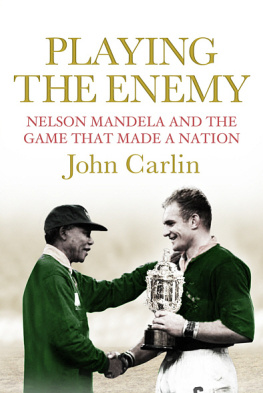

Knowing Mandela

Playing the Enemy: Nelson Mandela and the Game That Made a Nation

CONTENTS

The race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong... but time and chance happeneth to them all.

ECCLESIASTES 9:11

B ALANCING ON the stumps of his amputated legs, gripping a black 9 mm pistol with both hands, he fired four shots through a door in the upstairs bathroom of his home. Behind the door was a small toilet cubicle. A person was inside.

Bewildered and in shock, he staggered towards the door, tried the handle. It was locked. Seconds later, Oh my God! What have I done?

His ears so deafened by the sound of the gunshots that he could not hear his own screams, he rushed down a narrow corridor to his bedroom, holding onto the sides of the walls to keep himself from falling over. He opened a sliding door in the bedroom that gave onto an outside terrace and shouted, Help! Help! Help! At his bedside were his prosthetic legs. He pulled them on, ran back to the bathroom and attempted without success to kick the door down. His screams ever more frantic, he returned to the bedroom, grabbed a cricket bat he kept in case of attack by an intruder, ran back to the bathroom and bashed at the door with desperate fury. A wooden panel gave way, allowing him to reach a hand through and undo the lock. And there he found her, his girlfriend, crumpled on the floor with her face on the toilet seat, her blue eyes vacant, blood pumping from her arm, her hip and her head. She was not moving but maybe, he yearned to believe, she still breathed. Almost fainting from the rotting metal stench of her wounds, battling to get a purchase on her soaked, slippery frame, he eased her off the toilet seat and, with a hand on her head, oozing blood, placed her down on the bathrooms white marble floor, sobbing and screeching, beseeching God to let her live. He found a towel, knelt over her, tried hopelessly to staunch the blood pouring out of the wound on her hip and stared, howling in despair, at her shattered skull and lifeless eyes as the truth began to sink in that not even God could repair the impact of a bullet to the brain nothing could amend the irreversible immensity of this horror.

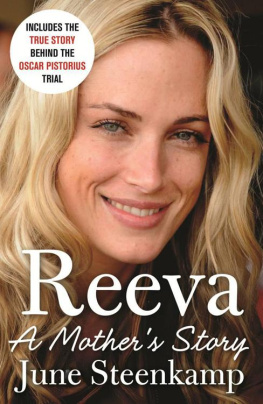

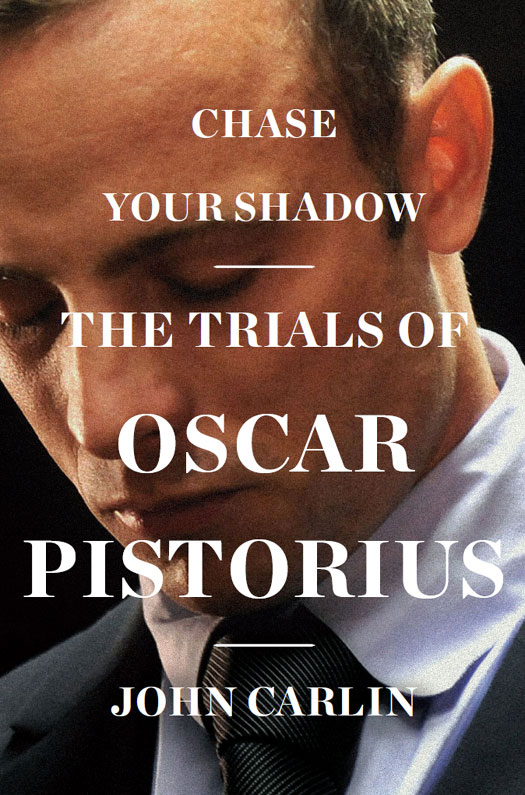

The date was February 14, 2013, Valentines Day. The time he fired the shots, between 3.12 and 3.14 in the morning. The place, his home at Silver Woods Estate, a heavily guarded residential compound in the eastern suburbs of Pretoria, the capital of South Africa. He, Oscar Pistorius, the Blade Runner at twenty-six, a world-famous athlete, the first disabled runner to compete in the Olympic Games, the fastest man with no legs. His victim, Reeva Steenkamp, a twenty-nine-year-old model and aspiring reality TV star, unknown outside South Africa, whom he would propel, in death, to global fame.

At 3.19 he made the first phone call, to his neighbor and friend Johan Stander, the manager of Silver Woods. The phone records would show later that the call lasted twenty-four seconds. Johan, please, please come to my house, he cried. I shot Reeva. I thought she was an intruder. Please, please, please come quick. Then he phoned the emergency services, but they told him he should try and get her to a hospital himself. And then he phoned the estates security guards. He made the three calls in the space of five minutes.

With immense effort, grunting, sobbing and gasping for air, he lifted up her drenched body, carried her out of the bathroom and down a passageway towards a set of grey marble stairs, her head hanging limply on his left shoulder. The gun he had fired did not have normal bullets in the magazine. If they had, she might have survived. But he had used dumdum bullets that, instead of simply penetrating their target, expanded on impact.

When he was halfway down the stairs with the dead or dying woman in his arms a security guard called Pieter Baba came in through the front door, joined moments later by Stander and Standers adult daughter, Carice. Standing there too, was a young man from Malawi called Frankie Chiziweni who lived on the premises, downstairs, and worked for Pistorius as a gardener and housekeeper.

Through his tears he saw the four of them staring up at him, their hands covering their faces, muffling their gasps. He howled at them for help, but for a shocked instant they stood rooted where they were, not wanting to believe what their eyes were seeing. But, yes, that was Oscar Pistorius, the national hero, their gentle, well-mannered friend; that was Reeva, the smiling, warm photographic model that all four of them had seen visiting the estate in recent months. She was in T-shirt and shorts, her long legs dangling from his arms. He wore only a pair of shiny basketball shorts which reached down to his knees, covering the tops of his skin-colored prostheses with their plastic calves, feet and toes. Blood trailed behind him on the staircase, trickled down his back. Blood on her clothes, her matted blonde hair, on his shorts, his legs, his bare torso and shoulders streams of it.

Stander, the oldest of the four, was the first to collect himself, calling out that an ambulance was on its way and urging Pistorius to lay Reeva down on a rug by a sofa in the sitting room, near the front door. He dropped to his knees, lowered her delicately onto the ground and screamed that he wanted that ambulance now, as he scrutinized her bruised face for some sign of life. He put a finger between her lips, trying to prise open her mouth, as if that would make her breathe. With his other hand he covered the wound on her crushed right hip, where the bleeding was heaviest. The gestures were as futile as they were desperate. There was no sign of breathing, no end to the haemorrhage. Carice Stander placed a towel on Reevas hip, asked him if he had some rope or some tape to staunch the blood in the third wound, on her left arm, conspiring with him in the frantic, make-believe struggle that they could do something, anything, to bring her back to life. Ten minutes had passed since he had fired the shots. Her eyes were closed and she made no sound. He fingered the inside of her wrist, searching for a pulse, finding none. Please, God, please, let her live, she must not die! he prayed. Stay with me, my love, stay with me!

Two minutes after the others a fifth witness entered the house, a doctor called Johan Stipp, who lived a hundred yards away and had been woken by the sound of the shots.

What happened? the doctor asked.

I shot her. I thought she was a burglar. I shot her, he cried, still with his fingers in her mouth, trying to force a way in between her teeth, which were clenched shut.

Dr Stipp was a radiologist and no expert in an emergency, but he went through the motions of checking for signs of life, expecting to find none for he saw that the top of her skull had cracked open and brain tissue was leaking out of it. He felt her wrist: no pulse. He opened her right eyelid: no contraction of the pupil. She was brain-dead, mortally wounded.

An ambulance arrived at 3.43. Two paramedics walked into the house and confirmed the doctors diagnosis, pronouncing her dead.

Sobbing, beyond hope of Gods mercy now, he retreated up the stairs. Carice Stander panicked. She realized the gun must be up there and feared he would do what she herself might have done in his place. She followed him upstairs, trying to think what she could do to try to stop him from shooting himself but there was no need. He just stumbled about the corridor that led to his bedroom, in a haze of tears. A part of him longed for death. Whether it came to that or not, he would first need understanding and forgiveness from someone close to him, someone who would spread the word. He sought that now, not in his family, who would be sure to be on his side, but in a friend called Justin Divaris, the person who had introduced him to Reeva. Pistorius went to his bedroom, got his mobile phone and called Divaris. It was five to four in the morning.