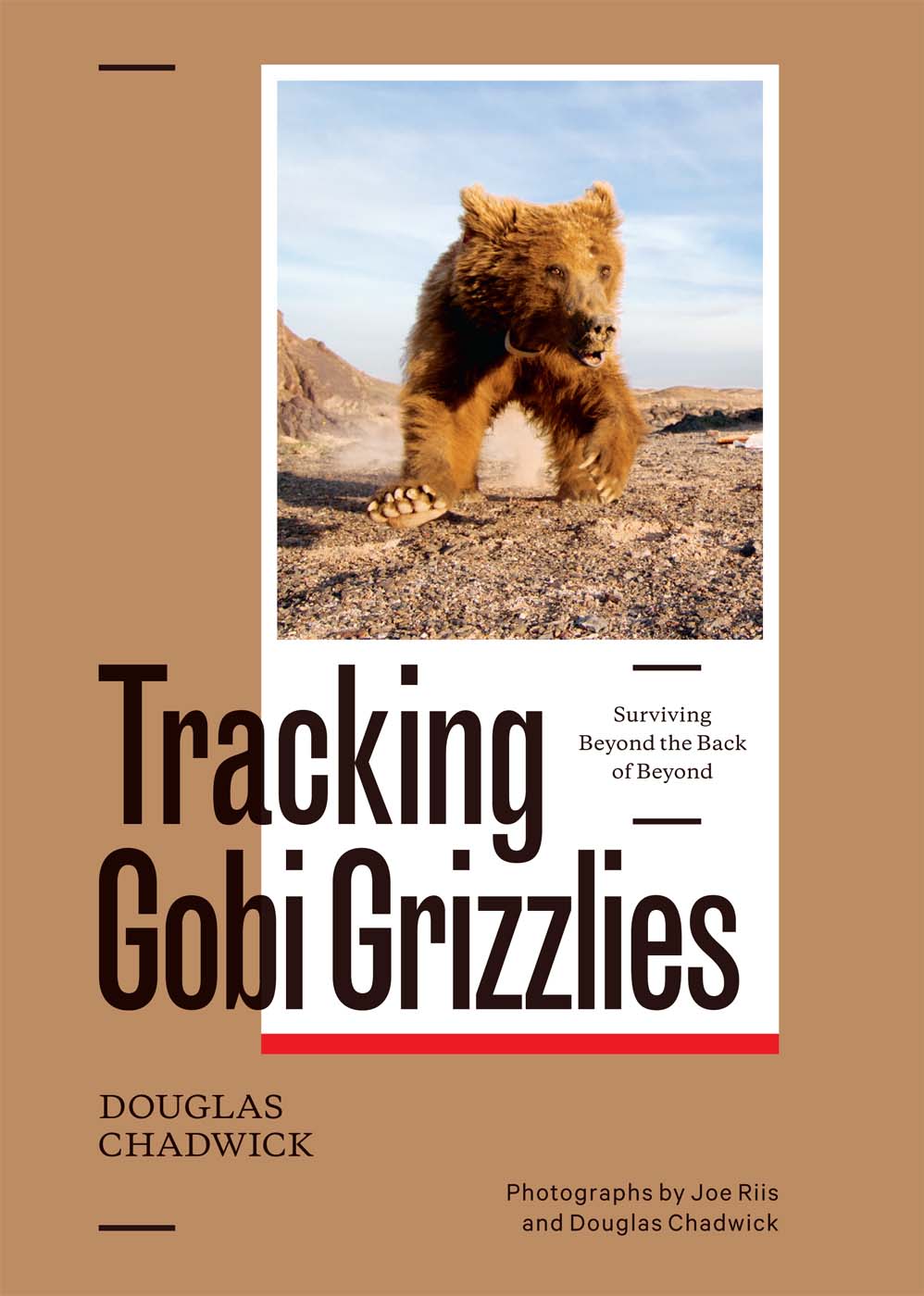

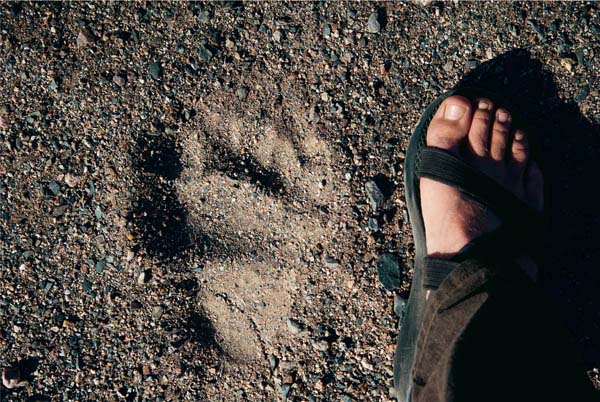

Bears and humans are among the few mammals that rely on plantigrade locomotionusing the full bottom surface of their feet, including the heels (and palms, in the bears case). Photo: Joe Riis

Tracking Gobi Grizzlies

Surviving Beyond the Back of Beyond

Patagonia publishes a select number of titles on wilderness, wildlife, and outdoor sports that inspire and restore a connection to the natural world.

Copyright 2017 Patagonia

Text Douglas Chadwick. All photograph copyrights are held by the photographers as indicated in captions. Maps by Maps for Good.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher and copyright holders. Requests should be mailed to Patagonia Books, Patagonia, Inc., 259 W. Santa Clara St., Ventura, CA 93001-2717.

FIRST EDITION

Editors: Abraham Streep & John Dutton

Art Director: Scott Massey

Photo Editor: Jane Sievert

Project Manager: Jennifer Patrick

Production: Rafael Dunn

Additional Design & Photo Editing Support: Jennifer Ridgeway

Director of Patagonia Books: Karla Olson

Printed in Canada by Friesens

on 100% recycled paper

ISBN 978-1-938340-62-8

E-Book ISBN 978-1-938340-63-5

Library of Congress Control Number 2016912364

One percent of the sales from this book go to the preservation and restoration of the natural environment.

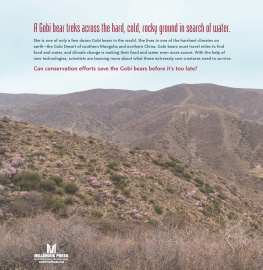

Base camp in the eastern mountain complex of Great Gobi Strictly Protected Area (GGSPA). Photo: Doug Chadwick Collection

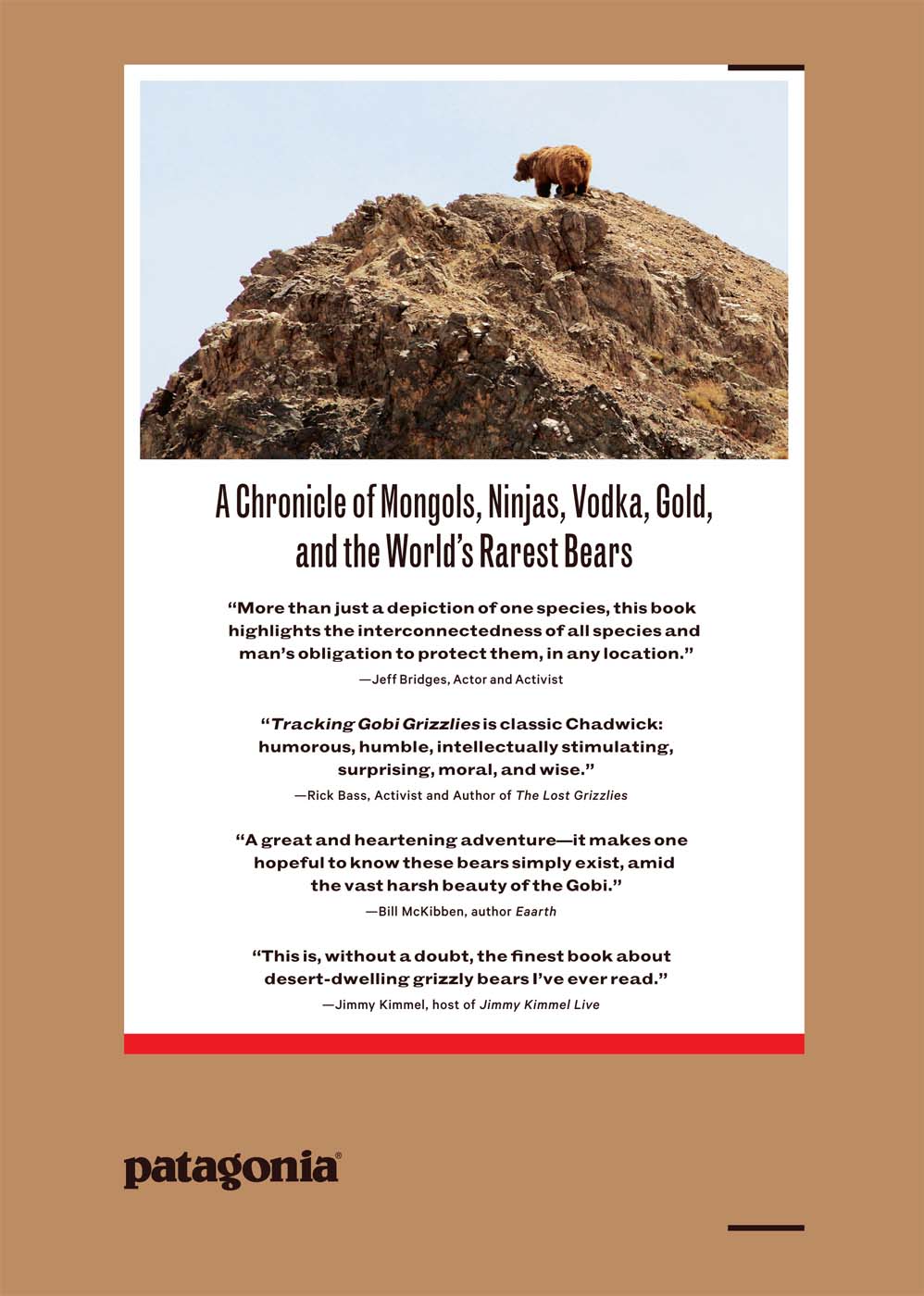

This female is one of the last three to four dozen Gobi grizzly bears, Ursus arctos gobiensis, left on Earth. Known as mazaalai in Mongolian, all of them live in southwest Mongolias GGSPA. Photo: Doug Chadwick

Preface

Two Quick Bear Stories

For more than a decade, my home was a log cabin in the Montana Rockies, off the grid and way off the clock. My to-do list on many days looked like this:

Chop firewood,

Pump water,

Go watch wildlife next door in Glacier National Park,

Especially bears.

Late one August, I camped for a while along the ridgeline of a mountain range overlooking a series of shallow subalpine lakes. It was huckleberry time, and the crop up there was beyond good that year. You could have told as much from the purple stains that tattooed my fingers and encircled my mouth. Or from the big clods of what looked like compressed pie filling all over the slopes. They were the dung left by tonsliterallyof grizzlies drawn to huck heaven from home ranges near and far.

Before long, I had an adult bear in view at a lake. I dropped from the ridge to a lower band of ledges and set up a telescope. The animal was wading out from shore with only portions of its back and snout showing, furry alligatorstyle. This grizzly wasnt in the water to hunt for fish or for anything else, though. It wasnt there to drink its fill or to interact with another bear. It was just doing what any of us might while free-roaming the slopes on a hot afternoongetting wet and keeping cool. Feeling fine. Every so often, the bear would stand to swipe at the surface or pound it with its paws to create a splash. At other times, Aqua-Grizz would submerge completely and then rise on its hind legs again to shake itself, whipping rings of water from its head and upper torso.

Returning to shore, the bear came upon a washed-up tree trunk. After rolling this around for a few moments, the grizzly lay on its back among the green sedges, wrestled the heavy length of wood atop its body, lifted it, and began to juggle the thing with all four feet. Why? Well, why will a grown-up grizzly repeatedly slide down a tilted patch of snow? Why does one foraging in a meadow sometimes break into a wriggly, loose-limbed frolic, swinging its head and zigzagging this way and that? I think the better questionand also the answeris: Why not? Imagine you own hundreds of pounds of muscle packed atop muscle, claws that measure three to four inches along the outside curve, and the ability to accelerate from zero to thirty-five miles per hour in seconds. What you want to do, you can do, no worries. Youre a heavy-duty organic power generator with a fresh tank of fruit sugar fuel, and this log is just lying there waiting to be tossed around.

While science cant quite bring itself to say that grizzlies like to goof, the experts acknowledge that, young or old, these bears do devote an intriguing amount of time to play behavior. Exuberance is part of what defines them. So is a strongly developed sense of curiosity. Grizzlies are given to thoroughly investigating objects of interest, manipulating them with their mouth as well as with those broad, flexible paws, trying in their own way to learn more about how the world works. Its one of the main reasons Ive always found it natural to relate to grizzto imagine myself in their place as they move through a landscape, poking around. I also try never to forget that the same animals can instantly turn volcanic when upset.

The grizzly eventually lost interest in the log and waded back into the lake. There, the bear resumed whapping the water with its paws, alternately dunking and rising to do the subalpine swimming hole shimmy-shake. For a few minutes, it spent more time than usual with its head underwater. I thought the bear might be investigating something below. That was before a closer look through the telescope revealed that it was blowing bubbles with its nose. The waters surface tension, layered with a fine summer film of pollen and dust, kept many of the bubbles bulging in place after they rose, glistening atop the lake like a flotilla of small jellyfish. The grizzly bit at some. It stood upright once more, chest-deep now, and appeared to look the bubbles over carefully. Then it started popping the largest by pricking them one by one with the tip of a claw.

MY WIFE, KAREN REEVES, SPENT SEVERAL SUMMERS MANAGING A HIKE-IN chalet high in the Glacier Park backcountry. One year, a spell of rain wrapped the heights in heavy clouds, hiding the spectacular topography from sight for days. One of the guests, a woman with an infant child, grew more and more restless as the storm kept its shroud over the land. At last, she decided that, rain or no rain, view or no view, she and her husband were going to get out on the trail to a pass south of the chalet. The high point was barely a mile distant, but the route was steep. By the time the couple negotiated the pass and started through the alpine meadows beyond, their baby had grown hungry. Picking out a level spot, the woman sat, opened her jacket, and began to suckle the child amid veils of mist.