassion for the affected families and respect for their privacy have directed me to change names, locations, and identifying circumstances surrounding the searches related here. Who, where, and when are frankly altered; what, why, and how are as straightforward as one persons perspective can make them.

The dogs are all real. You can hold up a biscuit and call them by name.

1. GONE

I N THE LONG LIGHT of early morning, Hunter circles what remains of a burned house, his nose low and brow furrowed. The nights thick air has begun to lift, and the German Shepherds movement catches the emerging sun. He is a shining thing against the black of scorched brick, burned timber, and a nearby tree charred leafless. Hunter inspects the tree: half-fallen, tilting south away from where the fire was, its birds long gone. Quiet here. I can hear his footpads in the wizened grass, the occasional scrape of his nails across debris. The dog moves along the rubble in his characteristic half-crouch, intense and communicative, while his handler, Max, watches.

Hunter rounds the house twice, crosses cautiously through a clear space in the burned pile, and returns to Max with a huff of finality. Nothing, he seems to say. Hunter is not young. There are little flecks of gray about his dark eyes and muzzle, and his body has begun to fail his willing heart, but he knows his job, and he is a proud boy doing it. He leans into his handler and huffs again. Max rubs his ears and turns away.

Shes not in the house, I murmur into the radio, where a colleague and a sheriffs deputy wait for word from us.

Lets go, says Max to Hunter.

We move on, our tracks dark across the ash, Hunter leading us forward into a field that lies behind the house. Here we have to work a little harder across the uneven terrain. Max, a career firefighter used to unstable spaces, manages the unseen critter holes and slick grass better than I do. Hunter cleaves an easy path. Our passage disturbs the field mice, which move in such a body the ground itself appears to shiver.

Wide sweeps across the field, back and forth across the wind, Hunter and Max and I (the assistant in trail) continuing to search for some sign of the missing girl. Hunter is an experienced search dog with years of disaster work and many single-victim searches behind him. He moves confidently but not heedlessly, and at the base of a low ridge crowned by a stand of trees, he pauses, head up a long moment, mouth open. His panting stops.

Max stops, watches. I stand where I last stepped.

And then Hunter is off, scrambling up the ridge with us behind him, crashing through the trees. We hear a surprised shout, and scuffling, and when we get to where he is, we see two men stumble away from the dog. One is yelping a little, has barked his shin on a battered dinette chair hes tripped over. The other hauls him forward by the elbow, and they disappear into the surrounding brush.

A third man has more difficulty. He is elderly and not as fast. He has been lying on a bare set of box springs set flat beneath the canopy of trees, and when he rises the worn cloth of his trousers catches on the coils. We hear rending fabric as he jerks free. He runs in a different direction from the other twonot their companion, I thinkand a few yards away he stops and turns to peek through the scrub at us, as though aware the dog is not fierce and we arent in pursuit.

Our search has disturbed a small tent city, and as we work our way through the reclaimed box springs and three-legged coffee tables and mouse-eaten recliners that have become a sort of home for its inhabitants, the third man watches our progress from the edge of the brush. This is a well-lived space, but there is nothing of the missing girl here. Charged on this search to find any human scent in the area, living or dead, Hunter has done what he is supposed to do. But he watches our response. From where I stand, it is clear Hunter knows what weve found is not what we seek, and that what we seek isnt here. He gazes at Max, reading him, his eyebrows working, stands poised for the Find more command.

Sector clear, I say into the radio after a signal from Max. I mention the tent city and its inhabitants and learn it is not a surprise.

Good boy, says Max. Hunters stance relaxes.

As we move away, the third man gains confidence. He steps a little forward, watching Hunter go. He is barefoot and shirtless. Dog, dog, dog, he says voicelessly, as though he shapes the word but cannot make the sound of it. Dog, he rasps again, and smiles wide, and claps his hands.

Saturday night in a strange town five hundred miles from home. I am sitting in a bar clearly tacked on to our motel as an afterthought. The clientele here are jammed against one another in the gloom, all elbows and ball caps bent down to their drinksmore tired than social. At the nearby pool table, a man makes his shot, trash talks his opponent, and turns to order another beer without having to take more than four steps to get it. This looks like standard procedure. The empty bottles stack up on a nearby shelf that droops from screws half pulled out of the wall. Two men dominate the table while others watch. The shots get a little wild, the trash talk sloppier.

A half-hour ago, when I walked in with a handful of teammates, every head in the bar briefly turned to regard us, then turned away in perfect synchronization, their eyes meeting and their heads bobbing a nod. We are strangers and out of uniform, but they know who we are and why we are here, and besides, theyve seen a lot of strangers lately. Now, at the end of the second week of search for a missing local girl, they leave us alone. We find a table, plop down without discussion, and a waitress comes out to take our orders. She calls several of us honey and presses a hand to the shoulder of one of us as she turns away.

Either the town hasnt passed a smoking ordinance, or here at the city limits this place has conveniently ignored the law. We sit beneath a stratus layer of cigarette smoke that curls above us like an atmosphere of drowsy snakes, tinged blue and red and green by the neon signs over the bar. Beside the door, I see a flyer for the missing girl. Her face hovers beneath the smoke. She appears uneasy even in this photograph taken years ago, her smile tentative and her blond, feathered bangs sprayed close as a helmet, her dark eyes tight at the edges, like this picture was something to be survived.

Next page