Fearless and prepared to give pretty much any mission a go, John boasts a remarkable aviation career. Whats more, hes a natural-born story-teller, and the adventures he recounts are utterly gripping.

Somewhere, up ahead, someone is bleeding, but I have to put that out of my mind. My job is negotiating with time and space. I have my clock, they have theirs. And, in the end, whether the rate at which my clock is ticking matches his is out of my control. Im just the taxi driver here.

There are factors that are within my control. My eyes scan the instruments from time to time as reflexively as my eyelids lower to blink. Condition normal, they tell me. Revolutions per minute are normal, if toward the higher end of the range. Airspeed is satisfactory, and while I can only guess at speed over the ground until I regain GPS coverage, I assume Im making good. Oil pressure, temperature, normal. Fuel burn well, Grant Biel is sitting beside me doing the calcs, and that is a big comfort. He has an almost instinctive feel for the rate at which the engine drinks jet fuel. Hes talking to Dave Brown in the Piper Navajo we have overhead, which is monitoring wind direction and speed, looking for anything that might blow in our favour.

Every now and then my mind strays to consider another reflex what would happen in the event of engine failure, or some other such disaster. The answer is pretty simple, really: Id auto-rotate into the Southern Ocean, somewhere in the darkness down there below, and hope to arrive in good enough shape to launch the raft and get clear of the aircraft. But I dont dwell on this. Ive practised the auto-rotation enough times, and Ive mentally rehearsed the other steps time and again over the years. And I have implicit faith in the maintenance team and their systems. Of all the things that can go wrong, mechanical failure is the least likely.

I think ahead. Thats where the real danger lies.

If I were the worrying kind, Id be wondering whether there would be cloud cover, and whether Id find a way down. Id be thinking about the wind velocity and obstructions in the vicinity of the landing zone. Id be fretting over the quality of the landing zone itself, and whether Id be able to set down close enough to the injured man to be useful.

But Im not worried. There is no point in worrying about any of that, as its out of my control.

The thoughts that are hardest to put out of my mind are those of the man himself. His injuries are massive, Ive been told. Hes losing blood and, as usual in these emergencies, the clock is ticking. There have been lots of studies showing how vital it is to get timely assistance to trauma patients. Paramedics speak of the golden hour, by which they mean the dramatically improved outcome when advanced medical care reaches the afflicted person within 60 minutes. For every minute after that hour has lapsed, the chance of a positive outcome falls away.

I cant help doing the maths: distance to destination divided by likely speed over the ground yields the remaining flight time. For the man Im beating towards, the golden hour lapsed long ago, and many more minutes will pass before I reach him.

As usual, theres a little surge of adrenaline at the thought. But its important to keep focused on the here and the now. He has his clock, I have mine.

There are certain stock phrases that I use to describe to the press what must be done: keep the aircraft right way up and roughly level. And when people tell me that my job must be tremendously exciting, I tend to reply that its a mixture. Hours of boredom, I tell them, and moments of terror.

Grant has word from Dave that there is a favourable wind at higher altitude, so I put the helicopter into a steady climb. Other than that, there is nothing much more to do than scan the instruments and keep the helicopter pointed toward the patient. Theres no point in wasting sympathy on poor Pat Wynne, whos crammed in back there amongst his medical supplies, his kit and the three drums of fuel. Hes been with me on so many of these jobs, he knows the drill.

I look ahead. Theres nothing to see, of course, because the sun isnt due to rise for another three hours, but its habit. And its because I know that somewhere in that direction a man is bleeding.

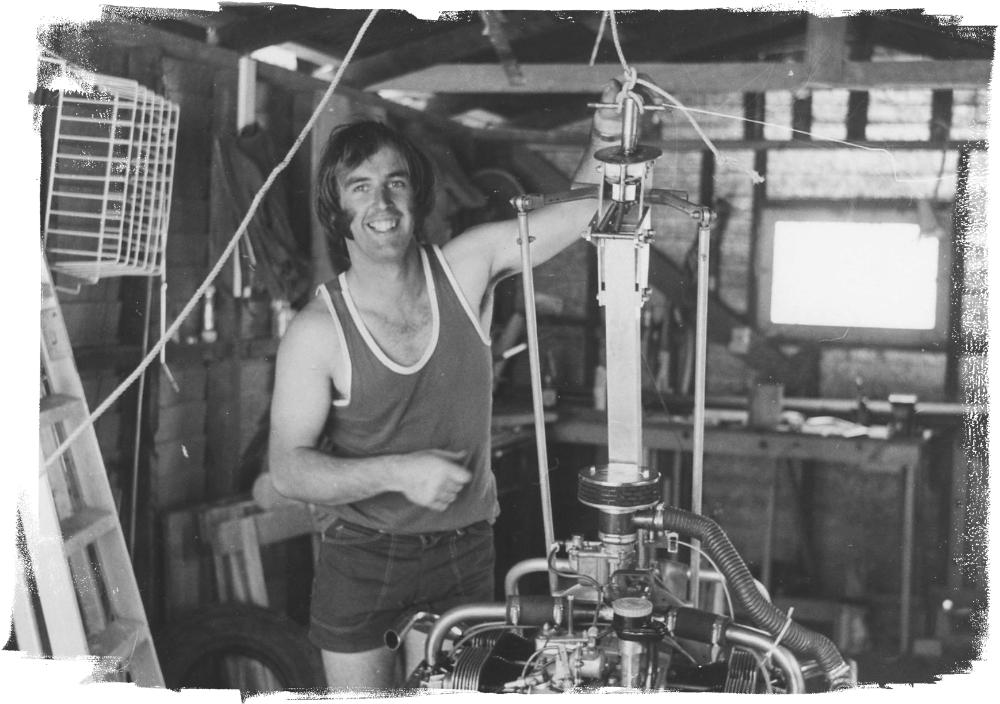

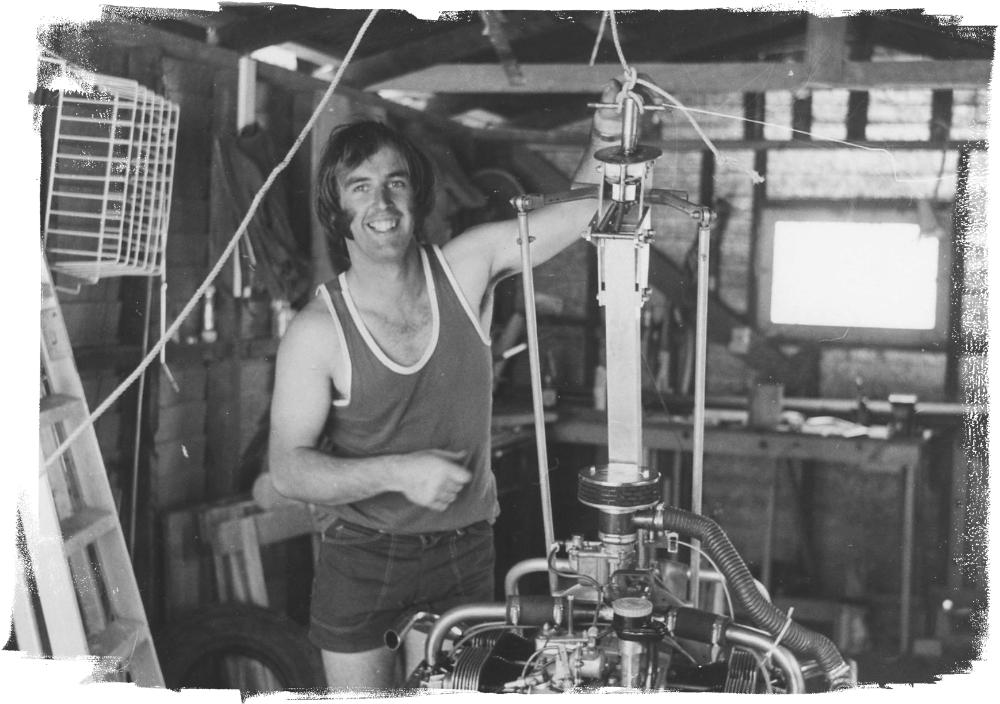

My first venture into rotary wing aircraft: a Bensen gyrocopter I built from plans in the 1970s.

I was high above the ground, relatively speaking. I was in a tree at the back of the property. I reached for a branch, missed my grip and, with a terrible swooping feeling in the pit of my stomach, I fell.

My first landing wasnt one of my better ones. I struck a picnic table on the way down, my right arm taking the full impact. The air was driven from my lungs. I lay there stunned for a minute or two, as my brain tried to catch up with what had just happened to my body. Tough, tree-climbing kids dont cry. After I told Mum what happened, she took me to Palmerston North Hospital, where my arm broken, as it happened was seen to. The doctor heard about the tree. He heard about the fall.

What were you trying to do, young fellow? he asked, not unkindly. Fly?

I nodded sheepishly.

I grew up on my parents dairy farm at Oroua Downs in the Manawatu, about 10 kilometres north of Foxton. The Funnells came from Australia most immediately: my granddad and grandmother came over on the Monowai in 1905, arriving in Wellington. They settled at Raumai near Ashhurst, where Granddad plied his trade as a blacksmith building bridges and shoeing horses. My grandmother, meanwhile, steadily built up a herd of dairy cows, and it was largely the proceeds of her milking operation that enabled them to put a deposit on the 245-acre property at Oroua Downs in 1919. So thats where my dad, Lionel, and his two brothers, Monowai and Darcey, grew up, too.

Probably influenced by his own fathers practical bent, Dad learned how to use a forge. (I can recall as a young boy having to wind furiously on the handle that drove the fan, forcing air into the forge to heat the metal that Dad was working.) When World War II broke out, he enlisted in the army and was assigned to the 6th Field Company of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, holding the rank of sapper. His particular area of expertise was in clearing minefields.