Paul Czanne

Titles in the series Critical Lives present the work of leading cultural figures of the modern period. Each book explores the life of the artist, writer, philosopher or architect in question and relates it to their major works.

In the same series

Antonin Artaud David A. Shafer

Roland Barthes Andy Stafford

Georges Bataille Stuart Kendall

Charles Baudelaire Rosemary Lloyd

Simone de Beauvoir Ursula Tidd

Samuel Beckett Andrew Gibson

Walter Benjamin Esther Leslie

John Berger Andy Merrifield

Jorge Luis Borges Jason Wilson

Constantin Brancusi Sanda Miller

Bertolt Brecht Philip Glahn

Charles Bukowski David Stephen Calonne

William S. Burroughs Phil Baker

John Cage Rob Haskins

Albert Camus Edward J. Hughes

Fidel Castro Nick Caistor

Paul Czanne Jon Kear

Coco Chanel Linda Simon

Noam Chomsky Wolfgang B. Sperlich

Jean Cocteau James S. Williams

Salvador Dal Mary Ann Caws

Guy Debord Andy Merrifield

Claude Debussy David J. Code

Fyodor Dostoevsky Robert Bird

Marcel Duchamp Caroline Cros

Sergei Eisenstein Mike OMahony

Michel Foucault David Macey

Mahatma Gandhi Douglas Allen

Jean Genet Stephen Barber

Allen Ginsberg Steve Finbow

Ernest Hemingway Verna Kale

Derek Jarman Michael Charlesworth

Alfred Jarry Jill Fell

James Joyce Andrew Gibson

Carl Jung Paul Bishop

Franz Kafka Sander L. Gilman

Frida Kahlo Gannit Ankori

Yves Klein Nuit Banai

Akira Kurosawa Peter Wild

Lenin Lars T. Lih

Stphane Mallarm Roger Pearson

Gabriel Garca Mrquez Stephen M. Hart

Karl Marx Paul Thomas

Henry Miller David Stephen Calonne

Yukio Mishima Damian Flanagan

Eadweard Muybridge Marta Braun

Vladimir Nabokov Barbara Wyllie

Pablo Neruda Dominic Moran

Georgia OKeeffe Nancy J. Scott

Octavio Paz Nick Caistor

Pablo Picasso Mary Ann Caws

Edgar Allan Poe Kevin J. Hayes

Ezra Pound Alec Marsh

Marcel Proust Adam Watt

John Ruskin Andrew Ballantyne

Jean-Paul Sartre Andrew Leak

Erik Satie Mary E. Davis

Arthur Schopenhauer Peter B. Lewis

Adam Smith Jonathan Conlin

Susan Sontag Jerome Boyd Maunsell

Gertrude Stein Lucy Daniel

Igor Stravinsky Jonathan Cross

Leon Trotsky Paul Le Blanc

Richard Wagner Raymond Furness

Simone Weil Palle Yourgrau

Ludwig Wittgenstein Edward Kanterian

Frank Lloyd Wright Robert McCarter

Paul Czanne

Jon Kear

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by

Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448, Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2016

Copyright Jon Kear 2016

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Bell & Bain, Glasgow

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780236032

Contents

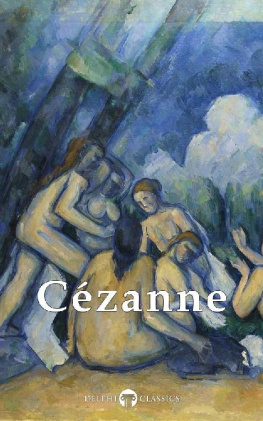

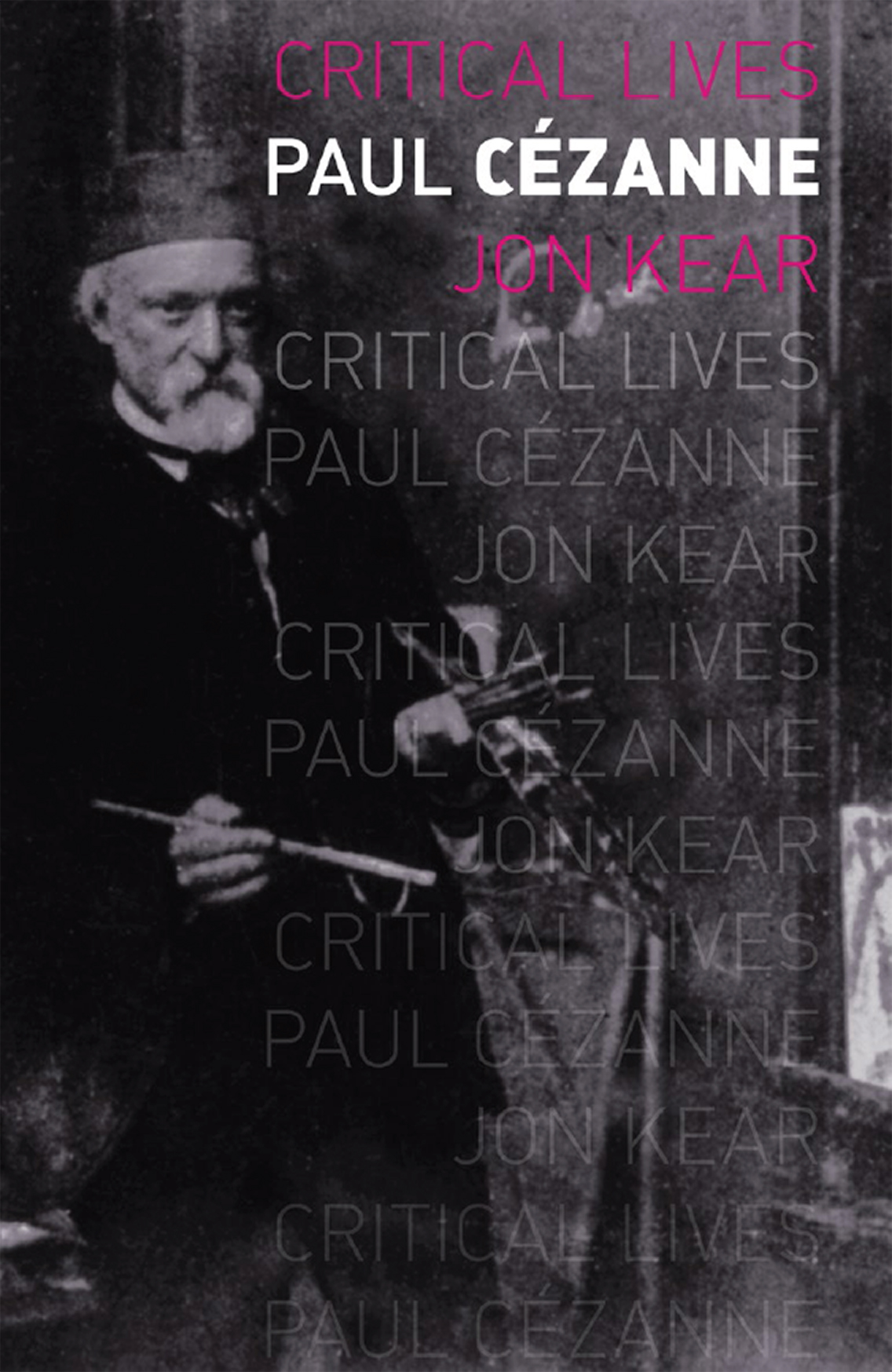

Paul Czanne, in 1904, sitting in front of his Les Grandes Baigneuses, photograph by mile Bernard.

Introduction: The Myth of Czanne

In 1904 mile Bernard, a leading Symbolist painter and critic, made the long trip from Paris to Czannes studio in Aix-en-Provence to interview him for an article he was to publish later that year. During his stay he took several photographs of Czanne. In the most emblematic of these, Czanne poses in the dim light of his austere studio at Les Lauves, his clasped hands resting on his paint-spattered trousers, before a large work propped on an easel: an elderly artist framed by the fantasia of youthful female nudes on the canvas behind him. The painting was one of three ambitious and idiosyncratic large paintings collectively known as Les Grandes Baigneuses (The Bathers) that preoccupied his later years. These show female bathers set on the edge of a stream, basking in the sun or about to enter the water. Czanne worked intermittently on more than one canvas at once, making extensive changes as he went along. The one in the photograph is the version from the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia before it underwent several crucial changes. Czanne had already been labouring a decade on it by then, and it would remain, as its companion paintings would, incomplete at his death. Viewed together as an ensemble, it is clear how interconnected these paintings are and how they were conceived as alternate responses to the possibilities and problems posed by the subject. Preliminary oil sketches indicate that he planned to extend the series.

The large scale of these paintings and the fact that he worked on them for such a protracted period indicate the special value Czanne accorded them. He often remarked to visitors to his studio that these paintings were to be the testing ground for his theories, and it was as such that they were understood by the audience for his painting. They were to become indelibly associated with his legacy. The Barnes version, the first of the series, was clearly intended to be a chef-doeuvre, and was conceived on the eve of his re-entry into public exhibition after a long exile from exhibiting in Paris, though it was not shown in his lifetime.

In 1907 a major retrospective of 56 pictures at the Salon dAutomne in two rooms of the Grand Palais included two of the late Grandes Baigneuses, almost certainly the London and Philadelphia versions, which became the focus of discussion of the artist. By then Czanne was dead, having succumbed to pneumonia the previous autumn, aged 67. Already suffering from the degenerative effects of diabetes over the previous sixteen years, he had collapsed in a rainstorm after a day painting in the fields of Aix and lay unconscious and exposed to the elements for several hours. Despite appearing to recover, within days he had passed away.

In the course of the twentieth century Czanne has subsequently been regarded as the father of modern painting and integral to the canon of modernism. While his landscapes, portraits and still-lifes, as his letters attest, revealed a commitment to an empirical approach to painting sur le motif (in nature), his bathers seemed the antithesis of all this: strange reveries rendered without models that freely reworked the old masters he had studied in the Louvre, yet in a way that seemed quite contemporary in mood and sensibility. Les Grandes Baigneuses appeared at once to reach back to the past, not merely to the old masters but to something more primordial and archaic, and at the same time to be ultra-modern. These works posed many questions about the artist and the conceptual framework of his late painting.