Nathalia Brodskaa

IMPRESSIONISM

and

POST-IMPRESSIONISM

Author: Nathalia Brodskaa

Title: Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

Collection: Essential

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Confidential Concepts, Worldwide, USA

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where

this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN : 978-1-78310-504-5

Contents

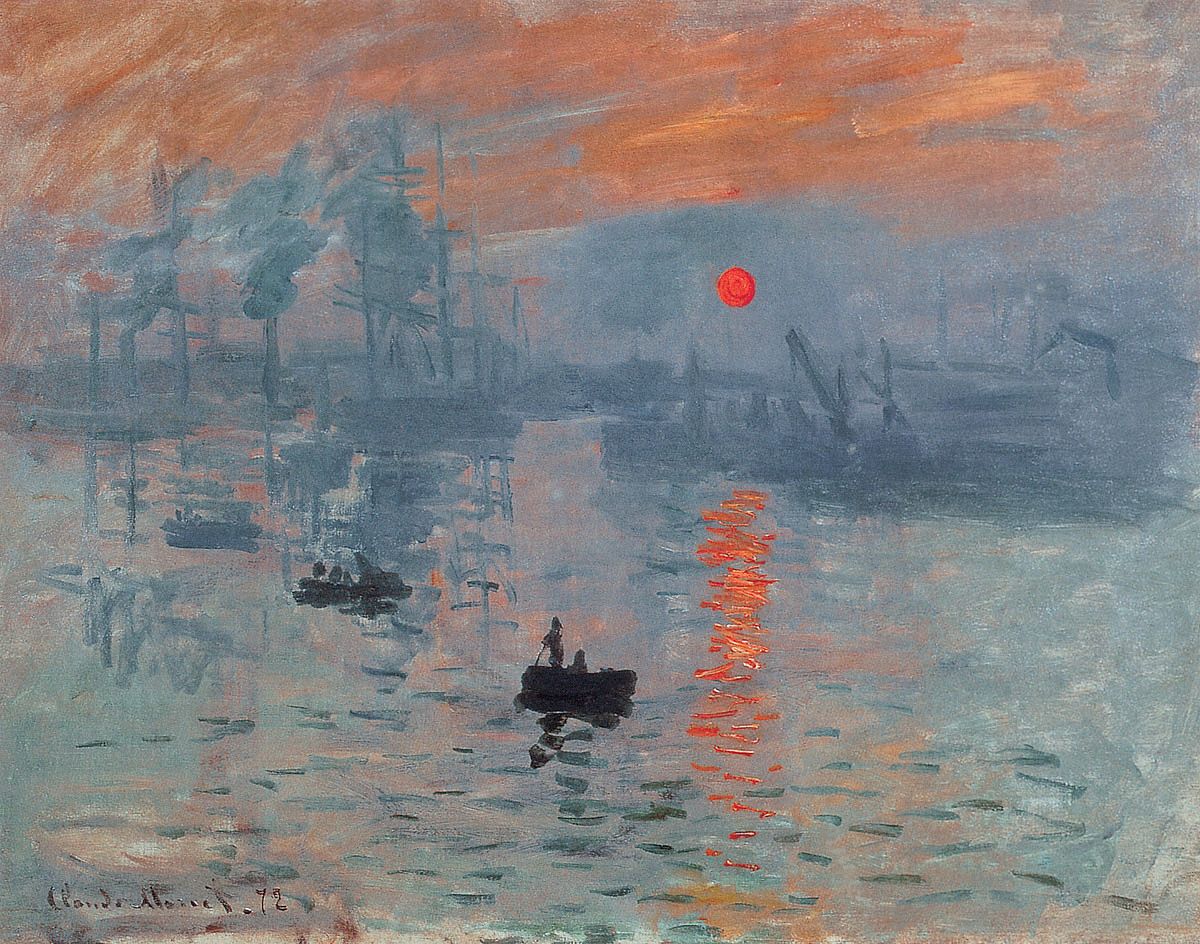

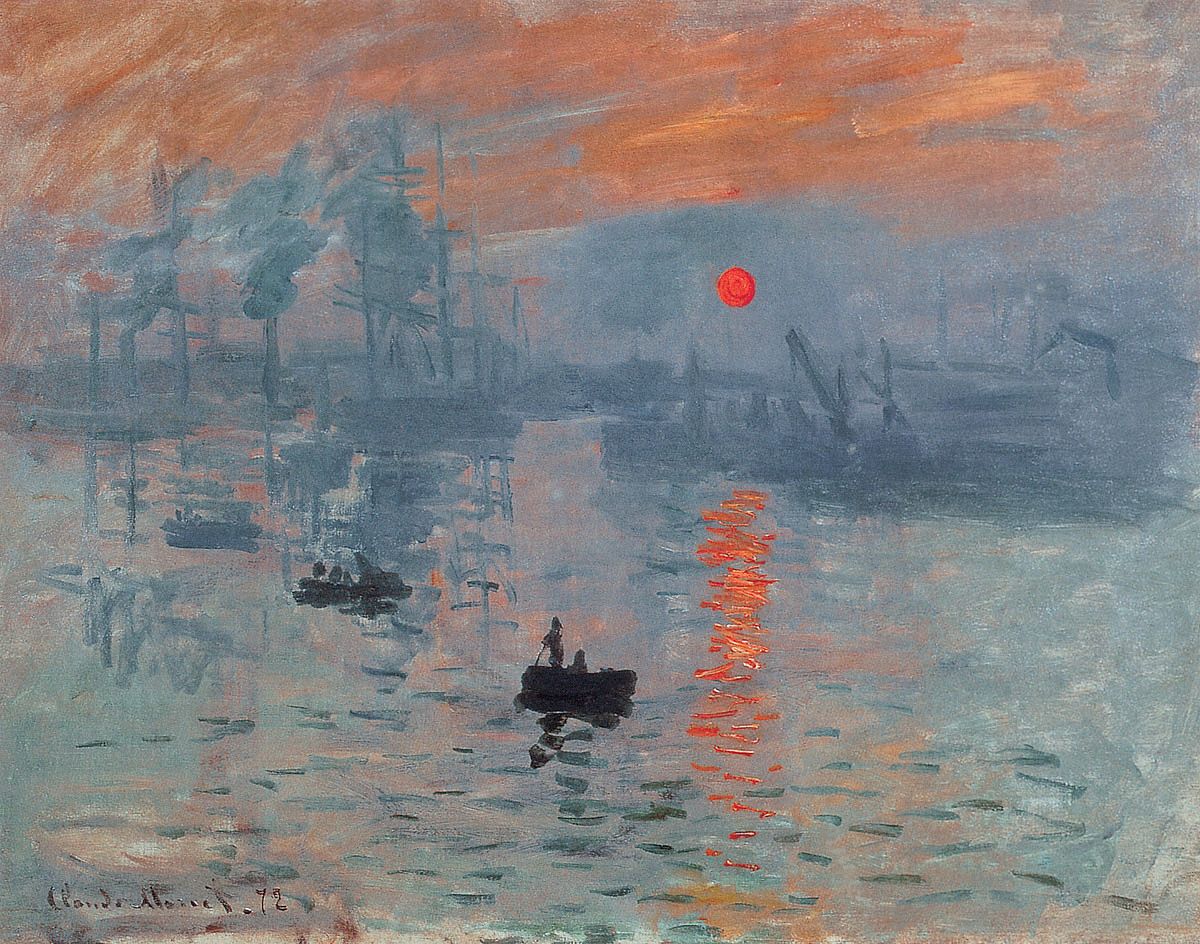

Claude Monet, Impression, Sunrise, 1873. Oil on canvas, 48 x 63 cm. Muse Marmottan, Paris.

Preface

was the prescient title of one of Claude Monets paintings shown in 1874 in the first exhibition of the Impressionists, or as they called themselves then, the Socit anonyme des artistes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs (the Anonymous Society of Artist, Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers). Monet had gone painting in his childhood hometown of Le Havre to prepare for the event, eventually selecting his best Havre landscapes for display. Edmond Renoir, journalist brother of Renoir the painter, compiled the catalogue. He criticised Monet for the uniform titles of his works, for the painter had not come up with anything more interesting than View of Le Havre. Among these Havre landscapes was a canvas painted in the early morning depicting a blue fog that seemed to transform the shapes of yachts into ghostly apparitions. The painting also depicted smaller boats gliding over the water in black silhouette, and above the horizon the flat, orange disk of the sun, its first rays casting an orange path across the sea. It was more like a rapid study than a painting, a spontaneous sketch done in oils what better way to seize the fleeting moment when sea and sky coalesce before the blinding light of day? View of Le Havre was obviously an inappropriate title for this particular painting, as Le Havre was nowhere to be seen. Write Impression, Monet told Edmond Renoir, and in that moment began the story of Impressionism.

On 25 April 1874, the art critic Louis Leroy published a satirical piece in the journal Charivari that described a visit to the exhibition by an official artist. As he moves from one painting to the next, the artist slowly goes insane. He mistakes the surface of a painting by Camille Pissarro, depicting a ploughed field, for shavings from an artists palette carelessly deposited onto a soiled canvas. When looking at the painting he is unable to tell top from bottom, or one side from the other. He is horrified by Monets landscape entitled Boulevard des Capucines. Indeed, in Leroys satire, it is Monets work that pushes the academician over the edge. Stopping in front of one of the Havre landscapes, he asks what Impression, Sunrise depicts. Impression, of course, mutters the academician. I said so myself, too, because I am so impressed, there must be some impression in here and what freedom, what technical ease! At which point he begins to dance a jig in front of the paintings, exclaiming: Hey! Ho! Im a walking impression, Im an avenging palette knife (Charivari, 25 April 1874). Leroy called his article, The Exhibition of the Impressionists. With typical French finesse, he had adroitly coined a new word from the paintings title, a word so fitting that it was destined to remain forever in the vocabulary of the history of art.

Responding to questions from a journalist in 1880, Monet said: Im the one who came up with the word, or who at least, through a painting that I had exhibited, provided some reporter from Le Figaro the opportunity to write that scathing article. It was a big hit, as you know. (Lionello Venturi, Les Archives de limpressionnisme, Paris, Durand-Ruel, 1939, vol. 2, p. 340).

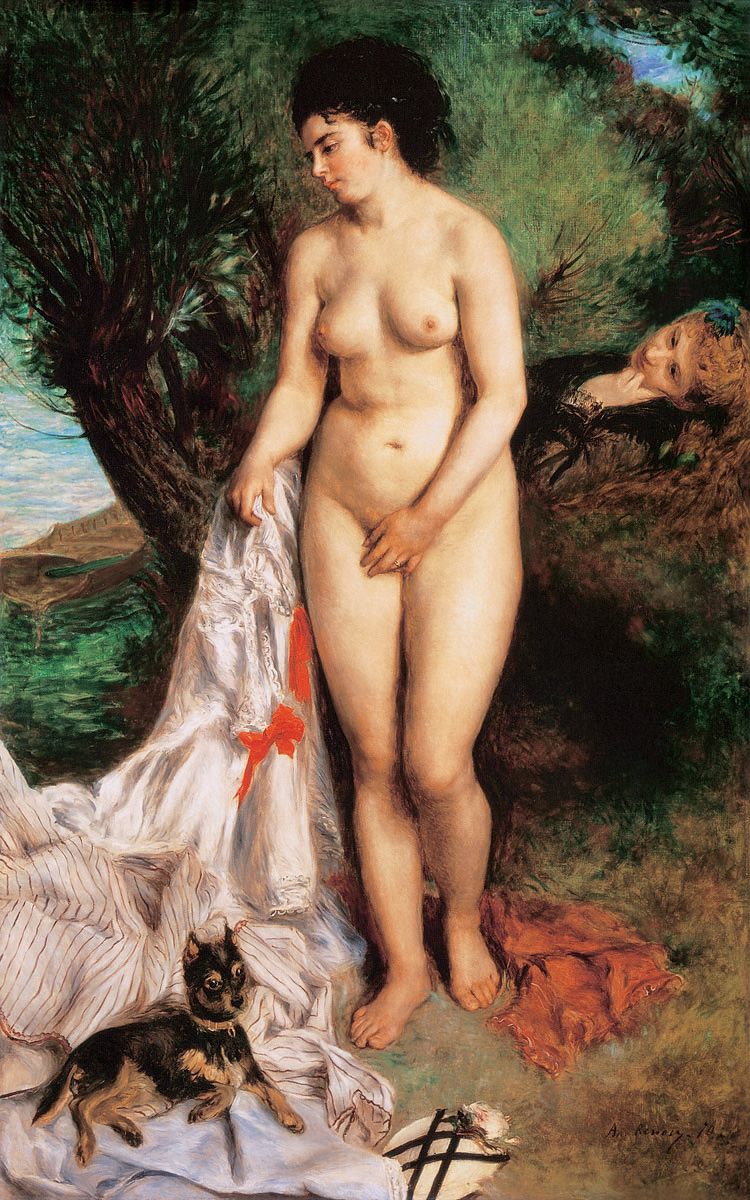

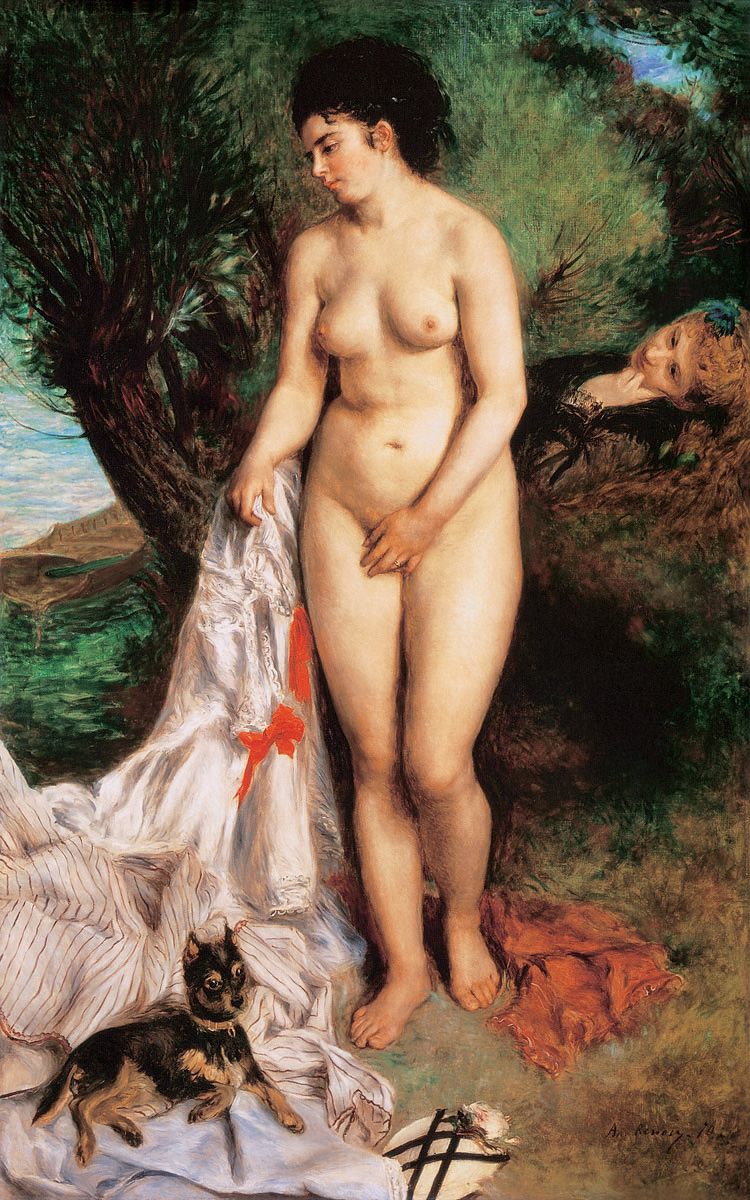

Pierre Auguste Renoir, Bather with a Griffon Dog, 1870. Oil on canvas, 184 x 115 cm. Museu de Arte, So Paulo.

The Impressionists and Academic Painting

T he young men who would become the Impressionists formed a group in the early 1860s. Claude Monet, son of a Le Havre shopkeeper, Frdric Bazille, son of a wealthy Montpellier family, Alfred Sisley, son of an English family living in France, and Pierre Auguste Renoir, son of a Parisian tailor had all come to study painting in the independent studio of Charles Gleyre, whom in their view was the only teacher who truly personified neo-classical painting.

Gleyre had just turned sixty when he met the future Impressionists. Born in Switzerland on the banks of Lake Lman, he had lived in France since childhood. After graduating from the Ecole des beaux-arts, Gleyre spent six years in Italy. Success in the Paris Salon made him famous and he taught in the studio established by the celebrated Salon painter, Hippolyte Delaroche. Taking themes from the Bible and antique mythology, Gleyre painted large-scale canvases composed with classical clarity. The formal qualities of his female nudes can only be compared to the work of the great Dominique Ingres. In Gleyres independent studio, pupils received traditional training in neo-classical painting, but were free from the official requirements of the Ecole des beaux-arts.

Our best source of information regarding the future Impressionists studies with Gleyre is none other than Renoir himself, in conversation with his son, the renowned filmmaker Jean Renoir. The elder Renoir described his teacher as a powerful Swiss, bearded and near-sighted and remembered Gleyres Latin Quarter studio, on the left bank of the Seine, as a big empty room packed with young men bent over their easels. Grey light spilled onto the model from a picture window facing north, according to the rules. (Jean Renoir, Pierre Auguste Renoir, mon pre, Paris, Gallimard, 1981, p. 114). Gleyres students could hardly be less alike. Young men from wealthy families who were playing at being artists came to the studio wearing jackets and black velvet berets. Monet derisively called these students the grocers on account of their narrow minds. The white house painters coat that Renoir worked in was the butt of their jokes. But Renoir and his new friends paid them no heed. He was there to learn how to draw figures, his son recalls. As he covered his paper with strokes of charcoal, he was soon completely engrossed in the shape of a calf or the curve of a hand. (J. Renoir, op. cit., p. 114). Renoir and his friends took art school seriously, to such an extent that Gleyre was disconcerted by the extraordinary facility with which Renoir worked. Renoir mimicked his teachers criticisms in a funny Swiss accent that the students used to make fun of him: Cheune homme, fous des drs atroit, drs tou, mais on tirait que fous beignez bour fous amuser. (Young man, you are very talented and very gifted, but people say that you paint just for fun). As Jean Renoir tells it: Obviously, my father replied, if it wasnt any fun, I wouldnt paint! (J. Renoir,