How I learned to love little brown jobs

B ehind the marram grass were twisted old pines and hollows that smelt of hot thyme. The warm ground was pebble-dashed with dry rabbit droppings. Holidaymakers splashed about on the beach; birders hunched in the hides. Only my dad and I crossed the empty no-mans-land of the rolling sand dunes, performing an odd, trotting dance, tracing random circles as we followed invisible darts of silver.

I was eight. For most of us, butterflies are bound up with childhood. Many of our earliest and most vivid memories of a garden, a park or flower will feature a butterfly and, perhaps, our pudgy hand trying to close around it. My love of butterflies began not with a blaze of colour but with a small brown job. Thats what my mum called the common plodders of the butterfly world that would scarcely divert your gaze as they bimbled past. Meadow Browns or Hedge Browns or Wall Browns. Mostly brown and fairly dull.

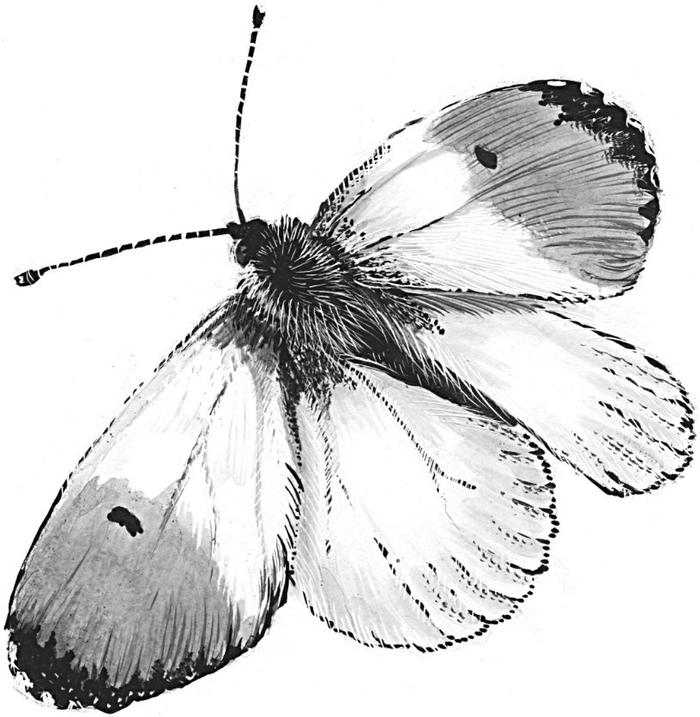

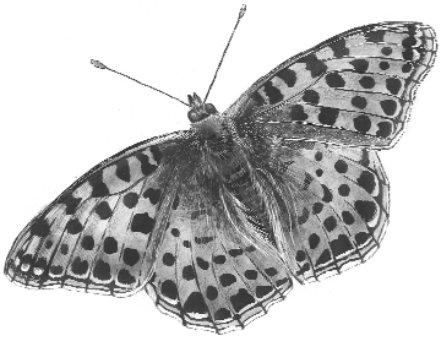

This particular brown job was different: the Brown Argus. It was smaller, sharper and brighter than most butterflies with brown in their name. An arrow of silver grey in flight, its open wings were deep, dark chocolate with a border of dabs of orange. It was not exactly rare but was hard to find in East Anglia, where meadows had been ploughed into huge butterfly-unfriendly prairie fields during decades of intensive arable farming. It had not been recorded along this part of the coast in recent years. This may have been because no one had been looking, but it still gave us a mission: if we could find one, it would be a new sighting. Dad, I felt, could then Tell Someone. Who, it was not quite clear, but I had faith that he would.

We were on our summer holiday at Holme Dunes nature reserve. During the austere portion of the 1980s, the era of inner-city riots and the miners strike, my mum, dad, sister and I would spend two weeks of the summer in a small damp flat at the end of a bumpy track on the corner of the coast where north Norfolk turns into The Wash.

Every morning, mum would march us through spikes of marram to the beach, where she would defiantly sunbathe behind a windbreak, whatever the weather, and my sister and I would dig in the sand for hours and hours. In the mornings and evenings, borrowing mums heavy binoculars which banged against my chest, I would follow my dad down the paths to the wooden hides built overlooking shallow pools on the marshes and we would watch strutting green-shanks and avocets sweeping their bills methodically through the water. There is a photograph of Dad and me standing on the patio of the Firs, the rambling, isolated Edwardian house on Holme Dunes, which was divided into a flat for the nature reserve warden, a flat for holidaymakers and various dusty rooms filled with old signs and detritus from beach and reserve. Binoculars to his eyes, Dad stands there watching a heron on the channel close to the house. Im at his side in little shorts and a mini-me pose, following my dads line of vision, my mums smaller binoculars pressed to my eyes.

The child of a broken home back when divorce was almost a social disgrace, my dad had found a solitary peace as a boy by running wild in the lanes and meadows of rural Somerset. He hunted out birds nests in hedges and taught himself how to identify trees and grasses and flowers. As a young man, he lived in a caravan in the woods for weeks on end and studied wild daffodils. His career, inevitably, was rooted in the natural world he taught environmental science to university students and, as a grown man, he spent his spare time seeking out wildlife and wild places. He often preferred to be alone.

In my eyes, Dad had the power to interpret every tremble of a leaf and every distant bird call in the countryside. His superpowers deserted him on butterflies, however. This particular year, on holiday, he created a little project for himself, which he seemed happy to share. He had a hunch that Holme was the perfect habitat for the Brown Argus. They were listed in old books as flying in this bit of north Norfolk but Dad was not sure when they were last seen here. It could have been decades ago. So we set out one hot afternoon on our first ever butterfly mission.

It was written in the stars that I would become a birdwatcher. Holme, where we holidayed every summer, was one of the best spots in East Anglia for rare birds. Every year, exotic species would be blown far off course and end up lodged in a sea buckthorn bush on the dunes. Hundreds of birders from all around the country would descend on the reserve with their cameras and tripods. Here was a passion tailor-made for a small boy who loved nature like his father. Nature, but drama as well: scarcity, rarity, unpredictability and the boundless obsessive possibilities in creating lists and ticking things off, and trading gadgets, rare sightings and stories with the wider community of twitchers. My dad had a modest interest in football, took me to a couple of matches and I duly became obsessed with football. My dad had a grand passion for wildlife and took me bird-watching but, somehow, an obsession did not follow. I was always happy to go. I enjoyed peering at birds through binoculars. I liked the creosote pong of the hides, the lonely peen of waders and the empty sweep of marsh rising gently towards Holme church and village beyond. But nothing happened. In some receptacle of my brain, some small cell, the obsessive passionate cell, refused to twitch.

It took a small brown job to make that cell come alive. That first afternoon, hunting the Brown Argus, I could feel the heat radiating off the dunes onto my bare legs as I walked solemnly in my dads footsteps, holding a blue biro and a piece of paper fixed to my pride and joy a clipboard to record everything we saw.

I kept a careful tally of each butterfly: I, II, III and we quickly clocked up some browns: the bland and slightly floppy Meadow Brown and the brighter, bustling Hedge Brown, also known as the Gatekeeper, a name which suits its friendly, busybody personality. There were dozens of Small Tortoiseshells familiar to anyone like us who had a garden at home and a few Small Heaths. I soon saw it was a bit unfair to call the Wall a brown job because they were as elegant as Tortoiseshells, if less charismatic. There was a brilliant carroty flash as a Small Copper settled and opened its wings in the sunshine and the fine, bright midsummer hue of the Common Blue. Then we spied movement: a grey arrow flying low over clumps of marram. For a beginner, it is not easy to definitively identify a Brown Argus. The topside of its wings may be a striking dark brown but, in flight, thanks to its speed and the black and white dots on its beige underside, it looks grey, or silver, and uncannily like a female Common Blue.