SPRING

CONTENTS

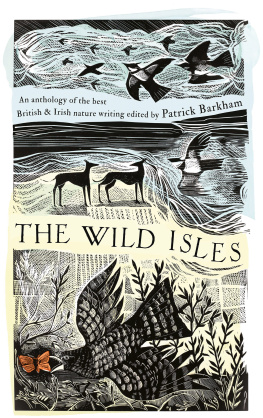

INTRODUCTION

I t is a moment of quickening, of rebirth. The old, lovely story: life surging back, despite everything, once again. However spring finds you birdsong, blossom or spawn it is a signal: the earth turning its ancient face back to the sun.

For me its snowdrops, fat black buds on the ash trees and the blackbirds first song that tell me springs arrived. I live in a city, as more and more of us do these days, and so the signs seem even more precious, even easier to miss. Each year I seek them out, anxiously, ardently: each year I feel the same atavistic joy as the green world starts to grow and the birds breed.

On these temperate isles we have been bound to the seasons since time immemorial, dependent on the circling year and its ancient pattern of growth and senescence. That our homes are warm and bright all year round, that we can eat what we want whenever we like, are recent developments in evolutionary terms: no surprise, then, that we have not lost, in a few generations, our deep connection to the changing year. Springs quickening still quickens us, whether villager or urbanite, farmer or commuter. Its in our bones.

And the seasons roll through our literature, too, budding, blossoming, fruiting and dying back. Think of it: the lazy summer days and golden harvests, the misty autumn walks and frozen fields in winter, and all the hopeful romance of spring. Sometimes, as with Chaucers Aprill shoures, the seasons are a way to set the scene; sometimes they are the subject-matter itself but theres magic in the way a three hundred-year-old account of birdsong, say, can collapse time utterly, granting us a moment of real communion with the past.

Although that sense of changelessness is now, sadly, an illusion. Our busyness, our industry, have altered the worlds climate, shifting the timing of many natural phenomena and interfering in natural events that have been happening for millennia. We are also witnessing a widespread, sudden decline in wildlife on these islands, which is changing our experience of all four seasons. And so it is more and more important today that we engage with nature physically, intellectually and emotionally, rather than allow ourselves to disconnect; that we witness rather than turn away, and celebrate rather than neglect.

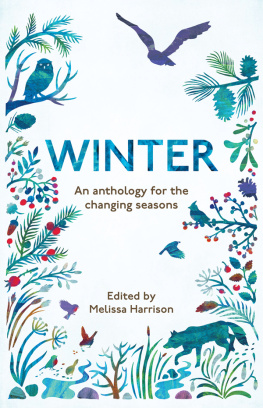

This book, the first in a new series from The Wildlife Trusts, is an attempt to do just that. A collection of writing both classic and modern, and from all corners of the country, it mixes prose and poetry dating back a thousand years to tell the story of springs yearly progress across these islands, and remind us of all we have not yet lost. Most excitingly, I think, these four books feature new writing by members of the general public as well as by established authors, adding up to a fittingly diverse range of voices that sing out the seasons joy.

Nothing is so beautiful as Spring, wrote Gerard Manley Hopkins in 1877. He was right.

Melissa Harrison, Spring 2016

I n the Northwest Highlands of Scotland, wildlife and landscape are as defined by light and wind as by geology, vegetation and people, and by the yearning for brighter days as the long winter months pass.

Here, on a small croft by the sea, winters are deep and dark, stormy, cold and fierce. There is no easy way out of winter. Its cold, hard grip is periodically loosened when strong, warm, westerly winds blow in from the Atlantic and then our mountains, snow-clad and proud, lose their glistening blankets. Snowmelt waters unite with the tepid storm rains and churn down towards the sea, noisily lighting up the frothing burns and flooding lochans. Fierce squalls batter and pound, whipping up bird, beast, tree, leaf and sea, while rushing snatches of cloud, shower, rainbow and sunbeam paint our hills and croft fields in kaleidoscopic colours. When the winds pause again, hazy, moisture-laden airs diffuse sunlight through pale-lemon and grey veils, and smoothe waves into quicksilver and opal slickness. In these brief remissions of citrine lull and cobweb-light breezes, a sense of expectation grows, along with a discernible shifting of the light and subtle extension of the days. Winter is ending.

As the sun sinks low each late-winter day, the ground, bleached pale, reflects the dying light and for a few short breaths turns pink and purple, as though the earth itself knows that spring is coming. Growing midday brightness is flanked by this surreptitious, dwindling luminosity, when hill, sky and sea merge in opaque diffuseness. Making the most of these tranquil interludes, birds call out, chattering and gossiping, organising each other and arranging feathers in accordance with the latest fashions. Along the shore, waves are viridian, hanging low and large, thumping slowly down in champagne froth and lacy spray. The otters play through the foam and surf with such unfettered joy that we know, even in moments of doubt, that spring is on its way.

In February such gentle days are brief. Winds soon return: Its not time yet! they shout, not time yet for spring! No sweet murmurations here: birds are hurled about and, with skill and heart-bursting endeavour, they soar up only to be tossed across the fields like old, dry leaves.

But slowly, steadily, light grows in strength, and there comes a day when it finds the nooks and crannies of the fields, sneaking in between tree trunks and delving into shadowy recesses in byre and croft house. And suddenly a golden glow filters deep through retinas into minds, so bodies shift, heads lift, hearts beat more swiftly, lungs fill, change is sensed.

Soon longer, mad March days arrive with lofty bright blueness and energetic risings of thin white clouds. White-topped, sparkling waves call out to one another, and in their headlong rush to the shore whip up fizzy delights, cappuccino foam. In the dunes, machair grasses nod and dance, trying to catch the breezes. Above the whirling of air and waves comes the sound of joyous voices, euphoric, unrestrained: the first skylarks are pitching lungs, hearts and minds in unison with the sea.

Other pre-equinoctial days are not so effervescent and succumb to biting cold, icy crystals and glistening beads of snow and hail. There is a lowness to the landscape then: across the fields, the tufted grasses are still bleached blonde and sodden, heathers gnarled and frizzled to burnt umber and remnants of bronze bracken fronds are scattered here and there. And yet this squishy, pale mat of grass is gradually being absorbed back into the slowly warming earth, its job of protecting soil, fungi, bacteria, worms and hibernating insect larvae during winter now done. Here and there bright green shards appear like livid swords, piercing the mesh and tangle. In this still-dampened-down world, little pathways are visible: Lilliputian highways and low-ways for secret furry scurryings; neat spiralled entrances to dew-covered, spider-webbed dens, some only a fingers width, thresholds to the undergrass byways of voles, shrews and mice, safe from raptor camera-lens vision.

Above, another highway: gulls and terns gather and bustle, shouting their greetings in the early morning airs as they follow the same route along the river as it meanders through the croft fields down to the sea, like a school run. They gather on the glistening sands or bouncing waves, shrieking and clamouring, organising last years youngsters in frowzy brown and grey groups. And when the business is done, the register complete, up they soar to follow other indiscernible airy trails.

Next page