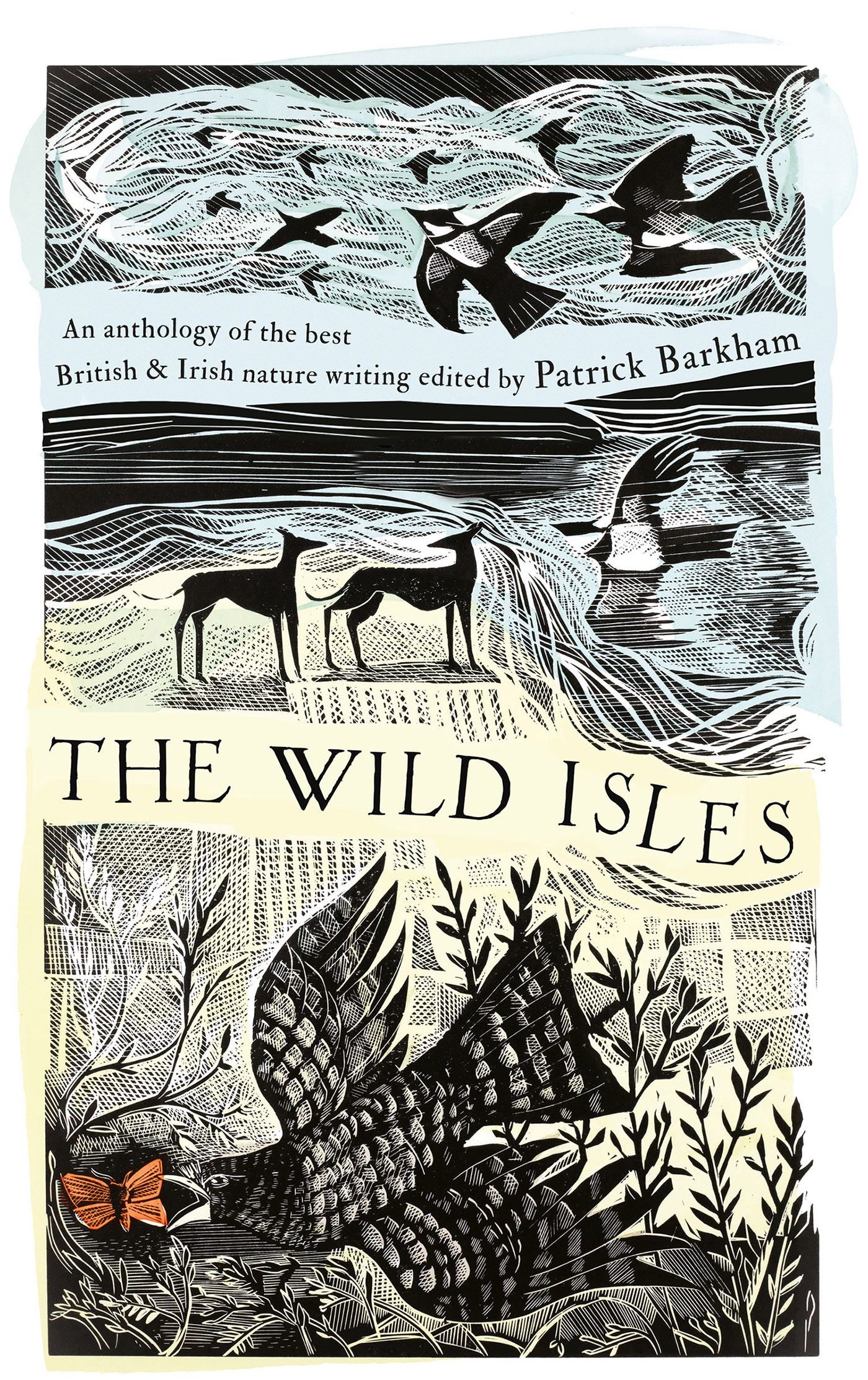

THE WILD ISLES

THE

WILD

ISLES

An anthology of the best

British & Irish nature writing

Edited by

Patrick Barkham

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

First published in the UK in 2021 by Head of Zeus Ltd

An Apollo book

In the compilation and introductory material Patrick Barkham, 2021

The moral right of Patrick Barkham to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of the contributing authors of this anthology to be identified as such is asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The list of individual titles and respective copyrights to be found on constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

All excerpts have been reproduced according to the styles found in the original works. As a result, some spellings and accents used can vary throughout this anthology.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN (HB) 9781789541403

ISBN (E) 9781789541397

Chapter-opening linocuts Sarah Price

Head of Zeus Ltd

First Floor East

58 Hardwick Street

London EC R RG

WWW . HEADOFZEUS . COM

THE WILD ISLES

CONTENTS

It is autumn and spiders silk stretches across dewy paths like tape at a finish line. The race to grow, that burgeoning rush of spring and summer, is at an end. The skies have emptied of swifts, the sunlight softens and all is quiet. A mew like a distressed cat falls from the stillness high above the industrial estate next to my home: a young buzzard, fledged and soaring, still asks its parents for food. In the garden, my children and I collect conkers, cool to touch, encased in cream memory foam, and decorated with whorls that resemble a chestnut map of the world. On the walk to school a giant puffball, bridal white and pregnant with possibility, lies on the first fallen leaves, kicked loose by a passing teenager.

We live in a busy, suburban place in lowland Britain, one of the most nature-depleted countries on the planet, in a geological era defined by the destructive dominance of human beings. And yet other species continue to make their lives all around us and to change our own. We still reside alongside plants, animals and fungi which keep us alive and well helping us breathe and providing us with food, or pollinating and fertilizing what we grow. If we look up, or down, or pause and take notice with any of our senses, these living things give us a sense of companionship and wonder.

Writing about natural landscapes and wild species is flourishing like never before. Nature writing has been given pleasing green space in many bookshops. The lives of plants and animals intrude more visibly into novels, childrens books, poetry, screenplays, blogs, social media and films. Nature seems to be moving through the work of visual artists, sculptures and musicians with a new dynamism. This is no coincidence.

As we live in a world that is more technological than ever, with more of us collected in cities than ever before, we have been liberated from the back-breaking physical labour required to work the land that defined thousands of years of our evolution. But we also find ourselves alienated from the non-human world, and craving connection with it. We find solace and succour, and mental and physical good health from time in nature. An increasing number of us seek to bond with nature vicariously too, via culture and reading about the wild world. The best writing nourishes us in many different ways: it may soothe us, entertain us, inspire us, anger us or encourage us to spend more time among non-human life, as admirers or custodians.

I hope you, like me, will find pleasure, wonder, refreshment, motivation and perhaps a new way of looking at the world from the British and Irish nature writing I have collected in this volume. Nature writing is a complicated term and I should explain how I have chosen to define it. I also want to briefly summarize its history in Britain. Finally, Ill reveal how I chose this selection. Dear reader, I dont want to give too much away yet but it involved many a genuinely exciting hour in the British Library.

Writers today mostly dont particularly like the term nature writing. We are nature, so all writing is nature writing. Like most of my nature writing peers, I also say Im just a writer. Some of my work is about our relationship with other species or landscapes where other species live. Nature writing is undoubtedly a piece of marketing shorthand, a publishing genre that helps books find a home in a bookshop. However, I think it is a valid concept; a useful banner to march under, as its leading proponent today, Robert Macfarlane, put it back in 2003 when he began to map this flourishing. I define nature writing as any writing that considers other species or non-human places and our relationship with them. Unlike a field-guide, for instance, which provides in plain text some facts about the appearance or habits of a flower or a bird, nature writing usually possesses a lyrical or poetic quality, romance as well as science.

For the purposes of this one modest volume, Ive had to tighten that definition. I take the birth of British nature writing to be 1789, when Gilbert Whites The Natural History of Selborne was published. Never out of print, the Hampshire curates close observations of the changing seasons and secret lives of plants and animals was an early kind of ecology. White has inspired and informed subsequent generations in many different ways. His work reached scientists, modernists and artists, from Charles Darwin to Virginia Woolf. I decided I could not offer an exhaustive encyclopedia of historic works, and so Gilbert White feels like a good place to begin what is a brief introductory tour of modern British and Irish nature writing.

Of course there is plenty of writing about nature before 1789. When I interviewed the writer and poet Kathleen Jamie, she said that all writing before 1900 was nature writing. When we lived more closely with the land, it seeped into our culture rather more. There is a wealth of poetical observation about the natural world to be found everywhere from Anglo-Saxon poetry to William Shakespeare. Many earlier non-fiction works about nature were by sportsmen-authors, who wrote with varying degrees of accuracy and flair about the species they hunted. George Turbervilles The Noble Art of Venerie or Hunting , first published in 1575, features a panoply of creatures that lived, and died, solely for our gratification. These hunter-naturalists share with nature writers the quality of taking notice. Plenty of lyrical nature writers from more recent times have been predators too. Gavin Maxwells first book was a brutal account of hunting basking sharks off the west coast of Scotland.

I see modern nature writing in Britain and Ireland rising from three groups of people: from these sportsmen authors who closely observed the natural world to understand their quarry; from the first scientific naturalists who wanted to explore how the natural world functioned and how it could best be classified; and from the Romantics who defined a radically new relationship with nature as a place for self-discovery, personal growth, awe, appreciation and wonder. The Romantic poets, particularly William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and later Romantics writing in response to fears about the direction of the agricultural and industrial revolutions, are the most significant shapers of modern nature writing. I havent included poetry in this volume because that would make it an unreadably epic enterprise (and I am totally unqualified to assess the merits of poetry) but I have included the prose of Dorothy Wordsworth and John Clare, whose reappraisal in the twentieth century inspired new British nature writing.