Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Heather

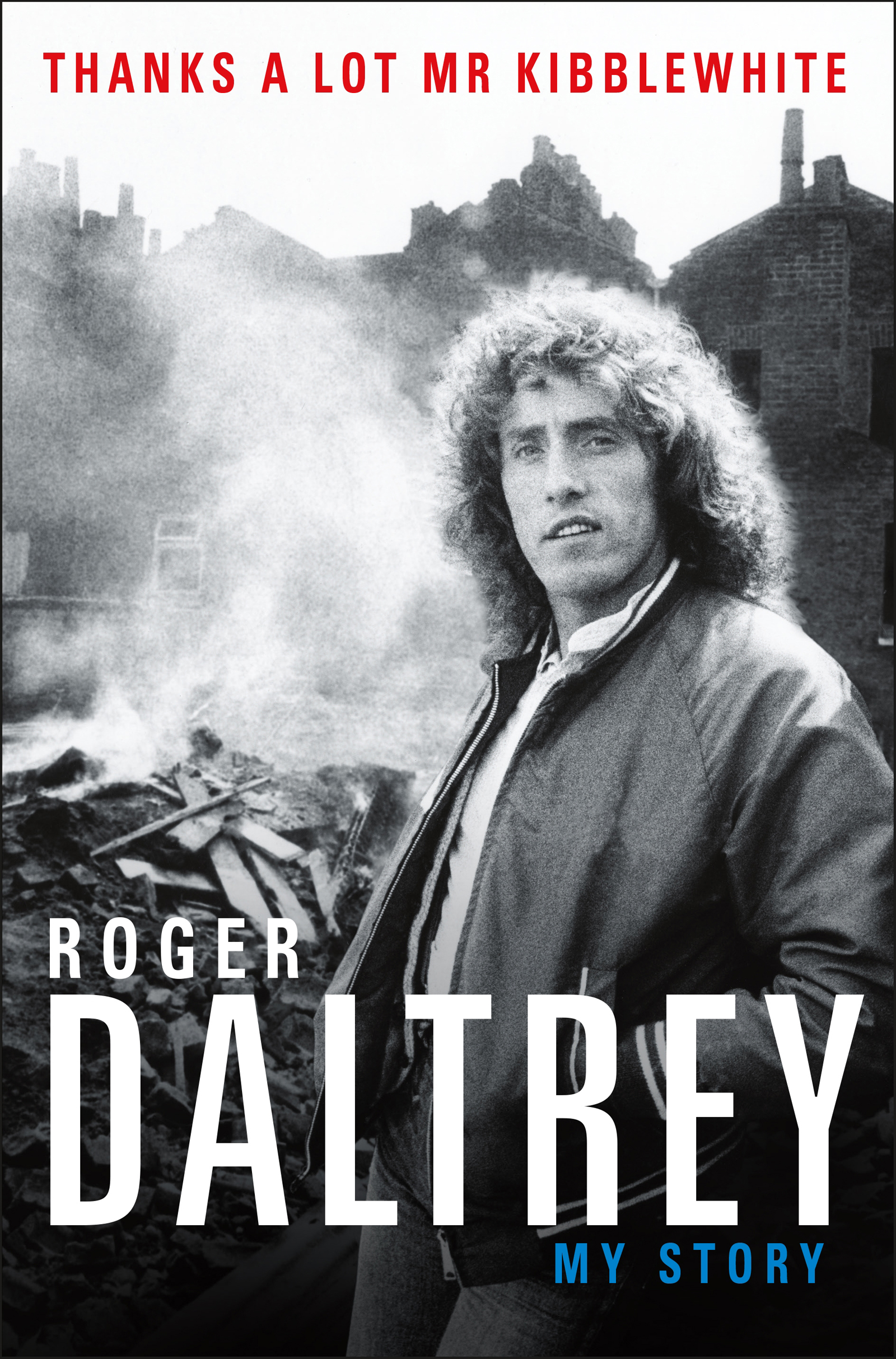

My thanks and acknowledgments go to the people who have helped me with the writing of this book.

To my wife, Heather, who has been the not so silent partner. She has advised, encouraged, and given perspective to me throughout my life.

To Bill Curbishley, Robert Rosenberg, and Jools Broom at Trinifold Management and to Calixte Stamp and Keith Altham for their help and support.

To Jane Howard, Nigel Hinton, Richard Evans, Matt Kent, and Jack Lyons for checking all the drafts.

To Chris Rule for the photo layout.

And, of course, a huge thank you to Matt Rudd.

To Jonny Geller at Curtis Brown and the teams at Blink Publishing and Henry Holt and Company.

And, it goes without saying, thanks to Pete, John, and Keith without whom this would have been a much shorter story.

On a muggy Florida night in March 2007, Pete and I walked out onto the stage at the Ford Amphitheatre in Tampa. For the ninth time that month, the seventy-ninth in the past nine months, the band started into I Cant Explain. I swung my mic straight out toward the audience, ready to go like always. Ready to hit that first line Got a feeling inside . But the mic weighed a ton. Out it went like a ships anchor. Whether it came back, I cant tell you. Everything went black.

The next thing I knew, I was backstage. The lights were swimming, concerned voices came and went. Pete was there, wanting to know what was wrong. And in the distance I could hear the din of twenty thousand disappointed fans.

For fifty years straight Id always made it. Id always turned up and performed. Hundreds of gigs. Thousands. Pubs, clubs, community centers, church halls, concert halls, stadiums, the Pyramid Stage, the Hollywood Bowl, the Super Bowl, Woodstock. When the lights came up, I was there. Front of stage. Ready to drive. But not that night. For the first time since Id picked up a microphone, aged twelve, and sang Elvis, I couldnt perform. As they bundled me into the back of an ambulance I was more disappointed than anyone that night. I listened to the sirens andanother new experienceI felt helpless.

In the days after, the doctors did a lot of poking and prodding, and eventually worked out that the salt levels in my body were way lower than they should have been. It seems obvious now but Id never worked it out. Every time we were on tour, two or three months in, Id get sick. Really, really sick. And now, after all these years, I find out the reason was simple. It was because of salt or the lack thereof. All that running around, all that sweating, it drained me. We were athletes, but wed never trained like athletes. Two, three hours of night in, night out, and wed think nothing of it. No warm-downs. No stretching. No vitamin supplements. Just a dressing room with alcohol in it. Because were a rock band, not a football team.

That wasnt the only thing I learned that week. A few days later, one of the many doctors walked in clutching a chest X-ray.

So, Mr. Daltrey, when did you break your back? he asked.

Politely, I pointed out that I hadnt.

Politely, he pointed out that I had. He had the evidence, right there on the X-rayone previously broken back, one not very careful owner.

Youd think Id have noticed when I did it, but Ive been in enough scrapes in my time. There is an element of luck to any rock and roll story, but the luck only comes with hard graft. When you fall down, you get up again. You just keep on going. Thats how it was at the beginning and its how it still is today.

I can think of three occasions when I might have broken my back. There was the time we were filming Im Free on Tommy in 1974. One minute, fifteen seconds in, youll see me being thrown into a somersault by an army bloke. It was an easy enough stunt, but I fell badly. I cant remember if I heard anything snap but it bloody hurt. And for the rest of the day we were shooting the opening of the song, the part where my character, Tommy Walker, falls through the glass. We did it outside first and then we went into the studio to mimic it on the blue screen. All afternoon we did that. Me, falling four or five feet onto a mat. And cut.

One more time, Roger. That was one of Ken Russells favorite catchphrases. He always liked to take his actors over the edge.

Are you sure we havent got it, Ken? I replied with my possibly broken back.

One more time, Roger.

Sure thing, Ken.

Or I could have done it on March 5, 2000, on my way to the Ultimate Rock Symphony gig at the Sydney Entertainment Centre. Paul Rodgers of Bad Company had called in sick so I was going to cover his songs as well. They sent a van early; I jumped in and I was warming up my voice on the way to the arena. Ive got this process where I hold my tongue with a towel in one hand and my chin with the other and I do these strange scales. It sounds mad and it looks mad, like Ive been possessed by a demon. Id like to think its a relatively tuneful demon, but its still not what you want to be doing when you have a car crash.

The woman joining the freeway had other ideas. She swerved into our lane with no warning. My driver managed to brake and we hit her side on. It wasnt too bad. I still had my tongue wrapped in a towel and we were all still alive. I didnt hear anything snap but it hurt like hell. When we finally arrived at the gig, an osteopath turned up and clicked everything back before I went onstage. I got through it on pure adrenaline, I suppose, but for the next three years I was in constant pain.

I think the most likely time was when I was at band camp, aged about nine or ten. Lets say 1953. I was the Boys Brigade company singer and I used to go up and down the beach on the sergeants shoulders belting out uplifting American marching songs at unsuspecting holidaymakers. I sang like a little angel.

The only problem was a boy called Reggie. Reggie was also in the Boys Brigade. He was this big kid. Im not kidding. He was a foot taller than me and two feet wider. He lived on Wendell Road in Shepherds Bush, which was only five minutes from where I lived on Percy Road, but that made a world of difference. There were certain families you didnt get on the wrong side of. There still are. Londons like that. And in Shepherds Bush, it was Reggies family. They were a rough family from a rough street, and, unfortunately, Reggiebig Reggiehad it in for me.

So there we were, at band camp, and because I was the little one I was being thrown up in the air in a blanket. Its the sort of thing kids used to do for entertainment before iPads were invented.

Reggie was the ringleader and, while Im fifteen feet up in the air, he shouts, Lets let go! I can still hear the bugger saying it now. Lets let go!

Of course, they all let go of the blanket. There was nothing I could do. I crashed to the ground and I was knocked out cold. There might have been a snap, but I was away with the fairies. Now, on the one hand, it meant band camp was ruined. I had to spend the rest of the day down the bloody hospital and the rest of the week stuck in a Boys Brigade tent in agony with what I now reckon was a broken back. On the other hand, I was sortedmy problems with Reggie had come to an end. As I lay there on the ground unconscious, he thought hed killed me.