Foreword

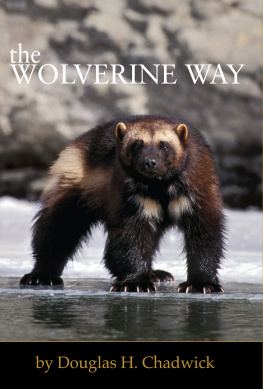

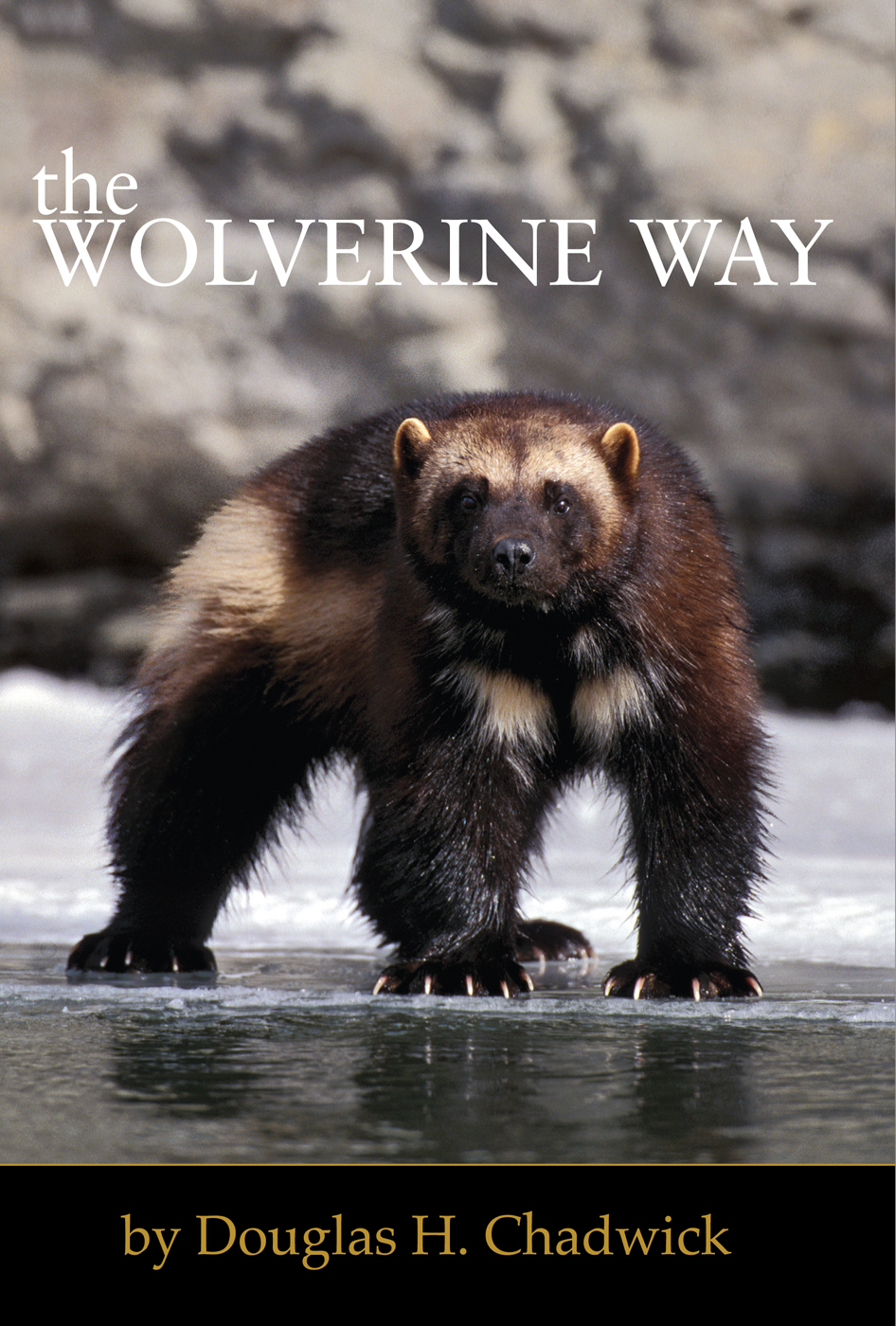

Most people, even if they dont know any of the details about the natural history of wolverines, know that they are fierce. Maybe its the name wolverine with that core root wolve that leaves a sense of distilled, implacable fierceness. Or maybe its a memory of a tale of some hapless victim human or otherwise who had the misfortune of crossing paths with a wolverine.

But take the time to look into their natural history, and you come across facts such as the observation that wolverines sometimes force grizzlies off a kill. When you weigh 30 pounds that, as Doug Chadwick tells us, is pretty badass. You also discover that while wolverines turn out to have a surprisingly sociable side to them, they remain mostly solitary for much of the year and claim huge amounts of territory that they fiercely protect. You also find out they travel widely, covering hundreds of miles a year, and if they are to survive into the future they need space to move around in. They need the freedom to roam.

At the clothing company Patagonia we are committed to using our company to implement solutions to the environmental crisis. A few years ago we decided to focus resources on the protection of wildlife corridors, so that animals had the ability to move within and between territories, ensuring genetic diversity. Borrowing the name from a book by the celebrated wildlife photographer Florian Shultz for which Doug Chadwick wrote the introductory chapter, we called the initiative Freedom to Roam. We soon spun it off as an independent nonprofit coalition representing an array of constituencies, including large corporations, government agencies and environmental nonprofits.

One of the goals of Freedom to Roam is to increase awareness of what wildlife corridors are. Another is to highlight why in the face of the dual pressures from habitat fragmentation, due to human development, and habitat shift, due to global warming corridors are the best bet for wildlifes survival into the next century. At Patagonia we knew the way to increase awareness of wildlife corridors was to tell stories about this concept of landscape connectivity. In the case of Freedom to Roam, that meant telling good animal stories.

So we approached one of the eminent animal storytellers of our time, Doug Chadwick, and soon he delivered an essay about wolverines to be printed in one of our catalogs. When I say these might be the toughest animals in the world, Chadwick wrote, Im including the way wolverines relentlessly roam vast territories taking on cliffs, icefalls, and summits through some of the nastiest weather modern winters can throw at a mammal. Climbers and extreme skiers come back from such expeditions and tell riveting tales of survival. Wolverines just growl and keep going 24/7.

Chadwicks essay resonated with our customers, and we suspected we might have identified the four-legged mascot we were searching for that could catch peoples attention long enough that they would listen to the bigger message of large-scale habitat conservation. In the initial stages of building the coalition, we received an invitation from Governor Freudenthal of Wyoming to give a presentation on Freedom to Roam at the annual meeting of the Western Governors Association. As host of the meeting Freudenthal was tasked with setting the agenda, and he wanted to propose to the other governors that they consider the importance of protecting wildlife corridors in their states.

The meeting was in Jackson Hole; there were 600 people in the audience, including the 14 governors and their staffs, four premieres from Canadas border provinces, dozens of corporate CEOs and government officials of all stripes. I narrated the presentation, showing slides and maps and animations as I told them about Freedom to Roam.

The highlight though was the story of M3, the biggest, snarliest and most badass wolverine any of the biologists had ever encountered. I told how wildlife biologists finally managed to trap M3 and put a radio collar on his neck programmed to uplink his position every five minutes. I told how the biologists were then astounded to learn how far a male wolverine roams, as they observed M3 leaving Montana, heading north into Waterton, cruising over to British Columbia and working his way back to Montana.

The most astounding thing they observed, however, was when M3 left Montana in February, the height of winter. To get to Waterton, I told the crowd, M3 approached the base of Mount Cleveland and then started up the south face 9,000 feet, 9,500 feet, 10,000 feet. On the screen I had an artists rendition of Mt. Cleveland, with a progression of dots showing M3s position as he climbed the steep south face, gained the ridge and kept going toward the summit. Finally M3 topped out on the highest peak in Glacier National Park, I said. Why? You guessed it: Because it was there.

M3 got a thunderous applause, and when I finished my presentation Governor Freudenthal gave me a bear hug, Governor Schweitzer from Montana high-fived me, Governor Napolitano from Arizona said she was a Freedom to Roam convert, and we heard months later that while on a fact-finding trip on global warming in the high Arctic, Governor Ritter from Colorado regaled his shipmates with a retelling of the story of the most badass wolverine of them all.

What you have in front of you is that story of M3 and the story of what we have discovered about wolverines. All told by Doug Chadwick from the research of committed field biologists like Jeff Copeland and Rick Yates. Its an adventure story, a surprising story a badass story.

Rick Ridgeway

Prologue

The author, age 6 or 7, and his mining geologist father, Russell Chadwick, at a prospecting camp in the western Rockies. CHADWICK COLLECTION

The Way is limitless,

So nature is limitless,

So the world is limitless,

And so I am limitless.

LAO-TZU

from the Tao Te Ching, translation by Peter Merel

WHEN I WAS 17, I SPENT THE SUMMER WITH MY GEOLOGIST FATHER prospecting a rolling sweep of Alaskan tundra northeast of Nome. We traveled miles downstream one day to visit the nearest neighbor, though he was anything but a neighborly man. He was a hermit who sought out people only when he desperately needed supplies. A rusty generator ran near his camp and powered a high-pressure hose. He used the stream from its nozzle to bust loose the gravels of an old riverbed and sift them for gold. Yet unlike any placer-mining operation Id ever seen, his took place underground. This man had sluiced his way inside the hills, carving tunnels and caverns through the permafrost.

The floor of the mine, where the water drained, was a half-congealed sludge that grabbed at our boots. The walls and ceilings were rimed with icicles and frost patterns sparkling like subterranean galaxies when we played a flashlight across them. Our strange, reluctant host used no posts to shore up the roof of this burrow. Portions had fallen onto the floor in heaps. It seemed only a matter of time before one of the rooms he kept enlarging collapsed to entomb him in crystals and muck and perhaps a few flakes of gold.

I studied the hermits face below the cone of light from his headlamp, taking care to keep my own light pointed somewhere else so he wouldnt catch me staring. His skin was striated with welts. The sections in between didnt fit together right. Some patches looked like dried-out hamburger. The movements of light beams and shadows made the overall effect even more grotesque, as if his features were writhing. I could understand why he preferred solitude. I had no way of knowing whether or not his appearance was what drove him to accept this level of risk while mining. Though young, Id seen ordinary-looking men do amazingly heedless things to follow a streak of gold in the ground. Still, the questions kept revolving in my mind: What was going on with this hermit? What in the world would leave a man with this wreck of a visage?