This collection contains what I hope are the most compelling nature stories from two decades of writing for the Guardian. They are mostly what I love best: venturing into the world with eyes wide and mind open and writing honestly about other people and their relationships with other species. These are adventures and discoveries that became stories about wild and not-so-wild places, people and other species.

We are often almost unknowingly drawn to a place that feels like home. In 1998, when the dotcom boom was firing up in warehouses between Westminster and the City of London, I took a shuddery old lift to the converted attic of a tatty commercial building in Clerkenwell for a job interview. Beneath high, whitewashed rafters was an airy space filled with pot plants and beige boxy Apple Macintosh computers that were tapped by self-assured, serious young people in casual clothing. This was the home of the Guardians new website, soon to be rebranded Guardian Unlimited.

I belonged to an extremely lucky generation, graduating during the burgeoning optimism of the first years of the New Labour government, when old newspapers were looking for cheap young graduates to staff their clumsy forays into the new media of the World Wide Web. Id wrangled a bit of work experience at ITNs website and the Financial Times website but as soon as I answered a job ad (paid entry-level opportunities in the media! Ah, those were the days!) for a writer/researcher and stepped into the Guardians Ray Street office, I knew I wanted to work there. My mum had read the Manchester Guardian as a kid; Id grown up in virtually the only Guardian-reading household in our rural village; the Guardian was home.

After two years working on the website, I landed the job of the Guardians sole Australia correspondent and left the Ray Street office. This sounds glamorous, and it was, but in the realm of foreign correspondency it was the most junior role, in a part of the world that narrow-minded London editors deemed relatively unimportant. My job was to supply a bit of light relief: stories about the Olympics, which began just as I arrived, and other quirky, inconsequential reads. My first hit story was about a prehistoric stick insect dubbed the walking sausage, which had been discovered on Lord Howe Island.

A few months after I arrived in Australia, I wrote about the northern hairy-nosed wombat, and how this endangered species was threatened with extinction by the destruction of its rainforest habitat. It was the first story I really cared about. I felt so sorry for the wombat, and deep empathy for the sorrows of its human champions. At a trivial level, the wombat was cute. At a portentous level, our relationship with the planet and its species simply seemed like the most important subject. But writing about all this also felt like home.

It was familiar to me because I had grown up in the countryside, the child of parents who cared deeply about the natural environment. My parents did the Good Life thing in the 1970s and we were raised on an acre-and-a-half of land with goats, rabbits and plentiful home-grown vegetables. Mum was a geographer, and passionate about natural landscapes. Dad nursed a profound emotional need to be close to wildlife and taught environmental science at the University of East Anglia in Norwich. With the keen ear of a child, I absorbed their discussions about the destruction of hedgerows, the hole in the ozone layer, and the need for people to live more sustainably.

Siding with the planet is to side with the underdog, and this motivated much of my journalism. I didnt write that much about wildlife or environmental issues at first, although after two years in Australia I felt I had covered every possible wryly amusing story about wacky animal happenings, from koalas invading the suburbs of Adelaide to killer jellyfish. The most significant issue I reported on during my time in Australia was the plight of refugees who were intercepted in boats seeking the safety of the lucky country and dispatched to offshore processing which meant indefinite detention on the dysfunctional tropical island of Nauru. My big dispatch from Nauru was published on the morning of 11 September 2001 as the twin towers in the United States crumbled. The refugees did not get the attention they deserved.

I dont want to sound grand, because I wasnt: I was a young person slowly learning how to be a competent journalist. Before I returned to London in 2002 I wrote a dispatch from the idyllic South Pacific island nation of Tuvalu, which was and still is threatened with inundation as sea levels rise because of human-made global heating. This is the earliest piece to appear in this collection and it remains deeply pertinent twenty years on. Over the next decade I became a general reporter and then a feature writer (writing longer stories), which meant I wrote about all kinds of subjects. I spent two years at The Times and was dispatched to report on the Iraq War. Even though I was based in probably the safest place for a war correspondent a hospital ship I discovered that I was too much of a coward to do war reporting. Ive never had the toughness to be an investigative journalist either. In 2004 a reporters job was advertised at the Guardian and I was able to return to my journalistic home. Here, I reported on the plight of Gypsies and Travellers in this country but I also morphed into one of those embarrassing yoof correspondents, reporting from Glastonbury or writing amusing fluff about being a metrosexual or wearing onesies (my personal favourite).

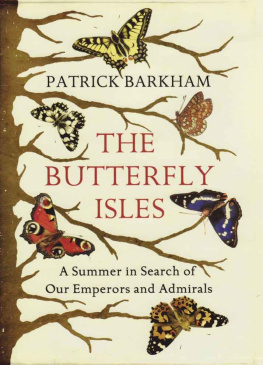

There is not much I havent written about over twenty Guardian years, from business stories to celebrity interviews to diaries to obituaries more than 1.6 million printed words and almost another million for the website. A lot of these were deeply inconsequential or not arranged in a particularly alluring order. But whenever I turned to report on an animal or an environmental issue I felt a deep sense of kinship with it. In 2009 I wrote a book about butterflies, The Butterfly Isles. Reconnecting with this childhood passion made me more determined to spend more of my time telling the many miraculous stories about other species and our relationships with them. When I half-heartedly tried to leave the Guardian in 2013 they were offering voluntary redundancy and I was tempted to become a full-time book-writer a particularly kind editor asked me what my dream role might be. My answer was to report on wildlife all the time. He gave me a preposterous job title, Natural History Writer, and, for the last eight years, working part-time at the Guardian while also writing books, this is what Ive done.

As well as writing an indecent amount about butterflies, Ive discovered that the natural world supplies an inexhaustible fund of funny and fascinating revelations, even when many of these stories also bring out a sobering indictment of humankinds myopia, chronic short-termism or greed. Ive never been a polemical writer like my brilliant colleague George Monbiot; Ive never had a column on the opinion pages where I formulate ferocious arguments about the undoubted stupidity of our species authoring of a planetary overheating and the sixth great epoch of extinction. Temperamentally, I just cant do it. When I argue about things I get all ranty and feel ill.